What lies ahead for President Bolsonaro

President Bolsonaro came into office in the aftermath of a deep recession. His deregulatory reforms have shown commitment to a pro-market agenda, but he lacks popular support at the moment. His fate could be affected by the outcome of the Covid-19 pandemic in Brazil.

In a nutshell

- President Bolsonaro carried out broad pro-market reforms

- Brasilia and Washington are expanding their cooperation

- Discontent over Brazil’s handling of the pandemic is growing

Brazilian President Jair Bolsonaro rode a populist, antiestablishment and anti-corruption wave into office in late 2018. On the domestic front, he is developing short, medium and long-term economic policies to get the fiscal situation onto a sustainable path. He inherited a Brazil straight out of its deepest recession, in 2015-2016. Cleaning up the economy is at the top of the administration’s agenda, as well as restarting and stimulating economic growth. This means ramping up former President Michel Temer’s pro-market policies.

In keeping with this economic freedom agenda, President Bolsonaro and his office ushered in new deregulatory reforms in the telecommunications sector, removing protectionist hurdles that prevented foreign investment. This is expected to facilitate investment in rural areas and modernize the physical infrastructure once fully implemented. Furthermore, $23 billion in government assets were privatized. Compared to the rest of Latin America, Brazil has more than 10 times the average amount of state-owned enterprises, with 440 under government control.

The hallmark of this economic agenda was the passing of a broad pension reform bill in the fall of 2109. A recent report by Diogo Ramos Coelho of the National Association for Business Economics highlights how pensions were the primary contributor to the ratio of debt to gross domestic product (GDP) – the chief cause of Brazil’s fiscal deficit. In 2013, the ratio was 51.7 percent of GDP and by 2016 it rose to 69.9 percent. Addressing the fiscal burdens caused by public pensions required congressional legislation and a constitutional amendment. This overhaul of the pension system is expected to save Brazil an estimated $200-210 billion over the next decade.

Statesman

In the foreign policy realm, the Brazilian president has managed to balance two key relationships, with the United States and with China, pragmatically. Mr. Bolsonaro and U.S. President Donald Trump have a personal camaraderie that their governments have turned into actionable policy. Both were the antiestablishment, nationalist candidates in their respective elections and they have prioritized repairing the fractured bilateral relationship between their countries.

After nearly 15 years of strained relations, Brasilia and Washington are broadening the cooperation and resolving long-standing challenges. During President Bolsonaro’s first visit to the White House in March 2019, 17 agreements were concluded, including the 20-year negotiations to allow U.S. companies to launch satellites from Brazil’s Alcantara Launch Center. The U.S. also took the step of designating Brazil as a major non-NATO ally (MNNA), only the second in Latin America.

After nearly 15 years of strained relations, Brasilia and Washington are resolving long-standing challenges.

While President Trump has prioritized recalibrating the U.S.’s relationship with China, Brasilia has managed to maintain and expand a healthy commercial relationship with Beijing even if Mr. Bolsonaro was not always a pragmatist on Sino-Brazilian relations during his electoral campaign.

In Latin America, relations with Venezuela are a bellwether for a leader’s commitment to democracy. On this front, President Bolsonaro has reclaimed legitimacy for Brazil, which his predecessors had lost due to their close relationship with the regime in Caracas. The president has been forward-leaning in addressing the crisis in multilateral and regional forums. Like many of his regional neighbors, he does not have formal diplomatic relations with President Nicolas Maduro, recognizing Interim President Juan Guaido instead.

Shortcomings

Like his friend in Washington, Mr. Bolsonaro can be off-putting to some in the international community. As a leader, he has not learned to temper these tendencies to advance his policy agenda. During the Amazon fires, his clash with French President Emmanuel Macron almost jeopardized the European Union-Mercosur trade agreement after 20 years of negotiations.

Brazil’s homicide rates have declined but organized crime has worsened. President Bolsonaro’s tough-on-crime policies have increased the prison population. Like throughout much of Latin America, criminal organizations are running transnational networks within and outside of prisons without being prosecuted.

