Strategizing the European Union

The European Union has a meager track record of anticipating and containing external threats. The bloc’s 2016 Global Strategy is an attempt to rectify this situation by devising an integrated security approach that avoids the extremes of isolationism and interventionism.

In a nutshell

- Early efforts at formulating EU security strategy had few practical results

- The 2007 Lisbon Treaty encourages closer defense ties, even without consensus

- The EU’s 2016 strategy aims to turn the bloc into a global security player by gradual steps

The European Union is facing enormous security challenges. Meeting them requires a strategic approach rather than an operational one. In the formal sense, the EU does have its 2016 Global Strategy, but as always with such documents, everything depends on its practical implementation.

To gauge how Europe might fare in today’s murky and complicated security environment, it may help to step back and examine how the EU’s security policies and doctrine originated and evolved. On this path, one can distinguish three milestones: 1) the bloc’s “pre-strategic” phase before its first security strategy was announced in 2003; 2) the Lisbon Treaty as an impulse and framework for updating security strategy; and 3) the 2016 Global Strategy as an attempt to devise and implement a world-scale grand strategy.

Before 2003

From the moment of its founding in the 1992 Maastricht Treaty, the EU had a Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP), which was treated as the Union’s central pillar via intergovernmental coordination of the member states. Its military arm was the Western European Union (WEU), which could be directed to perform security tasks by the EU. For this reason, the EU had no need to formulate a strategy for itself, since this responsibility could be “outsourced” to the WEU.

The 1997 Amsterdam Treaty introduced a High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy, while the 2001 Nice Treaty removed the WEU and its military responsibilities from the EU’s purview. At this point, the bloc had both the need and the opportunity to formulate its own strategy.

The European Security Strategy was more a political manifesto or a statement of good intentions.

Javier Solana, the high commissioner at that time and a former secretary-general of NATO, drafted the EU’s first security strategy, which was approved by the European Council on Dec. 12-13, 2003. This document was an important step toward consolidating the Union’s external policies.

The point of departure for the 2003 European Security Strategy (ESS) was to define the EU as entity with global security responsibilities and ambitions. The document identifies six threats listed below.

Facts & figures

Six key threats

Large-scale aggression: Improbable against member states. Instead, Europe faces threats that are more diverse, less visible and less predictable

Terrorism: A growing strategic threat to all of Europe. Global in scale and linked to religious extremism

Proliferation of weapons of mass destruction: Potentially the greatest security threat, especially in combination with the development of ballistic missile technology and terrorism

Regional conflicts: Direct and indirect threats, especially from the Middle East

State failure: Consequences of bad governance (corruption, abuse of power, weak institutions, lack of accountability) and civil conflicts. These add to regional instability

Organized crime: Europe is a prime target for cross-border criminal activity, often associated with failed states

European Security Strategy: 2003

The main strategic objectives of the 2003 ESS were to counter threats, by preventive action if necessary; enhance security in the immediate neighborhood by supporting transformation in countries bordering on the EU, and strengthen the international order by buttressing the rules-based, multilateral system. To achieve these goals, it was assumed that the EU would have to be active and cohesive, develop new capabilities, and closely cooperate with other international actors. Worth noting is that this document devotes little attention to transatlantic cooperation.

The EU’s strategic practice did not improve much, if at all, after 2003. The ESS was a political manifesto or statement of good intentions, without any practical means of achieving them. This was its greatest weakness. Member states were simply not interested in “doing” security policy within the EU framework.

Several serious tests – especially from Russian neo-imperialism – showed the EU and NATO coming up short.

Meanwhile, the security environment was becoming more challenging. Several serious tests – especially from Russian neo-imperialism – showed the EU and NATO coming up short. Particularly jarring were the Russian-Georgian war of 2008 and the gas crisis in January 2009. These made evident the glaring need for enhanced EU security capabilities and a revised strategy. Another reason for revisiting this issue was the EU’s acceptance of the Lisbon Treaty in 2007.

