‘Basel IV’ and the stability of the financial industry

Basel IV is a set of new standards that most international banks are expected to follow. Many in the industry criticize the rules’ complexity and restrictiveness, but regulators say they don’t go far enough. Everyone agrees, however, that more regulations are soon to come.

In a nutshell

- The latest batch of rules in the Basel process will introduce crucial changes

- Many in the banking industry say the rules are too restrictive

- Quantitative analysis shows they actually don’t go far enough

- More changes are in store, leaving the industry in uncertainty

The global financial crisis of 2007-2008 showed how undue risk-taking, and even fraudulent practices, had become commonplace in the banking industry worldwide. Supervisors and regulators watched helplessly as a sudden cascade of major bank failures plunged the leading economies into a severe (and to some extent still ongoing) recession. For the next decade, overcoming the weaknesses of existing national and international regulatory frameworks became a top priority.

When the crisis hit, several regulatory safeguards were already in place that were supposed to prevent a banking system collapse. Among them was the set of recommendations on banking regulations put forth by the Basel Committee on Bank Supervision (BCBS).

The very first Basel Accord (also known as Basel I), was finalized in 1988 and came into force in 1992. It prompted banks with an international presence to hold capital reserves large enough to cover the risks incurred by their credit operations.

From Basel I to Basel II

Above all, Basel I provided an “asset classification system” for determining banks’ credit-risk profiles. Five risk categories were proposed, based on the identity of the debtor: 0 percent, 10 percent, 20 percent, 50 percent and 100 percent. Debts incurred by central banks and government within the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) are classified as zero-risk. Other public sector debt can be found in categories one to four, depending on the borrower. Residential mortgage-backed assets are typically associated with a risk of 50 percent. All remaining private sector debt is classified as 100 percent risk.

Critics argue that Basel I sowed the seeds of the housing bubbles that led to the American subprime crisis.

The rule is simple: international banks’ capital buffers should equal 8 percent of their risk-weighted assets (RWAs).

In 2004, while retaining this basic rule concerning minimum capital requirements (CRs), the Basel Committee came up with a second, more ambitious, framework: Basel II. Among other things, it offered more elaborate models for measuring banks’ capital. Under Basel I, the term “capital” was defined broadly, encompassing vague items such as “intangible goodwill” as a bulwark against risk.

Similarly, risks had only been crudely differentiated, without accurately considering the creditworthiness of individual borrowers. Critics argue that the regulator-set risk classification of assets introduced by Basel I adversely shaped banks’ lending decisions, thus sowing the seeds of the housing bubbles that led to the American subprime crisis in 2007 and, a few years later, the European sovereign debt crisis.

