President Macri’s reelection will hinge on economic rebound

Argentina’s President Mauricio Macri is in a tight spot before the elections. His government presides over cuts to public spending to secure a lifeline deal with the IMF. Mr. Macri’s hopes for inducing growth by restoring Argentina to the good graces of the financial markets did not materialize. But not all is lost for the pro-market reformer.

In a nutshell

- Argentina’s reformer president Mauricio Macri chose a gradualist approach to sorting out the economic mess left by his Peronist predecessor

- His calculations that Argentina could return to growth quickly by regaining the financial markets’ trust and attracting investment failed to work

- Mr. Macri’s bid for reelection hangs under a cloud of IMF-mandated austerity, but the opposition is held hostage by his unelectable predecessor

When Mauricio Macri was elected Argentina’s president a little more than three years ago, his victory was met with enthusiasm both in and outside the country. It had become apparent that the previous Peronist government of Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner was driving the country toward economic and geopolitical disaster. Its public finances were in shambles, with fixed capital and foreign exchange controls. The international capital market was closed to Argentines and rumors of vast corruption filled the pages of the nation’s newspapers. The national statistical institute was forbidden from publishing official data: only Ms. Kirchner’s control over the nation’s money-printing presses kept the merry-go-round going.

Mr. Macri started with a weak hand: he eked out a narrow electoral victory and his political coalition, Cambiemos, did not have a majority in the Congress nor political control of most of the country’s provinces. Nonetheless, a predominant view was that the new president was reorienting the country in the right direction and that everything would work out eventually. Indeed, the leader accumulated much goodwill during the first months of his administration – around the world and, most importantly, among lenders in the international capital market. His somewhat shaky political position, however, has had consequences.

Failure of gradualism

Committed to protecting the most vulnerable in Argentine society, without whom he would not have won the election, Mr. Macri has chosen a gradualist approach to reform the country mismanaged by Ms. Kirchner. He rejected suggestions from the more orthodox economic advisors who favored a more drastic “shock therapy” on the assumption that it would bring the economic revival sooner.

