The U.S.-China AI race: A ‘third way’ for Europe?

As artificial intelligence becomes a key source of competition between China and the U.S., the EU is left behind. Europe has focused on regulations and the ethics of AI at the expense of technological development. It is now launching research initiatives, but time will tell if it avoids losing economic and geopolitical influence on the AI front.

In a nutshell

- Europe has been standing on the sidelines as China and the U.S. achieve global dominance in artificial intelligence

- After focusing too much on regulations and ethics, the EU is launching new research initiatives and spending more on AI

- China has amassed a trove of personal data on its citizens, which is valuable currency in the AI age

- The U.S. and EU must cooperate if they are to blunt China’s AI ambitions

The present trade war between the United States and China is only one part of an escalating race between the two countries for technological supremacy in the 21st century. Western experts have warned that China will have caught up to the U.S. in artificial intelligence (AI) technology by 2025 and that it will dominate the worldwide AI industries by 2030 — a potential AI “Sputnik moment” for the U.S. The AI revolution may even come faster than previous technology revolutions, as it will likely be driven by quickly replicating software rather than the hardware of the past, such as the steam engine.

In Europe, too, there are concerns that the continent is falling even further behind — risking not just jobs but its future economic strength and competitiveness, and, ultimately, its geopolitical influence. Over the last year, the EU’s China policies have significantly shifted, highlighted by the EU’s new 10-Point Strategic Outlook paper on China of March 2019. Europe has signaled a more assertive strategy toward China in which future bilateral cooperation will be guided by the principle of reciprocity (e.g., European firms having equal access to the Chinese market).

Strategic access to, and control of, unprecedented volumes of data —the feedstock of artificial intelligence — has become the new oil and currency of geopolitics in the 21st century. Against this background, the European Commission and major member states such as Germany and France have only recently started initiatives to support research and development of new disruptive digital technologies, including artificial intelligence. French President Emmanuel Macron demanded a European “third way,” recalling the Cold War path between capitalism and socialism, with new “creativity in the technology field.” Germany announced that it would spend 3 billion euros on AI projects over the next six years after a poll last year revealed that only 11 percent of all German companies are using or considering the use of AI.

Control of unprecedented volumes of data has become a new currency of geopolitics in the 21st century.

While the EU has been standing on the sidelines like an observer, U.S. tech giants (such as Alphabet/Google, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple and Facebook) and their Chinese counterparts (the IT champions Baidu, Alibaba and Tencent, and ICT giants like ZTE and Huawei) have been acting as the “gatekeepers to the internet” by amassing huge amounts of data from billions of users. China has also become the world’s second-largest investor in research and development, with $279 billion outlays in 2017, and is expected to surpass the U.S. within the next decade. It now hosts 227 supercomputers, or around 45 percent of those installed worldwide, compared with just 92 supercomputers in the EU. The EU has no comparable giant digital companies in the global top 15 by market capitalization and accounts for only 4 percent of the leading 200 online platforms.

More than regulations?

The European energy, education, healthcare and transport sectors have been regulated considerably for decades. These experiences can inform the approach to regulating AI and digital technologies in the name of creating a balanced, democratic internet, with strong privacy-protection rules toward the U.S. and other tech giants. The EU has already strengthened its data privacy rules in the new, controversial General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR). Even American tech giants have at least partly accepted the GDPR as the “best bad idea in town” to regain and preserve the trust of its users.

In early April, the European Commission adopted its first guidelines for the ethical development of AI. As in other industries, the use of AI technologies and programs must comply with existing regulations on data privacy, consumer protection and environmental standards. It has warned that algorithms cannot discriminate based on age or race, and defined seven principles for ‘trustworthy’ projects.

Facts & figures

European Commission AI guidelines

- Human agency and oversight

- Technical robustness and safety

- Privacy and data governance

- Transparency

- Diversity, nondiscrimination and fairness

- Environmental and societal well-being

- Accountability

Officially, the European Commission sees these AI guidelines as an added value, and not as a threat to future innovation (as experts have warned). These guidelines have already attracted interest in Japan, Australia, Canada, Singapore and other countries who are seeking answers for balancing regulations and opportunities. But despite the growing interest abroad and increasing financial support of the EU and its member states toward digital and AI technology, it may be too little, too late to catch up with the U.S. and China.

Whether the EU, which appears to rely primarily on soft skills rather than hardware, will remain influential in the mid- and long-term without any companies among the global AI leaders remains somewhat doubtful. A politically divided and fragmented Europe may have a hard time competing with an ambitious and nationalist China that pursues its narrowly-defined strategic interests at the expense of many other regional countries.

Furthermore, across sectors and industries, digital and AI technologies are always of a dual nature, allowing for civilian uses as well as military. Both governments and companies have to recognize that the economic and security dimensions of these dual-use AI technologies cannot be ignored, making their exports to and possible applications in other countries problematic. These technologies will increasingly impact regional and global military balances of power.