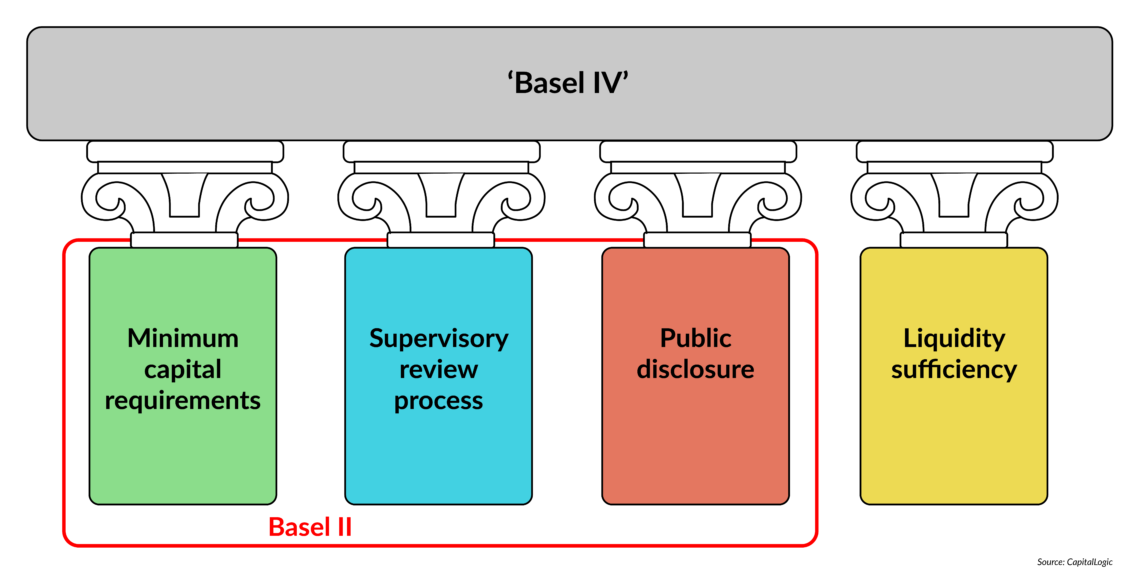

To overcome some of its predecessor’s shortcomings, Basel II builds on three pillars:

- Capital adequacy requirements: aimed at covering credit risk, market (or systemic) risk and operational risk

- Supervisory review: aimed at fostering exchanges between banks and supervisors

- Market discipline: aimed at compelling banks to comprehensively report on their internal management systems

The problem with the new regulatory setting is its sheer complexity. Amended several times since 2004 (among others, in 2009, by “Basel 2.5”), Basel II has never been fully and consistently implemented in the United States or the European Union, due to disagreements among negotiators.

Basel III promises

A long-awaited Basel III Accord was announced in 2010. From the start, it was marketed as an unforgiving process of “reregulation,” in which the lessons learned from the crisis were considered. Above all, as pointed out by the BCBS Chairman Stefan Ingves, the new package of reforms was supposed to repair the public’s lost confidence in the financial system. When it comes to capital requirements, Basel III sets the minimum of total capital (including conservation) buffers at around 10.5 percent for “global systemically important banks” (so-called G-SIBs).

Basel III established a global minimum standard for liquidity.

Moreover, it put forth a tighter definition of the term “capital” (now defined as “tangible common equity”). The aim was to increase both the level and quality of capital requirements.

Basel III also established a global minimum standard for bank liquidity, called the “liquidity coverage ratio” (LCR). This refers to the amount of “high-quality liquid assets” (HQLAs) financial institutions should hold to stay operational for at least one month in case of a bank run. In addition, the “net stable funding ratio” (NSFR) should incentivize banks to finance their activities with more stable sources of funding over a longer (one-year) time horizon.

Finally, and most importantly, Basel III challenged banks’ methods for calculating their risk weights. This is clearly the centerpiece of Basel III, whose proclaimed aim is to “restore credibility in the calculation of RWAs and improve the comparability of banks’ capital ratios.”