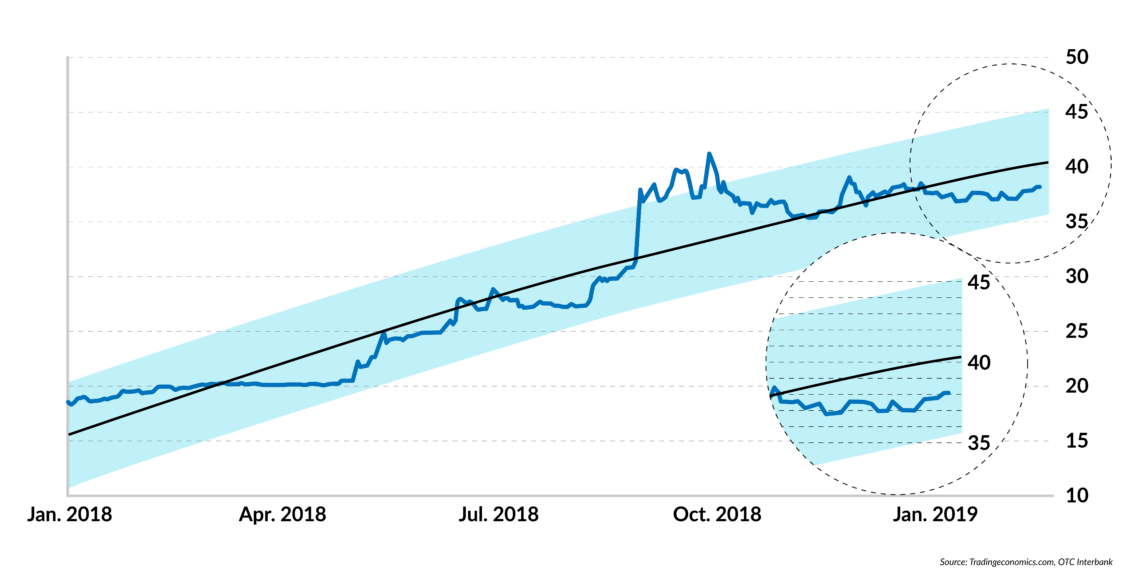

To keep the economy afloat, the Macri government used its newly burnished reputation in the international market to borrow the money it needed to balance the nation’s books. The underlying assumption of the gradualist strategy was that the restoration of confidence in Argentina would stimulate investment, both domestic and international, and reduce the need to borrow over time. This never happened. After four successive quarters during which external forces such as rising interest rates in the United States and the depressed market in agricultural commodities pushed up inflation and government debt in Argentina, investors lost confidence, and in the second quarter of 2018 began a run on the Argentine currency, the peso.

Facts & figures

Exchange rate, the U.S. dollar to Argentine peso (%)

At the end of May 2018, the game was up, and President Macri had to go to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) for help. By October, the IMF had promised to provide Argentina with a credit line of up to $57 billion, the largest bailout in the history of Latin America – on condition that the government would implement tight fiscal and monetary policies. The new policies did stem the run on the peso, but, from Mr. Macri’s point of view, the IMF-imposed conditions were the shock treatment that he had tried to avoid.

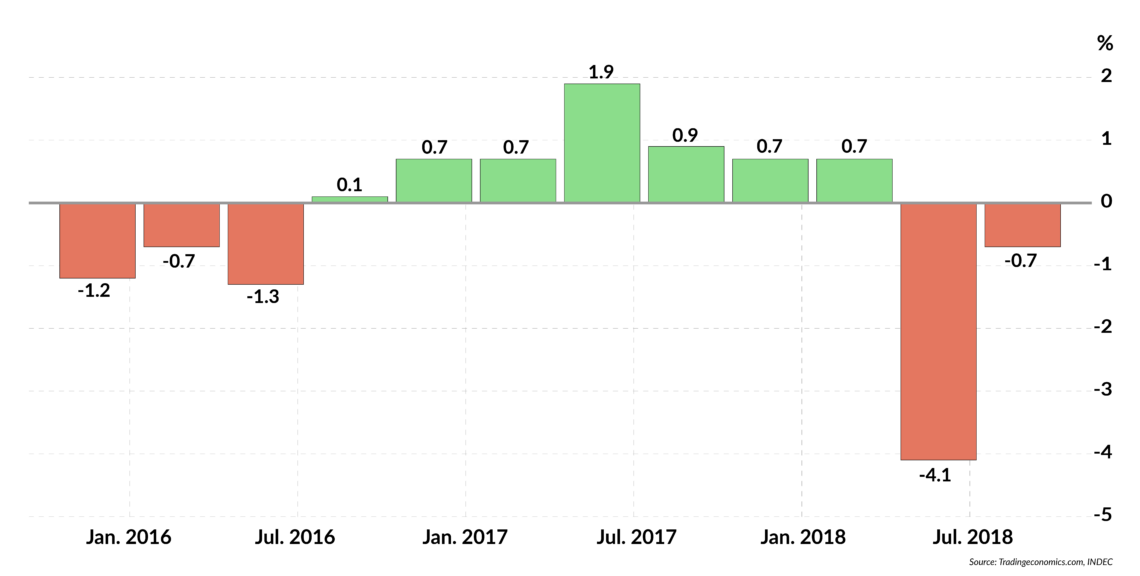

And now, in an election year, the government is forced to operate within tight spending limits. It cannot borrow to maintain programs that otherwise would break the budget. At the same time, an unfolding scandal surrounding the Kirchner administration’s abuse of construction projects has scared investors away from Argentina’s new public-private partnership (PPP) system. Mr. Macri had hoped it would help finance the badly needed infrastructure expansion, one of the pillars of the government’s growth strategy. The PPP program originally contained more than 40 projects worth over $21 billion. Now that only a few road projects will be financed “with bits and pieces,” as the country’s finance minister put it, the prospects for jump-starting economic growth look dimmer. Observers agree that the economy will contract in 2019. The only disagreement is by how much and how long the recession will last. The political and social consequences of austerity have created a nightmare for Mr. Macri’s government and thrown into question his reelection in October this year.

