Pyongyang may determine the U.S.’s North Korea policy

The threat posed by North Korea remains a forefront foreign policy concern for the United States. So far, the new leadership has stuck to strategies already in place – but North Korea could gain an advantage in negotiations with President Biden.

In a nutshell

- The U.S.’s Northeast Asia policy is mostly unchanged

- Pyongyang will want to test the new administration

- In a crisis, North Korea could pressure the U.S.

The United States’ Northeast Asia policy did not radically change from the administration of Donald Trump to the presidency of Joe Biden. Though Chinese influence is increasingly causing worry, North Korea’s nuclear proliferation remains at the center of U.S. concerns. Washington’s stated interest is still to work toward full denuclearization and strengthen bilateral relations with both South Korea and Japan. But the Biden team may find itself challenged by the North Korean regime. As a result, Pyongyang, not Washington, could set the future agenda and shape both diplomatic efforts and security policy.

From pressure to patience

The Trump administration policy toward North Korea consisted of two tracks. On one hand, the U.S. moved to safeguard Americans and regional allies against the North Korean nuclear threat by an offense/defense mix of conventional and strategic deterrence and missile systems. On the other, Mr. Trump offered a diplomatic off-ramp to the North Korean regime, but only after it assented to full and verifiable denuclearization. While Pyongyang tested Washington’s resolve, the Trump team remained undeterred.

At the same time, the U.S. maintained strong bilateral ties with both South Korea and Japan, despite persistent tensions between the two states. There was also friction between the Trump administration and both countries over trade, and Washington and Seoul disputed cost-sharing responsibilities for U.S. troops in South Korea.

The US Northeast Asia policy did not radically change from the administration of Donald Trump.

One area of relative continuity between the old and the new administration has been the Indo-Pacific. The Biden team has adopted similar policies toward the Pacific Islands, the South China Sea, Taiwan, Hong Kong, the Uighur genocide, Tibet and the Quad (a diplomatic framework comprising the U.S., Australia, India and Japan). Much of the credit for this stability is attributed to senior White House policy advisor Kurt Campbell.

There were no major changes in Northeast Asia policy either. The U.S. and Japan have both reaffirmed strong bilateral ties. Relations with South Korea are also strong, though not without challenges similar to those faced by the last administration. The U.S., for example, continues to hope for better South Korean-Japanese bilateral relations, but for domestic reasons, both countries are reluctant to undertake new initiatives. Washington would like Seoul to take a tougher stance on Beijing. The South Koreans, however, are reluctant to antagonize China because of the deepening economic ties between the two countries. Meanwhile, the U.S. and South Korea have largely resolved disputes over burden-sharing for American forces stationed on the peninsula.

The most significant dispute between the two governments is over policies toward the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea (DPRK). The administration in Seoul would prefer sanctions relief to induce more cooperation from Pyongyang. The U.S. has demurred.