Calculating risk weight

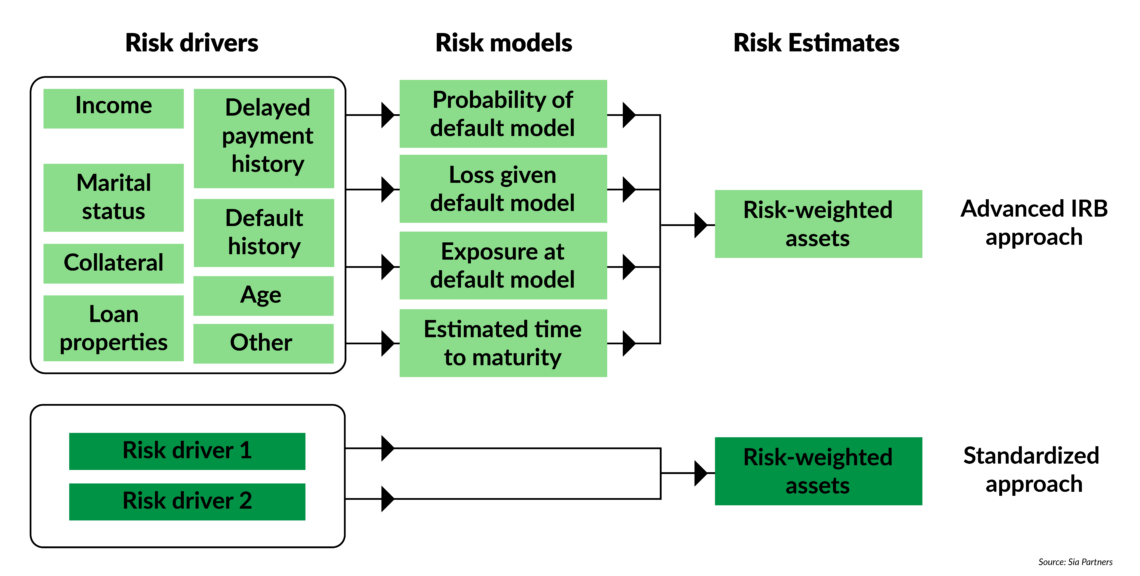

Under Basel II, banks were given the choice between two broad methodologies for estimating their RWAs and, ultimately, determining their capital requirements.

The first was a “standardized approach” based on the average risk weight associated with given loan categories, as defined by external credit rating agencies.

Facts & figures

RWA methodologies

A second option was offered to systemically important financial institutions. Subject to supervisory approval, they were allowed to rely on so-called “internal ratings-based” (IRB) and, crucially, “advanced internal ratings-based” (A-IRB) methods, to quantify the equity capital required to cover risks.

Under A-IRB, each bank could – by itself – assess fundamental risk parameters such as probability of default, exposure at default and loss in case of default, before building up capital buffers accordingly. In other words, Basel II allowed large banks to be the sole judges of their riskiness. Consequently, banks’ reported capital-to-RWA ratios based on A-IRB could vary greatly from one institution to another – up to 50 percent for the same hypothetical portfolio, according to studies conducted by the Basel Committee.

The 2008 crisis made clear that many banks inaccurately evaluated certain classes of assets (in particular, residential mortgage-backed securities) held in their balance sheets. Opacity and discretion seemed to rule internal risk-modeling in the industry. Hence, some major financial institutions ended up dangerously overleveraged, with the consequences we now know – the collapse of Lehman Brothers being just the most famous example.

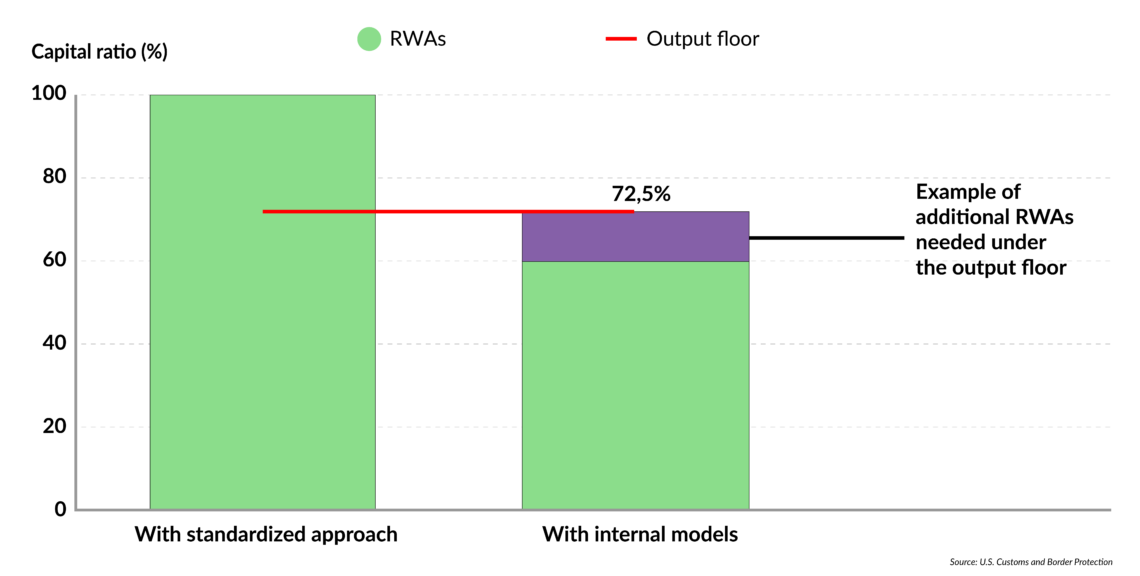

In 2016 and 2017, changes were agreed upon to “complete” Basel III. The changes would not ban banks’ internal risk calculation methods altogether. Rather, they stipulate that capital ratios calculated with internal models should not fall below 72.5 percent of the result that would be obtained if a standard, market-wide (one-size-fits-all), method of risk-weighting was applied. This lower limit is labeled the “output floor.”

