What a swell party this is

Political parties in Britain have been fading in the 21st century in terms of membership, popular support and relevance to citizens. To many, traditional parties seem more a part of the problem than the solution. Can parties be salvaged?

In a nutshell

- The role of political parties in Britain has been fading rapidly in the 21st century

- Just 1 percent of Britons describe themselves as active members of a political party

- Social media is a poor substitute for direct, grassroots political activism

In 1936, Cole Porter came up with a song that included the engaging lyric “what a swell party this is.” And while people enjoyed Cole Porter’s “have a good time” parties, the soberer political parties were generally regarded as swell things to be a part of too.

In the mid-1930s, Britain’s Conservative and Unionist Party had around one million members, rising to 2.8 million by the end of World War II and the Labour Party, with a membership of half a million, saw its membership double during the same period. Moreover, Labour could call on mass membership of trade unions and the affiliated Co-operative and Socialist parties – peaking at around 5-6 million people.

In the post-war period, membership of political parties in Britain increased further. They were organized at the grassroots level – right down to street captains who would collect membership subscriptions and use the parlors in their homes as committee rooms on election day. Paid constituency agents kept the party’s local association in good order. They ensured that the member or candidate was abreast of all the local issues and news, and the vote gathering machinery well-oiled and always ready to contest local and national elections.

Cole Porter would certainly have approved of the social side of the local political party. Fundraisers, gala dinners, wine and cheese parties, coffee mornings and the rest were events where people of similar views would meet. The youth wings were famous for the marriages which blossomed from social events, door-to-door canvassing, and electioneering.

Joining a political party was seen as a civic virtue while the duty to vote, and to participate, was imbibed with your mother’s breast milk – not surprising, as millions had just fought a war to preserve democracy against Nazism. And it was still within the living memory of many that half the population – women – had been denied the vote. It had taken until 1928 for women and men (over the age of 21) to have full electoral equality.

By the turn of the 21st century, Cole Porter’s swell party didn’t look so swell anymore.

Those who had campaigned for the franchise had not forgotten Emmeline Pankhurst’s clarion call to her protesting suffragettes: “We are here, not because we are law-breakers; we are here in our efforts to become law-makers.” Voting and being a member of a political party was a badge of honor – and a right won with blood, sweat and tears.

But memories are notoriously short. With the fading recollection of the sacrifices and price paid to secure the right to vote, participation and membership of political parties began to ebb away. Simultaneously, the admiration and respect in which the political classes had been held have been increasingly replaced by distrust and a negative view of politicians who put their self-interest before public service.

By the turn of the 21st century, Cole Porter’s swell party didn’t look so swell anymore. Significant falls in membership numbers showed that the political parties were partied out. Between 2002 and 2013, Conservative Party membership, already depleted from its halcyon days of nearly 3 million members, fell by more than half from 273,000 to 134,000. The party says that if you include “activists” rather than members, the number is closer to 500,000.

Labour has experienced a similar decline, with membership at 485,000 in August 2019; the Scottish National Party (SNP) at 125,000; the Liberal Democrats at 115,000; the Greens at 48,000; and Plaid Cymru (which advocates Welsh independence) at 10,000.

In the same period, the UK Independence Party had 29,000 members, while the Brexit Party of Nigel Farage does not have members but lists 115,000 registered supporters. There are also small political parties in Northern Ireland, but this puts total membership of the UK’s political parties at around 1 million people. As a percentage of the UK’s population of nearly 68 million, this is a vanishingly small number.

So, should the parties be worried?

Party organizers should be concerned that across the principal parties (Conservative, Labour, SNP and Liberal Democrat), the average age of members is in the mid-50s; that the number of people from racial and ethnic minorities is low, between 3 percent and 4 percent; and that most members belong to the highest social class. Apart from the Scottish National Party, most party members live in the south of England (excluding London). According to the 37th British Social Attitudes Survey, two-thirds of citizens no longer identify with a political party.

Only 1 percent of Britons declare themselves active party members.

Party managers dismiss the decline in membership by suggesting that it is a trend that is affecting everyone, complacently suggesting that “no one joins anything anymore.” But that is simply not true.

According to the Hansard Society, only 1 percent of Britons describe themselves as active members of a political party. Compare that with the 26 percent who say they are active members of a sports, leisure or cultural group; the 12 percent who are part of a religious group; and the 12 percent who are part of a voluntary organization.

Compare the active participation in political parties with the 5.6 million members of the UK’s National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty (founded in 1895 and with a membership bigger than the population of Finland), or the Scouting Movement (founded 1908). Some 49,000 people are involved in scouting activity every week in the UK and it has a thriving youth membership of 391,000.

The Caravan Club (founded 1907) has nearly 1 million members; the Royal Automobile Club (founded 1897) has 8 million members. The Women’s Institute has 220,000 members in 6,300 branches; the Freemasons have 200,000 members in 6,800 lodges, while 2.6 million people attended Christian services last Christmas. And although church attendance has declined, the political parties should be envious of the 25 million people who identify as members of the Church of England and 5.2 million as Roman Catholic.