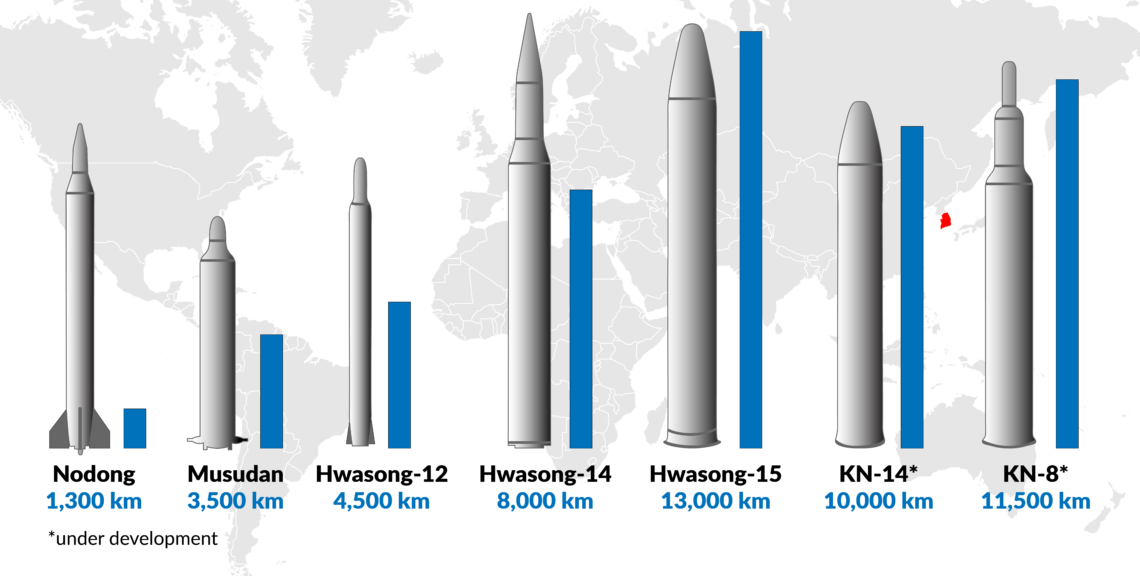

Facts & figures

During South Korean President Moon Jae-in’s recent visit to Washington, the differences between the two governments were largely papered over. Both sides emphasized the positive aspects of the relationships, signaling content with the status quo.

Pyongyang often studies U.S. negotiations with Iran for cues on how to approach American negotiators.

Washington has publicly committed to maintaining sanctions and insisting on North Korea’s complete denuclearization. One U.S. official quoted in a recent media interview stated, “We fully intend to maintain sanctions pressure while this plays out.” The Biden administration, however, does seem to be more open to a step-by-step approach, offering targeted relief for concrete measures.

The White House wants to demonstrate strategic patience and wait for positive overtures from Pyongyang, stating it would not seek another summit until there was substantive diplomatic progress. The Biden team has also said it will be more vocal about North Korean human rights violations. As an American expert on the region, Bruce Klingner, sums up, “the Biden administration’s proposed ‘calibrated’ and ‘careful, modulated diplomatic approach’ appears consistent with U.S. policies since the 1994 Agreed Framework.”

North Korea’s move?

The North Korean government has adopted a mostly belligerent attitude toward the new administration, though it has not undertaken any significant acts such as long-range missile, nuclear tests or military actions (like artillery shelling of South Korean territory or provocative acts at sea).

Pyongyang often studies U.S. negotiations with Iran for cues on how to approach American negotiators. The Biden team seems anxious to reach a deal with Iran and could offer broad concessions to Tehran including significant sanctions relief. North Korea may well demand similar treatment. Washington’s wait-and-see attitude could allow Pyongyang to set the tone in future relations.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario is that North Korea will test the resolve of the new administration. The DPRK will not appreciate the Biden team’s tough talk on denuclearization, sanctions and human rights. It could respond by conducting a major provocation like direct military action, a nuclear test or long-range missile firing. The regime will want to challenge Washington’s commitment to denuclearization and see what the U.S. is willing to compromise on.

During the South Korean president’s visit to Washington, Seoul assented to the U.S. prioritizing the complete denuclearization of the Korean Peninsula. But, in truth, the governments do not agree. South Korea will likely abandon that stance at the first sign of significant tensions and ask the U.S. to make concessions. In contrast, the Japanese government will continue to advocate for denuclearization.

China will continue to look for fissures in South Korean-U.S. relations and opportunities to strengthen its influence over South Korea. This aim is becoming a priority for Beijing.

While the administration clearly wants to put Northeast Asia on the back burner now that it has settled basic policies, that is unlikely to happen. In fact, Pyongyang will probably look for the most troublesome moment to get President Biden’s attention. The U.S. is seeking to minimize foreign policy distractions through the first year of the Biden presidency, but North Korea is unlikely to comply. The administration’s first impulse in the event of a crisis will be to look for an easy way to de-escalate. That may well provide Pyongyang with an opportunity to increase its leverage.