Future AI superpower

China’s digital rise and its massive tech investments, as well as unique party-state-private nexus and its country-wide use of AI-enabled facial- and voice-recognition technologies, have enormous implications for its governance model as well as for foreign markets. The development of digital technologies in China has strengthened its control over its companies and critical infrastructures. It has already become a worldwide technology leader. But it has also allowed unprecedented, 24-hour control over its citizens to enforce compliance with its autocratic political system. No other state in the world has come as close to the Orwellian dystopia as China.

Facts & figures

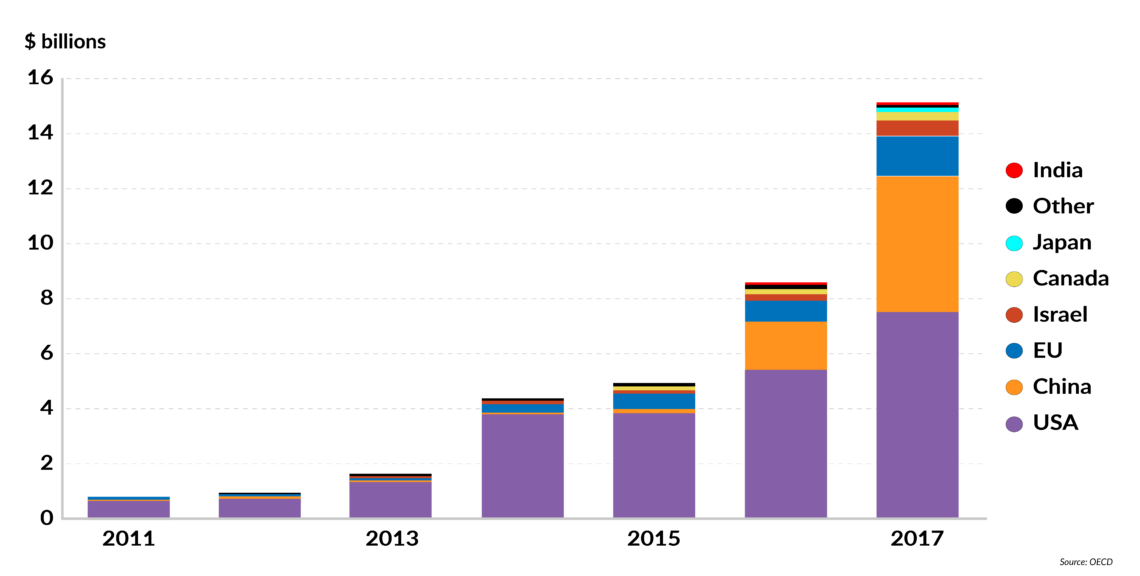

Total estimated private investment in AI start-ups, 2011-2017

Abroad, Chinese high-tech and digital state-owned enterprises have expanded their market share as well as geo-economic influence. This allows Beijing to intervene in smaller countries’ economic and foreign policy decisions, and to try to divide and rule the EU and ASEAN. Its “digital silk road” is part of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), while its Made in China strategy seeks global technology leadership of AI across all industries by 2025.

China’s 2017 Cyber Security Law guarantees that foreign access to its ICT sector remains restricted, due to regulations on data and cybersecurity as well as numerous informal barriers. Its new “Social Credit System” also enforces conformist behavior and compliance by companies and citizens.

By proclaiming a digital silk road, China has begun to invest worldwide in digital critical infrastructures such as overseas fiber-optic cables, telecommunication and internet infrastructures, data and cloud computing services, global positioning, wireless communications and smart city sensors. This headway has attracted attention but has also increased global concerns about China’s ultimate strategic objectives. The potential insertion of backdoor viruses and mechanisms could increase China’s industrial and political espionage, intelligence and propaganda missions in the BRI partner countries.

Beijing is suspected of being willing to export its notorious internet censorship tools and its comprehensive political control of data collection and traffic with the BRI, just as it seeks to ship its autocratic political system to neighboring countries to bolster its regime stability. All of this raises issues of human rights, personal freedom, privacy, and anonymity.

China’s digital rise and its massive tech investments have enormous implications for its governance model and foreign markets.

The context is a global ascendancy of autocratic states (such as China and Russia) with an imposing economic influence, rising digital and AI competency, and the political will to use their financial soft power to divide and weaken Western democracies. Those concerns have increased in the West as the global share of “not free” and “partially free” countries has grown from 12 percent to 33 percent in 2017 — a level not seen since the early 1930s. Both China and Russia are using digital technologies as part of their hybrid warfare and economic strategies to weaken the security of Western powers as well as their political-social cohesion.

China’s digital policies have also produced increasing challenges for the economic investment strategies of the BRI, heightening various contradictions of its economic and foreign policies and raising questions of China’s goals and ambitions. China is still dependent on U.S. chipmakers (such as Qualcomm or Nvidia) and semiconductor companies, though it is building up its own for national security reasons. Like other countries, China is also facing major challenges in delivering the AI advances that investors are hoping for.

