Britain will thrive after Brexit only if it dares to reform

Leaving the European Union is not enough for the UK to unleash its entrepreneur potential, boost its share in global trade and return to high growth. To bring benefits to the UK, Brexit would also need to be followed by bold liberal reforms.

In a nutshell

- The post-Brexit UK needs to make itself a business paradise

- For that, a low-tax strategy is essential

- Teaming up with the U.S. on trade will carry significant risks

Before long, Europeans will judge whether the United Kingdom’s exit from the European Union is a blessing or a curse. Generalizations are dangerous, of course, since each country has its features and leadership of varying aims. Yet, there is no doubt that Britain is going to set an instructive example.

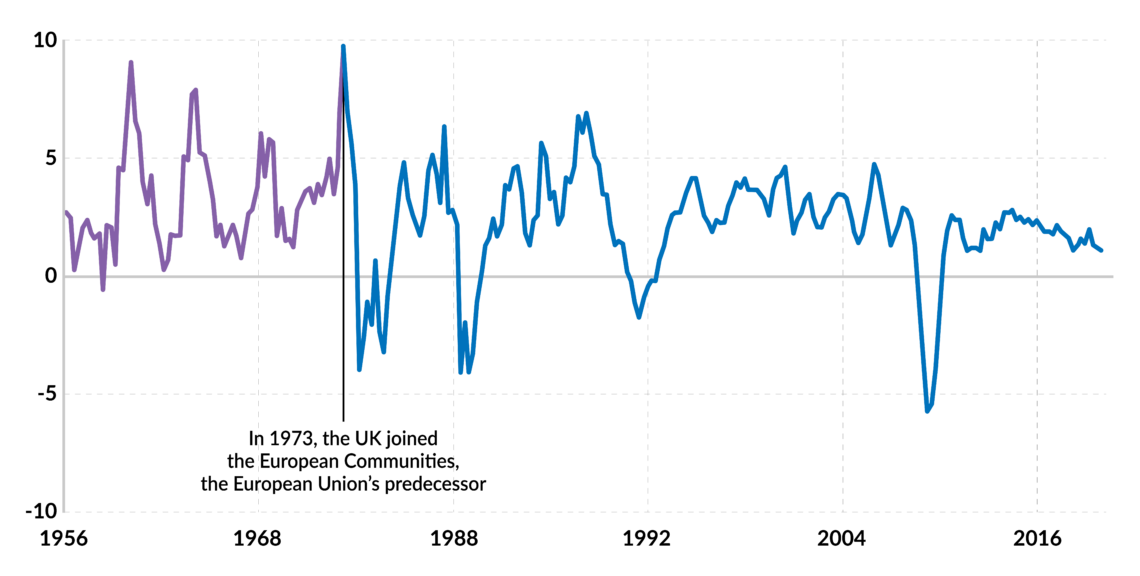

The main reason the UK has left is only partially related to economic performance. Although its annual gross domestic product (GDP) growth has been declining since 2014 and is lower than the EU average, during the past 10 years, economic expansion in the UK has not been disastrously slow (between 1.5 percent and 2 percent, with very few exceptions). The rate of unemployment is enviable at 3.8 percent, public debt (81 percent of GDP) has risen but is not a source of significant worry. Finally, labor productivity growth is similar to the rest of the EU and better than in Germany.

No common ground yet

Economic tensions between the EU and the UK are mainly due to the British believing they can do better and that the EU regulatory burden is clipping their wings. Those who supported Brexit judge that reforming EU policymaking is hopeless and that Britain outside the EU can attract more investment and make better use of its entrepreneurial energies.

On paper, such expectations are not misplaced, provided that Britain does not antagonize Brussels on trade and financial matters. The key to future British success is making sure London is a business paradise and a privileged springboard to do business with the old continent. In early January, President of the European Commission Ursula von der Leyen declared that friendly cooperation with the UK was her priority, that common values would be preserved and that she felt confident that the two sides would agree on a satisfactory deal. This may sound nice, but the real message is that not only do the two parties still need to figure out what these shared values are. Also, they need to finally agree on how to proceed.

The foremost question that the post-Brexit UK needs to address is its tax strategy.