Facts & figures

Argentina's GDP growth

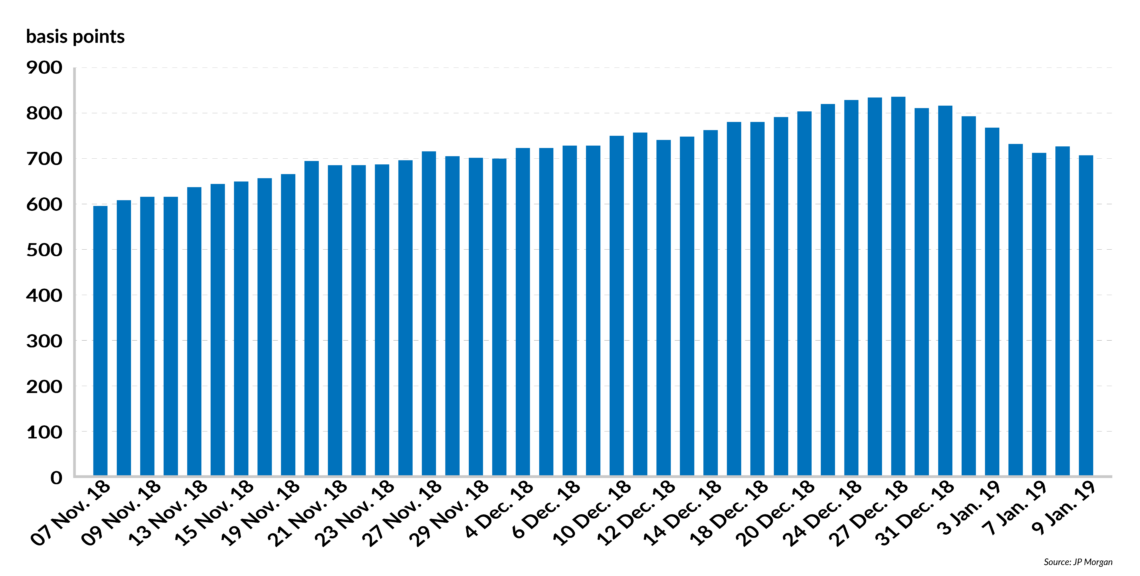

The daily focus of financial news in Argentina has been on what is known as Country Risk, a subindex prepared daily by JP Morgan. That index has fluctuated lately between 650 and 815 basis points (having been at 450 at the end of 2017), which suggests that Argentina is not a safe place to invest your money. In Latin America, only Venezuela features a higher spread number.

Facts & figures

Country Risk indicators for Argentina

Seeing the index’s volatility on the front page of every paper every day induces panic not only among bond investors. However, assuming the government’s ability to continue living within its means, the long-term health of the Argentine economy will be determined by the strength of the agriculture sector. In 2018, Argentina experienced its worst drought in half a century. In the coming harvest, however, analysts expect results at or close to historic highs. The swing would be a positive shift of more than $5 billion for the sector. That, in turn, would mean a significant increase in the government’s revenue from export taxes in 2019.