Treaty of Lisbon: 2007

The EU as described in the Treaty of Lisbon is a very different animal from other international organizations, such as NATO, the United Nations or the Organization for Security in Co-Operation in Europe (OSCE). It is a legal entity with powers vested in it by the member states. In security matters, however, and especially in matters of defense, it is a classic international organization that relies on an intergovernmental (rather than unified) decision-making procedure.

As a result, the EU’s security and foreign policy continued to be decided on a unanimous basis (according to the principle of consensus). That reduces the EU to the status of a potential, rather than a real, strategic player. It is sometimes able to make tough decisions on important issues, and sometimes incapable of reaching any decision on minor issues.

The scope of the CFSP covers the full spectrum of external relations and security, including collective self-defense. Its operational framework includes disarmament, humanitarian and rescue missions, military advisory services and assistance, conflict prevention and peacekeeping, quick-reaction combat missions in a crisis, and stabilization missions after conflict resolution.

The Lisbon Treaty’s so-called solidarity clause is not quite the same as a system of collective defense.

An important element of EU security is the Lisbon Treaty’s so-called solidarity clause. It states that the Union and its members must “act jointly in a spirit of solidarity” if a member state suffers a terrorist attack or natural disaster. This is not quite the same as a system of collective defense. However, the treaty does anticipate such a system by calling for “the progressive framing of a common Union defense policy” that “will lead to a common defense, when the European Council, acting unanimously, so decides.”

In the absence of consensus, the Lisbon Treaty allows a smaller number of member states (at least nine) to begin closer defense cooperation. Countries whose military capabilities meet more exacting requirements and have made bigger defense commitments can also begin “Permanent Structured Cooperation” (PESCO), a concept first formulated under the European Defence Initiative (2003).

These elements, together with lessons drawn from the transformed strategic situation after Russia began an asymmetric, hybrid war of aggression against Ukraine, formed the building blocks for a new EU security strategy that was adopted in 2016.

EU Global Strategy: 2016

According to this four-chapter document, the EU’s security strategy tries to balance two approaches, realism and liberalism, which find expression as interests and values, respectively. The EU’s strategic mission is to ensure that its citizens and member states enjoy the condition necessary to realize their basic interests and most important common values.