While the European Commission wants a comprehensive deal in which each party makes concessions on some issues to win the day on others, UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson intends to proceed step by step: considering and solving one problem at a time. If he does not change his views on that, the negotiations could drag on forever. The EU would pay a substantial price, of course, but the consequences for the UK could be even more onerous.

Pitfalls ahead

Trade is a crucial issue. In theory, no one questions the virtues of free trade. In practice, it has morphed into a debate over “fair trade,” which has become a euphemism for not competing on taxation levels. Hence, the foremost question that the post-Brexit UK needs to address is its tax strategy. The UK’s flat tax rate on profits is currently 19 percent, just two points below the EU average. However, the total tax and contribution rate (TTCR) – the measure reflects pressure on business, as it includes social security contributions – is 30.6 percent in the UK and 36.6 percent in the United States, but much higher in Europe. In France, for example, it is 60.7 percent. Italy’s TTCR is 59.1 percent, Germany’s 48.8 percent and Spain’s 47.0 percent.

This is a good reason to invest in the UK. On the other hand, the country’s relatively low tax burden could be used as a basis for accusing London of “social dumping” and “unfair” competition. Indeed, when the EU insists on a level playing field, it means that the field is the current EU regulatory and protectionist framework, one of the very issues that triggered British discontent.

Can the UK buy time or possibly do without a trade and tax agreement with continental Europe? Although the U.S. is the largest single importer of British goods (more than 13 percent of British exports in 2018), the EU remains the largest importer, absorbing almost 47 percent of British exports (down from 55 percent in 2006). China takes in about 6 percent and the rest of Asia less than 20 percent. Also, 53 percent of UK imports come from the EU. By contrast, the UK imports account for about 6 percent of the exports of the EU members – 18 percent if one excludes intra-EU exports.

Put simply, Britain can hardly afford a trade war with the EU.

Scenarios

Although we shy away from providing a taxonomy of the possible scenarios, given the substantial commercial links between the UK and the EU, two sets of issues will define the economic consequences of Brexit – and ultimately show whether leaving the EU has been wise.

One set regards the baseline strategy. Are the British truly determined to pursue a free-market strategy – deregulate, cut taxation and slash public expenditure – and live with the consequences? Although overall tax pressure (total tax revenue as a percentage of GDP) is currently relatively low (34.6 percent in the UK, 40.3 percent in the EU), public expenditure remains substantial (about 39 percent of GDP). In other words, reducing the size of government is not impossible. Yet, it would take a major and widely shared ideological commitment to drive taxation (and public expenditure) down to about 30 percent of GDP – this being the threshold that is likely needed to make the UK attractive for investors, entrepreneurs and qualified workers, accelerate social mobility and transform the country into an economy radically and visibly different from the EU stereotype that most Brits apparently abhor.

The second issue regards the relationship of the UK with its single most important commercial partner. If the British want to be an active player when global policies are being discussed, they must take sides and team up with other partners. The U.S. is the only candidate as many Brexit supporters seem to be persuaded that it would make a better partner than the EU bloc.

Although the UK is probably ready to create a free-trade area with the U.S., Washington would likely require a customs union – the difference is that in the latter case, the U.S. would probably dictate the trade policy vis-a-vis third parties, and the UK would have to follow. Given the weight of the U.S. and the rather bold trade strategies enforced by the American administration in recent years, is the UK economy ready to endure the economic and political tensions triggered by its partner across the ocean? And how can the British authorities reconcile their possible free-market drive with what a new, tighter partnership would require?

To conclude, Brexit will probably not end up in a disaster for Britain. Far from it. However, it takes a lot of ideological commitment to become a free-market paradise.

The UK is far ahead of the EU bloc along this road. It is not apparent, however, that its commitment to go further is strong enough. Mr. Johnson himself, for example, has already announced that he would not roll back the size of government and that he was planning to increase public expenditure on infrastructure. This makes electoral sense, of course. The prime minister is well aware that many conservative votes come from Labour supporters disappointed with the leadership of Jeremy Corbyn, but not necessarily free-market enthusiasts.

British pride and (lukewarm) free-market spirits will probably keep the British economy going and show that one can leave the EU without catastrophic consequences. However, Brexit will also show the current EU members that leaving may be a source of unexpected problems rather than easy solutions.