Facts & figures

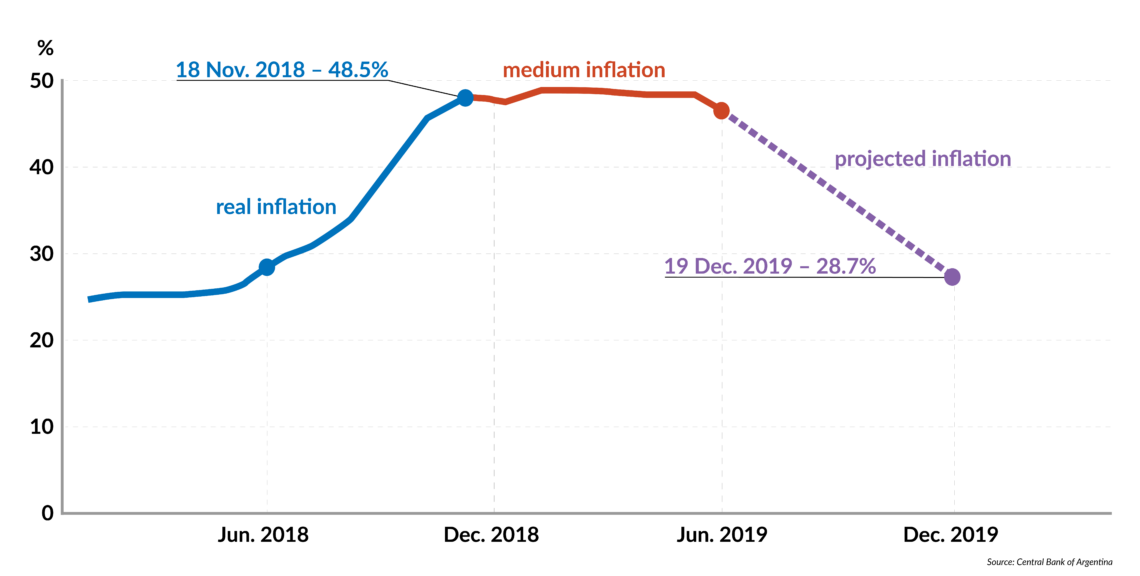

Inflation in Argentina

Annual Consumer Price Index, market expectations survey, Dec. 2018, variation in % annual

Political strategy

When Mr. Macri first entered office, he declared that he would bring Argentina back into the international community. As a statement of how he would reinvent Argentina’s role in world affairs, he lobbied in 2016 for his country to become the host for the November 2018 meeting of the G20. The successful organization of that important gathering was to be the coronation of Argentina’s reentry into global affairs, with attendant approval by public opinion. It did not fully work out that way.

The collapse of the peso stole the front pages of the local newspapers from the G20. Then, a head-to-head meeting of the presidents of the U.S. and China to resolve the brewing trade war between the two powers further diminished any attention that might have gone to Argentina in hosting the event. In fairness, the event was organized well and the government deserved more credit for it, although it did provide Mr. Macri with a positive bump in domestic public opinion.

Maintaining distance from the record of irresponsibility of the Kirchner administration should not be difficult.

Under the current circumstances, President Macri’s reelection strategy is straightforward. First, he will strive to keep his Cambiemos coalition together. The coalition consists of the president’s Republican Proposal (PRO), the Radical Party and the Civic Coalition. Mr. Macri may want to add some small parties on the left for the campaign, but for this to happen he would need to demonstrate his commitment to the social protection policies on which more and more Argentines depend, with the economy in recession. Such an undertaking would also be crucial to winning votes from the opposition Peronist party.

The second element of the president’s strategy is to hammer on the differences between his government and that of its predecessor. Maintaining distance from the record of corruption and irresponsibility of Ms. Kirchner’s administration should not be difficult. A lot will depend, however, on how the internecine conflicts among the various groups that form the Justicialist Party, or the Peronists, will unfold.

The Peronist factor

President Macri would prefer to run against Ms. Kirchner. He is less confident about running against one of the Peronist leaders who are not loyal to the former president. The country’s federal judges are pursuing a case in which Ms. Kirchner is alleged to have been the mastermind of a vast scam involving kickbacks attached to government contracts. As a sitting senator, she has immunity from prosecution, but the evidence keeps mounting and the headlines create a drumbeat of negative publicity. Despite this and the sense that she was the head of an incompetent cabinet that nearly brought the country to its knees, Ms. Kirchner’s support remains steady among some 25-30 percent of the Argentine electorate. This is about half of the Peronist vote concentrated in the populous counties surrounding the federal capital, Buenos Aires.