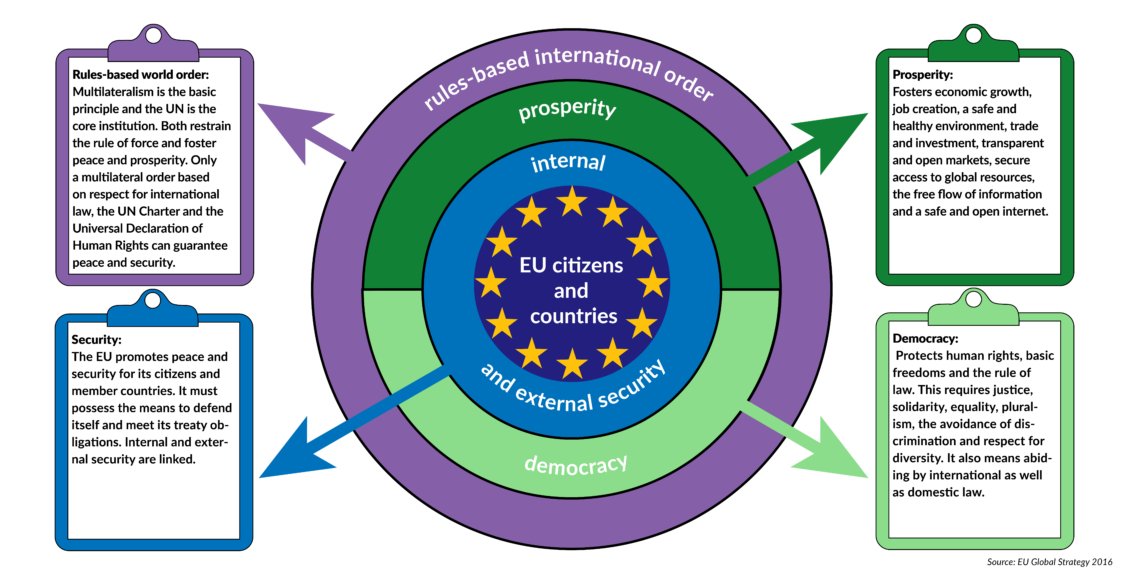

In the most general terms, this can be presented as a series of layers or buffers wrapped around the EU countries and its citizens. The innermost layer concerns the most elementary matters of survival, vital interests such as peace and security. Next is prosperity and democracy, which determine the quality of life. The outermost layer is the rules-based international order that surrounds the EU.

The golden mean of this strategy can be found the concept of “principled pragmatism,” which should govern the EU’s conduct in foreign relations. This means following a clear set of rules, based on a realistic evaluation of the external environment and on idealistic aspirations to help shape a better world. Europe’s path should steer clear of isolationism and primitive interventionism alike. Given the complex nature of contemporary conflicts and crises, the security strategy proposes a “comprehensive approach” spanning multiple dimensions, levels, time frames and partners (multilateralism).

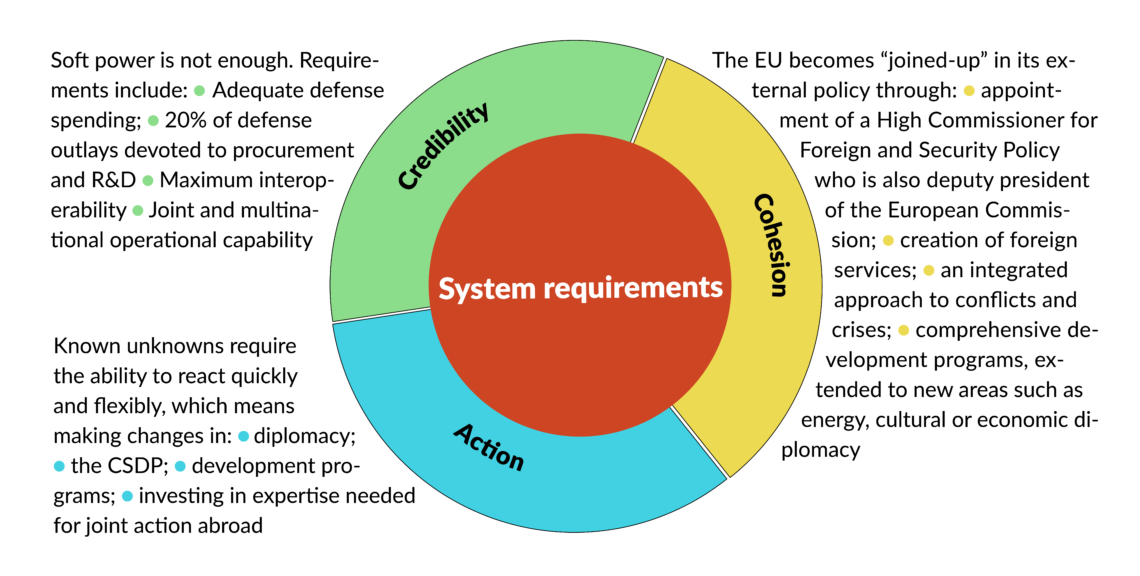

To achieve its aims, the EU must build a security system that is credible, active (or reactive) and cohesive. These requirements are illustrated in Figure 2 below.

The adoption of the new strategy revived interest in common security and defense policy at the EU’s executive level – the European Commission and the European Council – and in the European Parliament as well. These activities may have practical consequences in the future.