Nickname: Basel IV

Most banking professionals, tired of increasingly restrictive reforms that threaten their profitability, do not welcome these proposals.

It is true that the European financial industry has had to cope with many new regulations, some of them transpositions of Basel guidelines into EU law. These include the Capital Requirements Directives (CRDs), the European Bank Recovery and Resolution Directive (BRRD), the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive (MiFID packages I and II) and the Solvency II Directive, which have considerably thickened the alphabet soup of postcrisis financial regulation. On the international level, an additional layer of protection has been imposed on G-SIBs in the form of “total loss-absorbing capacity” (TLAC). At the EU level, a “minimum requirement for own funds and eligible liabilities” (MREL) is applicable to all banks.

Many bankers see the new risk-weight calculation rules as the straw that could break the camel’s back.

Apart from higher equity and other buffers to absorb losses, banks are subject to ever-tighter reporting requirements and undergo regular stress tests, in which supervisory agencies assess whether they can withstand adverse shocks to the economy.

Many bankers see the new risk-weight calculation rules as the straw that could break the camel’s back. Given the scale of change the new regulations threaten to introduce, they collectively have nicknamed them (maybe not without a certain sarcasm) “Basel IV.”

Bankers’ scenario

Bankers think that if “Basel IV” were implemented, they might need to increase their capital cushions significantly. A recent study shows that, for corporate and housing loan exposures for instance, European banks would need to hold more than twice as much credit-risk capital under the standardized approach than they would under A-IRB.

Facts & figures

Basel III's 'output floor'

For housing loans, the standard (external or market-based) risk weight would be 35 percent, while banks could evaluate the same risk as low as 10 or 15 percent by using internal methods, based on the profile of their actual customers.

The new Basel regulation, bankers say, will jeopardize the commonsense link between risk and capital, as it forces them to increase equity capital in a way that does not reflect increases in risk. Institutions holding low-risk portfolios (such as mortgages and loans to creditworthy households and stable businesses) will now be required to hold capital as if they had high-risk portfolios. The cost of capital associated with low-risk loans would therefore increase. This, in turn, would lead to an unnecessary withdrawal of capital from the economy that might otherwise be safely lent to investors apt to create jobs and generate growth.

This reduced cost-effectiveness, the argument goes, is all the more damaging because the new Basel rules are being applied to European banks just as they are losing significant market share to American and Asian rivals.

Above all, it is often argued, lenders’ incentive structures might be altered by “unreasonably” high capital requirements. Banks could be inclined to prefer high-risk loans (which yield higher returns) to less profitable ones granted to ordinary families seeking to finance their homes or entrepreneurs developing their local businesses. Hence, the latest Basel amendments, designed to strengthen the financial system, could end up undermining its stability by fueling a debt trap, bank lobbyists warn. Are the bankers right to say that the new Basel III recommendations go too far?

Economists’ scenario

William R. Cline, a renowned expert on financial markets and researcher at the Washington-based Peterson Institute, insists that “excessively” high requirements for equity capital in banks is indeed a bad idea. Lending rates might actually rise, as some of the costs induced by higher credit requirements would be passed along to the wider economy, hindering productivity in the long run.

Regulators’ challenge is to strike a balance between financial safety and potential costs to economic activity.

Still, Mr. Cline asserts that significant credit requirements are indispensable in making bank failure and systemic crises less likely. The challenge for regulators is to strike the right balance between financial safety and potential costs to economic activity.

All this leaves us to ask what equity capital level is optimal for banks to stay safe, and where does Basel III stand with respect to this optimum?

Quantitative economic analysis shows that Basel III does not go far enough. Mr. Cline’s empirical findings imply that banks’ equity capital should be 12 to 14 percent of their RWAs, corresponding to 7 to 8 percent of their total assets.