Brazil’s homicide rates have declined but organized crime has worsened.

Also, Brazil to date is the only tri-border country that has not designated Hezbollah a terrorist organization. Argentina and Paraguay have already taken this step, knowing their financial systems were used by Hezbollah financiers operating in the region.

Coronavirus

In late February, Brazil had Latin America’s first confirmed COVID-19 case. It continues to lead the region with nearly 30,891 confirmed cases as of April 17. The country is seriously behind the curve with the implementation of policies to prevent community spread. Over 20 members of Mr. Bolsonaro’s senior staff are confirmed to have the virus, many of which met with senior U.S. government officials, including President Trump and members of Congress.

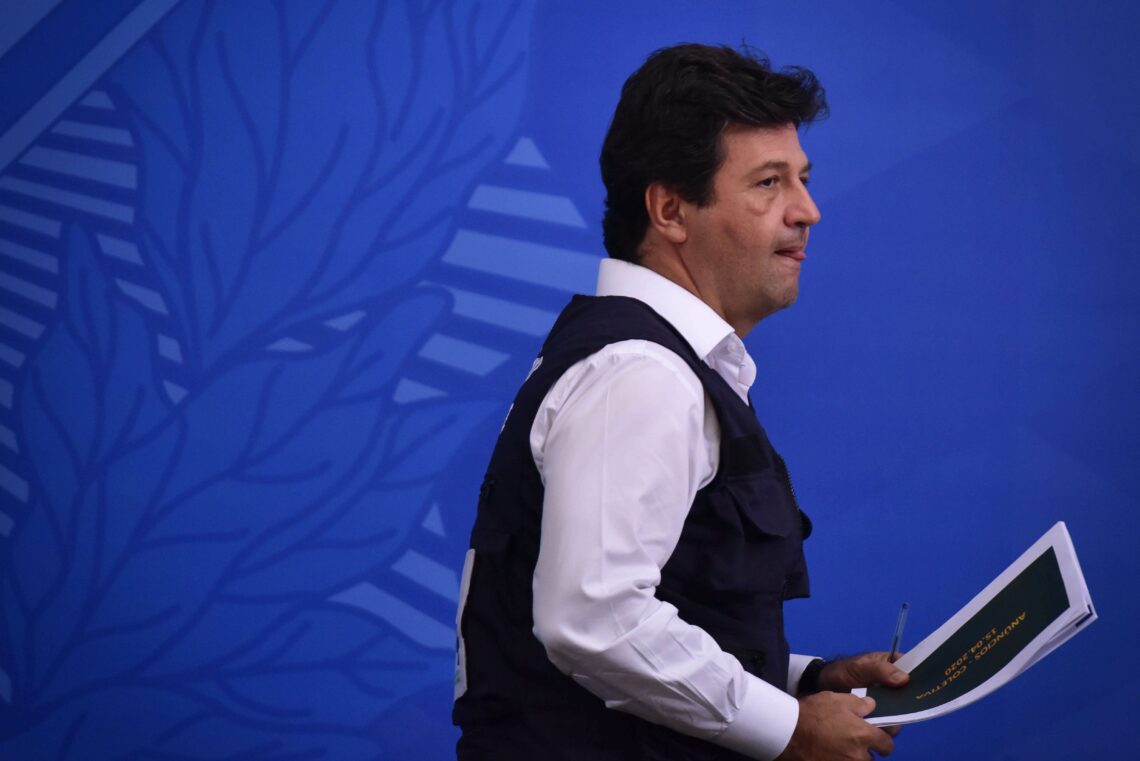

In Brazil, state governors and members of the cabinet have instead taken the lead and closed down nonessential businesses, called for social distancing and limited travel. Mr. Bolsonaro claims these measures are political attacks against him and too costly for the economy. Instead, he ignores the recommendations of health professionals and urges his supporters to participate in protests. He even went as far as firing Health Minister Luiz Henrique Mandetta. Yet Mr. Mandetta’s replacement, Nelson Teich, is a well-known oncologist whose policies on the pandemic do not differ greatly from those of his predecessor. It is still unknown how much flexibility or power Mr. Teich will be given in his new role.