Within the Peronist party, several factions want to carry the party’s banner in the coming elections and believe that the former president is not electable. However, none of them dares to field a contender against her in a primary. All of the potential candidates, as well as the provincial governors who call themselves Peronists, are hoping that she will look for a way out of her impending conviction, take her money and leave the political field. At the moment, however. Ms. Kirchner shows no sign of retiring. The longer she holds on, the less power her Peronist competitors will accumulate, which favors Mr. Macri’s strategy.

There might be a way for Mr. Macri to undermine his chief rival’s candidacy for the presidency.

From this point on, things get complicated. President Macri does have one important lever in the electoral rules. The provincial governments have control over the dates set for primaries and general elections for local offices while primaries for federal offices (the so-called PASOs, Open, Simultaneous, and Obligatory Primaries) are fixed for August 11. In this election cycle, the governor of Buenos Aires Province, Maria Eugenia Vidal, can unbundle or detach the primaries for governor in her province from the presidential primary. Her province represents nearly 40 percent of the national electorate and in those densely populated counties around the capital, Ms. Kirchner has about two-thirds of her support. Ms. Vidal, however, is a loyal soldier in the Macri army. It is better for her boss to force the opponent to commit herself sooner rather than later to running for governor of Buenos Aires, which Ms. Kirchner has hinted is her Plan B. That might be a way for Mr. Macri to undermine his chief rival’s candidacy for the presidency. At this writing, 11 of the country’s 23 provinces have unbundled their elections but not Buenos Aires province nor the Federal Capital, both governed by Macri loyalists.

Changes in the pipeline

Also working in Mr. Macri’s favor is his administration’s advanced work on fundamental reforms which would benefit all Argentines over time. These efforts confirm the original notion that this president was taking the country in a new direction. In the Ministry of Security, for example, Secretary of State Alberto Fohrig has been hard at work spearheading the program professionalizing police forces on the federal and provincial level. That effort already has contributed to a decline in violent crime. Citizen insecurity, though, remains a major focus of public opinion. To show that he is tough on crime and make sure that his right flank is covered, President Macri has introduced a bill giving police officers more liberty to use guns in certain circumstances.

Another bright spot in Mr. Macri’s favor has been the fast pace of education reform in the province of Buenos Aires. Under Director General of Culture and Education Gabriel Sanchez Zinny, the province has embarked on an ambitious program of making education suitable for the new century. The program is focused on retention and standards in secondary education and seeks to bring teachers and students closer together in multidisciplinary projects so that both parties to the learning process feel engaged.

The program has had some notable successes: the retention and access numbers have improved. Remarkably, given the charged political context of labor relations, Mr. Sanchez Zinny has succeeded in creating standards for teachers in the system. The key to the compromise with the powerful teachers’ union was the explicit, transparent system of rewards for teachers who met the new standards. The more successful the Buenos Aires program, the more likely that it will convince the various provinces that run their education systems to copy the success. Successful education reform has immediate political implications, to say nothing of the mid- and long-term economic and social returns.