The bilateral AI race does not have to be a zero-sum game for both sides and more cooperation might produce benefits not just for the two technological superpowers but for the entire global economy. Chinese President Xi Jinping’s nationalist policies and domestic agenda, however, carry clear implications for China’s foreign and security policies. It has become assertive by defining international standards in the International Standard Organization (ISO) and its global telecommunication and ICT-sectors such as in the ISO’s 5G group.

In contrast to Europe, China benefits not just from a more AI-friendly policy and societal environment and its deep learning curves, but also its unprecedented amount of data available. This trove is credited not only to China having the world’s largest population, but to its collection of as much data as possible on its citizens — a necessary condition for its model of internet governance, based on total control and mistrust of its population. Becoming the “Saudi Arabia of data” would be impossible in a democratic country.

Facts & figures

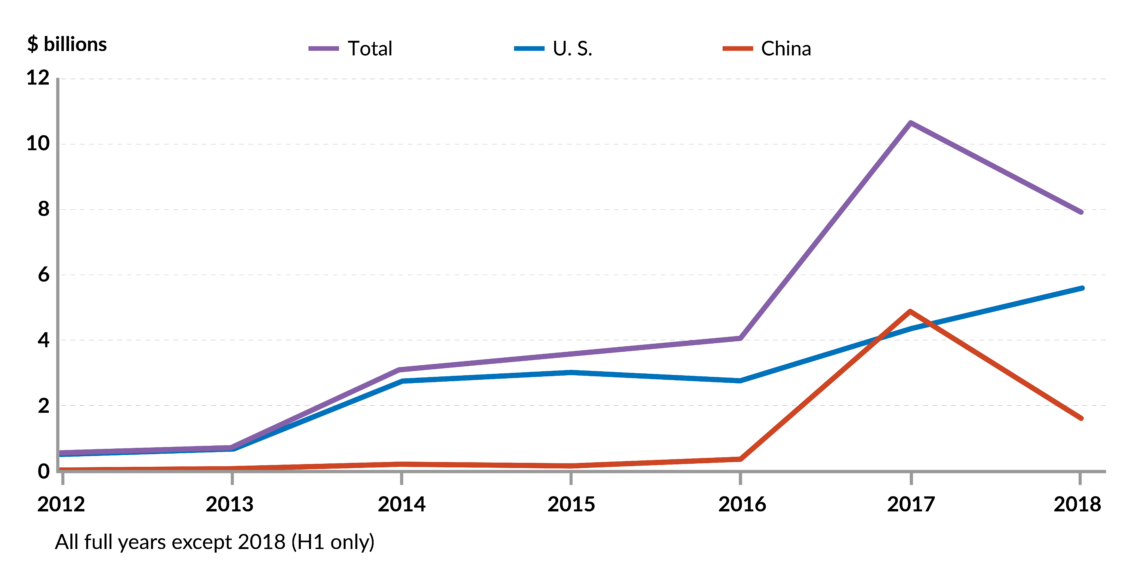

Private investment in AI, U.S. and China

With China offering access to this kind of data, it is hardly surprising that European and U.S. digital and AI companies (for example, Siemens AG) are relocating their AI-research and development centers to China, despite Western government concerns. The effect is to thwart Europe’s aspirations to catch up with China on AI and enhance the Asian giant’s geo-economic influence. Ultimately, the process might further increase Europe’s illicit technology transfers to China and its future dependence on Chinese AI technologies and companies.

Transatlantic cooperation

To be sure, the U.S. and EU are technology rivals and there are growing European concerns about the activities of American intelligence services and digital ethics and data privacy. However, those differences can be overcome as both sides – despite President Donald Trump’s occasional leanings — remain committed to and guided by democratic values, the rule of law and the individual freedom Western societies enjoy.

The transatlantic debates reflect different priorities (such as economic growth versus security interests) rather than clashing approaches and are not the result of fundamentally conflicting world views. Both sides are still struggling to find the right answers to digital and AI challenges (such as regulations and openness for digital innovation) by balancing opposing strategic objectives and interests. Thus, both sides were able to put the EU-U.S. Privacy Shield Agreement into force in August 2016.

Bolstered by shared geopolitical interests, the Western powers’ mutual strategic interests are likely to outlive President Trump’s legacy and cannot be effectively challenged by autocratic political systems such as China’s or Russia’s. Google, for example, has just established its own ethics committee, in which the EU ethical guidelines will be an important starting point and source of reference for its in-house discussions. It also matters that despite the bitter quarrels of the Trump era, U.S. and European markets and data spheres remain interwoven.

Furthermore, as it has recently revealed that, despite the bilateral trade conflict and the global power struggle, U.S. IT companies such as Microsoft have still cooperated with Chinese military-related research centers and universities on cutting-edge AI technologies for surveillance and censorship. This has caused consternation and anger in the U.S. Congress, across party lines. Research universities such as the Massachusetts Institute of Technology have already given up their research collaboration with Chinese companies like Huawei. The tension here highlights the transatlantic difficulties in attuning American and European commercial interests with major security concerns and risks, and the need for both sides to find a balanced answer — not just for themselves, but as a common transatlantic response.