This is significantly higher than the Basel III recommendations, which, as mentioned before, only require the largest banks to cover their risks with a capital cushion of 10.5 percent of their RWAs, on average corresponding to 5 percent of their total assets.

Regulatory doom-loop

Over the past decade, the ratio of RWAs to total assets (called “RWA density”) has been drifting downward in many countries. In 2017, it was estimated at 44.84 percent worldwide. In Western Europe, it plunged to 31.9 percent within a few years, which is considerably lower than in the U.S. (56.8 percent), where banks seem to be building up risk again.

This trend may be due to European banks’ overall willingness to “de-risk” their balance sheets by deleveraging – meaning that banks are becoming safer. However, it can also be explained by the fact that, under the Basel III framework, OECD sovereign debt continues to be considered risk-free (which may seem odd, considering the European sovereign debt crisis that endangered the euro area and its currency in 2009-2011).

The Basel framework itself encourages banks to load up on such zero-risk-classified debt.

It is obvious that European banks’ persisting taste for sovereign debt securities is not only due to the naturally strong link between domestic banks and governments (what some call a “home bias”). Rather, it is the Basel framework itself that encourages banks to load up on such zero-risk-classified debt, for which there is no capital counterpart required. In the coming years, this paradox inherent to Basel III could again fan the flames of sovereign risk in Europe. Recently, the Basel Committee commissioned a discussion paper on the matter, but no consensus could be reached so far.

Endgame

The Basel III “endgame” (as European Central Bank President Mario Draghi named the final accord) was settled on December 7, 2017, after endorsement by the Group of Governors and Heads of Supervision (GHOS).

For seven years, negotiations had largely been running on empty. The technical complexity of the project’s most thorny reform matters (the calculation of regulatory capital requirements alone includes several thousand parameters) and the diverse views of the stakeholders involved were invoked as the main reasons behind the delay.

In the end, Basel III turns out to be a compromise agreement. Through the years, the BCBS had backtracked on or watered down some of its key recommendations. Also, the schedules for putting the reforms into practice were considerably stretched. A 10-year timeline is proposed, starting with a five-year “phase-in” period (beginning January 1, 2022), followed by a progressive implementation period of five more years. For example, the 72.5 percent output floor should be effective only by 2027 – exactly two decades after the financial crisis precipitated Basel III.

As economic journalist Rita Lobo put it, the problem is that each time rules are bent and deadlines deferred, the final regulation gets weaker. “Basel III is only, and will only ever be, a stepping-stone on the way to Basel IV and whatever else lies beyond,” she concluded.

Banks are assured of nearly a decade of regulatory status quo before they feel the full effects.

Without a doubt, this is good news for the big bank lobbies, whose alarming scenarios on what they call “Basel IV” should now be put in perspective. Banks are assured of nearly a decade of regulatory status quo before their current risk-management practices feel the full effects. And they are quite aware that a lot can happen before then.

Basel III’s efficiency will also depend on how the reforms are implemented. As Chairman Ingves emphasizes, the BCBS has no supranational authority, its decisions carry no legal force, and it cannot impose fines or sanctions for noncompliance. All it does is define “global minimum standards” and hope for countries to integrate them into national law. In the end, much will depend on the interpretations national (and EU) lawmakers give. Banks’ strategic responses are no less important.

Basel Committee Secretary General William Coen himself admits that the recently finalized accord “may not necessarily reflect a theoretically ‘first best’ outcome.” What worries him is the emergence of new risks within the banking industry caused by the fast pace of financial innovation, to which the current regulatory framework has not yet adapted.

“There will be a Basel IV at some point in the future, even if it may not be called as such,” Mr. Coen has said. Still, he does not anticipate this will happen “anytime soon,” maybe because the new agenda would entail still greater regulatory complexity, something even the most die-hard regulators no longer consider desirable.

The only thing Mr. Coen allows himself to affirm “with a fair degree of certainty” is that “the Basel framework in place today will not be the same one in place” 10 years from now. In short, the only certainty at this stage appears to be that no regulatory certainty whatsoever can be expected for the global banking sector. We are left with the burning question: How safe will the financial system be in the years to come?