The question of governance

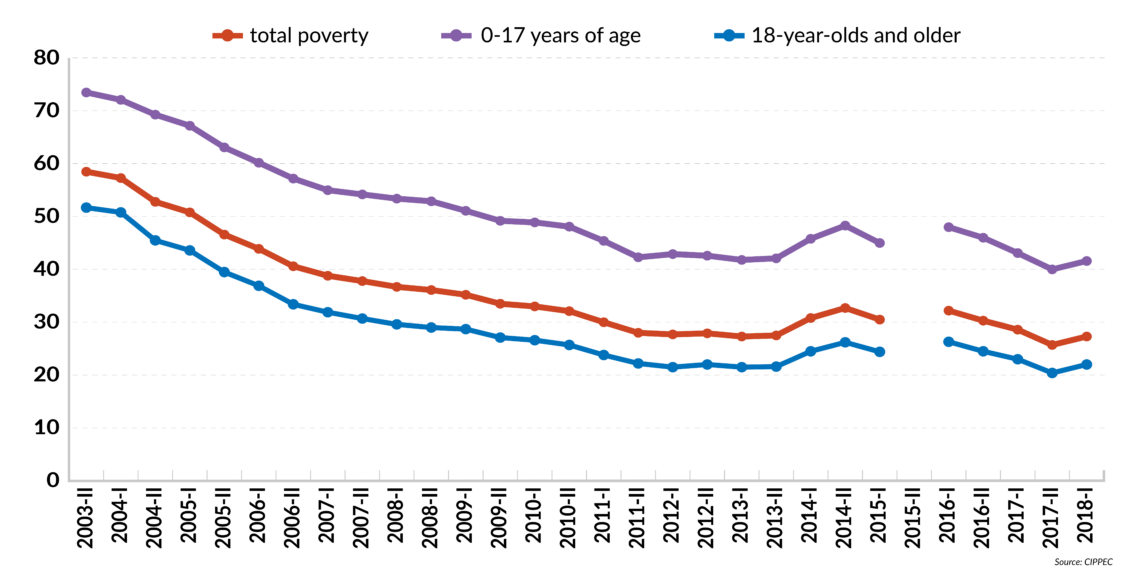

The question of social returns brings us to the issue of governance, which will be crucial for Mr. Macri in the coming election, as there are many more votes for him to seek among the Peronists on his left than on the right side of the spectrum. Despite the interest of his more progressive allies in the Cambiemos coalition, the government does not have a comprehensive strategy to tackle poverty. It does, however, have a package of long-standing social programs that could be used to mitigate the adverse effects of the current crisis. Given that poverty is concentrated in families with children, the government can reinforce the Universal Child Allowance (AUH by its initials in Spanish), the Pregnancy Allowance and other programs designed to protect the most vulnerable sectors of society, such as youths and the elderly.

Facts & figures

Poverty rates in Argentina

In the short term, the most politically charged element of the economic situation is that in rising inflation, local costs tend to increase much faster than income for the working poor. That is particularly painful for nearly one-third of the working population that is engaged in the “informal” economy. For example, the IMF deal requires the government to bring the costs of public services under control, although it does explicitly accept that the government may spend up to 0.2 percent of GDP on social spending. That means that the subsidies provided by the government must be reduced.

The most likely scenario is that President Macri will be reelected, defeating Kirchner or some other Peronist leader.

The fate of social programs under Mr. Macri is still unclear. The budget for the new year, passed in Congress by a multiparty vote, includes a full arsenal of programs that the federal government might use to ameliorate the pain of austerity. However, the federal government already began at the end of 2018 to shuck off a portion of its responsibility for cofinancing assistance programs for the most vulnerable groups, such subsidies for their electricity consumption, to the provinces and the city of Buenos Aires. That shift was written into the 2019 budget and it is unclear how the several provinces will confront their new responsibilities to their vulnerable populations.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that President Macri will be reelected, defeating Cristina de Kirchner or some other Peronist leader by highlighting the difference between his responsible path and the disaster of what came before. In this scenario, the economy begins to show signs of stability by the second quarter of 2019. The improving harvest, together with increasing income from tourism and beef exports, will help bring down inflation and the country’s risk numbers. As this happens, wages and government subsidies gradually catch up to rising prices and defuse the anger among voters.

A less likely scenario hangs on two developments unhelpful to Mr. Macri. The first is that Ms. Kirchner pulls out of the race for the presidency and gets her base to support the Peronist candidate. The second is that the harvest does not save the government and the rate of inflation does not start coming down in the fall. That would contribute to a sense of doom among the public, causing a new run on the peso. At the same time, voters would turn to the Peronist candidate to save them from the “Macri disaster” – whether that be Ms. Kirchner or an alternative such as Roberto Lavagna, a former minister of the economy under Peronist governments.