Reportedly, some of Mr. Bolsonaro’s voters are growing disenchanted with his approach to the pandemic. Yet it is too early to determine how much of a political impact this will have. Brazil’s coronavirus infection rate has not yet peaked, meaning the worst is to come. The flu and respiratory disease season begins in June-July and infection rates could increase then. Population density rates in Sao Paulo, a business hub, are as high as 7,216.3 people per square kilometer, compared to 420 for the hard-hit Lombardy region of Italy.

Scenarios

Going into its second year, the Bolsonaro administration intends to expand on its economic development agenda. It plans to simplify the tax system, which has broad government and private-sector support, and to further privatize state-owned entities. An additional component of the agenda is the Economic Freedom Act, meant to improve Brazil’s business environment via legislation instead of executive actions.

Mr. Bolsonaro’s political agenda and capital depend on his handling of the economy. His management of the pandemic could eventually determine how the rest of the administration proceeds. As it currently stands, the president is falling out of favor with many Brazilians even within his base.

Mr. Bolsonaro is effective at rallying Brazilians against a common enemy. As a candidate he united his base against establishment political parties but, in the midst of a health crisis, there is little to oppose. March polling from research institute Datafolha shows approval ratings for governors who have taken a proactive approach toward the pandemic are nearly 20 percent higher than those of the president. There is growing support for impeachment. Considering former President Dilma Rousseff was impeached and her successor was nearly removed from office, this scenario should not be dismissed as mere conjecture.

President Bolsonaro is a populist who lacks popular support at the moment. This could cause irresponsible behavior and deeper clashes with federal and state-level officials who have a divergent view of how to manage the coronavirus. At worst, mismanagement could result in a deadly outbreak and an economic recession.

The coronavirus’s impact will determine the need for an economic stimulus plan from the Brazilian government. Governments around the world are spending to support unemployed citizens and Brazil only recently emerged from its worst recession. This necessary but costly measure could clash with Mr. Bolsonaro’s vision for economic freedom as a path to revival.

Irrespective of how the crisis plays out, there is a high probability the country’s tax system will be simplified in the near future. There is wide support for this measure beyond the administration. Brazil has a high consumption tax rate at 32.6 percent and a 35 percent corporate tax rate. There are also six different tax codes and each of the 26 states have their own codes, rates, and bases. A simplification and centralization plan is long overdue.

There is often talk of an imminent free trade agreement (FTA) with the U.S. in light of the close relationship between both capitals. However, an FTA is highly unlikely in the short to medium term; FTAs are not about political camaraderie. Such a deal would dismantle the tariffs and nontariff trade barriers that Brazil has developed mostly to protect revenue-producing industries. Yet the politics of trade in the U.S. are not unfavorable to an FTA with Brazil. While it may have taken the Trump administration nearly two years to renegotiate the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), it is the first trade deal to have earned support from the U.S.’s largest labor union. If Mr. Trump is reelected, there is a high probability that formal negotiations will start.

President Bolsonaro’s relationship with Israel appears at odds with his conservative values, but there is little prospect his administration will join the U.S. and move the embassy to Jerusalem. Brazil is the world’s largest exporter of halal meat to the Muslim world. An embassy move could disturb commercial ties and create an opening for competitors.

One certainty should be kept in mind. While Mr. Bolsonaro is unique to Brazil, it is safe to say he represents a reconfiguration of Brazilian politics and is part of the shift toward modern-day populism. Voters are frustrated with a political class that was unwilling or incapable of serving their needs. Constituents want a leader they can connect with on a personal level. The Brazilian president is part of the cadre of leaders who use social media to bypass journalists and bond with citizens. This is not an anomaly but a new era in world politics.