The EU Global Strategy is to be implemented in three dimensions: political, economic and international. The political dimension encompasses security and defense matters supervised by the EU High Representative; economics will be covered by a European defense plan executed by the European Commission; and the international aspect will be pursued by EU member states and institutions in cooperation with NATO.

Special attention should be paid to how the EU sets its so-called “level of ambitions” for security and defense. These comprise three tasks: a) reacting to external conflicts and crises; b) building partners’ capabilities; and c) defending the EU and its citizens. A second important sphere of activity is the European Defence Fund, which includes two separate but complementary financial channels (“windows”) to fund R&D projects on the Union level and expand military capabilities in cooperation with the defense industries of member countries.

Facts & figures

Figure 2: The EU as a security system

One practical measure that has resulted from implementing the Global Strategy has been the creation of an operational headquarters as part of the EU military staff, the Military Planning and Conduct Capability (MPCC). On the strategic level, the new entity will be responsible for operational and force-development planning. It will also coordinate military missions that do not require an executive mandate (generally, this would include training, advisory, humanitarian and other support missions).

Other important steps were preparations to implement Permanent Structured Cooperation (PESCO) between major European militaries, the introduction of a Coordinated Annual Review on Defence (CARD) for EU countries and regular meetings of member country defense ministers.

Strategic scenarios

In terms of intentions and plans, this is all well and good. The EU has clearly begun to act, and the will is evident to turn the EU into a well-organized strategic player. The question is whether these efforts will prove effective.

In June 2017, in a follow-up to the European Commission’s “White Paper on the Future of Europe,” two vice-presidents of the European Commission, Frederica Mogherini and Jyrki Katainen, published a “Reflection Paper on the Future of European Defence.” The paper contained three scenarios for building a European Security and Defence Union over the next decade. Depending on the political will of the member states, these scenarios would be:

- Security and defense cooperation – continuation of current policies, including ad hoc cooperation between member countries depending on the needs and situation, and with a minimal role for Union-level structures

- Shared security and defense – partial transfer of some competencies from member states to the Union level, especially for nonmilitary threats (terrorism, cyberattacks). Defense cooperation would become planned and systematic, rather than ad hoc

- Common defense and security – closer cooperation and integration of European militaries, synchronized defense planning, the formation of multinational combat units in a state of high operational readiness, complementing NATO in accomplishing defense tasks

Truth be told, the options listed above are really logical stages in the process of building a European Security and Defence Union. All three merge together into a single favorable mega-scenario.

But one should also consider the possibility of a less favorable scenario, in which it proves impossible to achieve consensus. This would leave the EU split into various circles of defense cooperation, each moving at a different speed and dealing with a different aspect. There would be a clear divide between a closely integrated core and a loosely affiliated periphery.

A multi-speed EU in defense would create a strange political and strategic hybrid. One could assume that even under conditions in which the various subgroupings enjoyed complete autonomy and conflicting procedures, it would be possible to work out mechanisms to secure a minimal level of defense cooperation. This security architecture would resemble the structure of an atom: a hard nucleus and floating electrons, held in orbit by their attraction to the core, but pulled away by their desire for independence. This would result in a scenario of imbalanced security and defense, containing elements of integration and disintegration.

This sort of EU might not survive for long, collapsing sooner or later into its constituent parts. That would be the scenario of a European security collapse. Advocacy of mirage-like strategic alternatives to European integration, such as the Intermarium or Three Seas Initiative, could inadvertently contribute to such a scenario, as would counting on the United States to support such initiatives.

The EU has made a long, slow journey toward becoming a real player in security strategy. The bloc’s unique institutional flexibility has allowed it to wriggle out of many tight spots. One could always assume that it will manage to do so again, despite Brexit, the migration crisis, terrorist attacks, the cooling of transatlantic relations, and a host of new challenges and threats, including on the southern flank and in Russia’s new “hybrid Cold War” against the West. The worst-case scenario of a security collapse, in this context, must still be viewed as the least likely.