So, it simply is not correct to say that people are no longer willing to identify with organizations or to become active members. However, the parties can take some comfort from how political activism has crossed over into campaign groups and into the virtual world. A low-profile campaign group, such as the Council for the Preservation of Rural England, says it has a presence in all English counties, with 40,000 members in 100 district groups. It generates nearly GBP 1.5 million annually in membership subscriptions.

At the other end of the spectrum, Greenpeace employs 100 people in a former animal testing laboratory in North London and campaigns exclusively around environmental issues. The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament, the National Council for Civil Liberties, Human Rights Watch and the European Movement are just some of the many other campaign groups that interface with political parties and help shape their manifestos.

Their activists often end up standing for elected office just as people drawn into local campaigns, defending local amenities, find themselves elected to a local council and then drawn from community politics into party politics. Party managers have a point when they say that political activism, especially among the young, is now found on the internet, across social media. Undoubtedly true. But herein lies another problem.

Political parties in Britain and the world are the engine room of our democracies and we should be genuinely concerned when they become dysfunctional.

Sitting with a tablet, a phone or a computer, sending off messages via Facebook, Twitter or Instagram, is not the same thing as knocking on doors and engaging directly with people. If lockdown has taught us anything, it is surely the limitations of one-dimensional zoom meetings compared with three-dimensional human interaction. The political parties in Britain and elsewhere spend millions on social media messaging, but it is not the same as being close to the people.

Does any of this matter?

It might be tempting for this writer, sitting as an independent in an unelected upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom, to repeat the lazy, somewhat sneering, remark that party politics is a dirty business; that the parties have brought decline on themselves and that it serves them right.

But this would not only be lazy, it would contribute to spreading a dangerous canard. Political parties in Britain and the world are the engine room of our democracies and we should be genuinely concerned when they appear to be dysfunctional or increasingly unable to inspire the public to speak well of them, let alone join them.

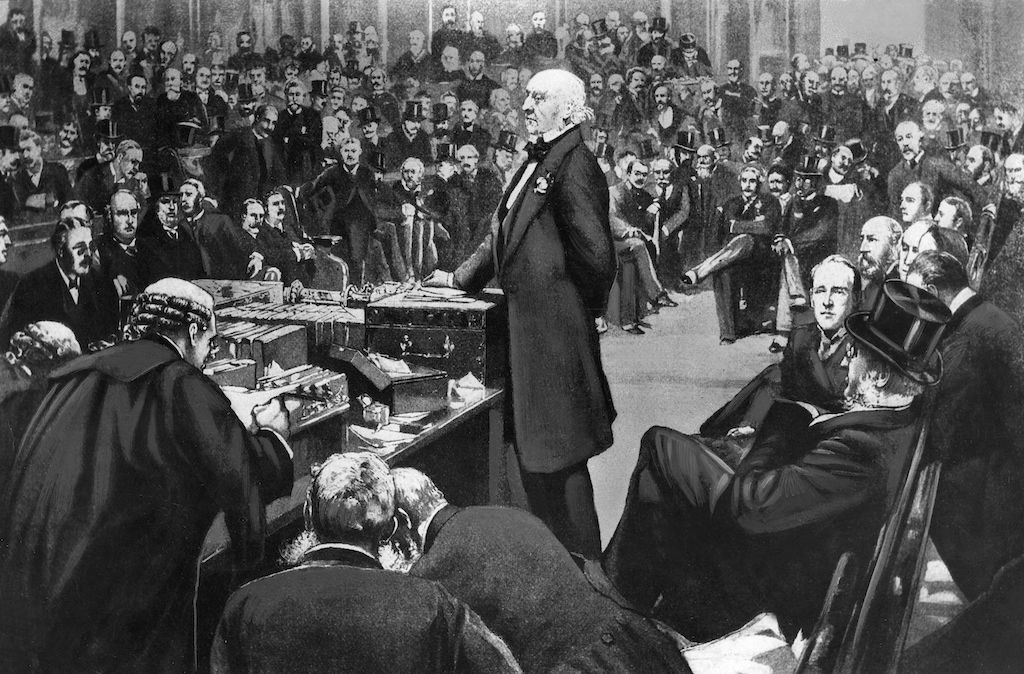

As a teenager, I joined a small political party that could trace its origins back to the heady Victorian governments of William Gladstone (1868-1894). A century later, it had just a handful of MPs – all from the UK’s Celtic fringes – and pollsters said it enjoyed less than 5 percent of the popular vote. But the idealism, honesty and courage of its thoughtful leader, who told us to “march into the sound of gunfire,” inspired me to join. But it would have been a bad move if I had simply wanted a career in politics.

Instead, it exposed me to ideas and like-minded people. It provided friendship and camaraderie and, having heard the gunfire and seen the acute needs of an impoverished neighborhood in the inner city of Liverpool, it saw me elected as a city councilor, and, for 18 years, as a member of parliament. During those years, I served as president of its youth movement, as chair of its policy and candidates committees, as its chief whip, and as the party’s national spokesman on a range of issues. After 30 years of membership, a well-publicized disagreement over an issue of conscience led me to leave my party. But I have never changed my mind about the central importance of political parties to our democracies. It disturbs me to see their decline.

How must political parties act to renew themselves?

The parties that remain relevant – and still “hear the gunfire” – are the ones that will survive. Those that become hostage to the tiny numbers of people who now own the parties – and impose increasingly irrelevant fringe ideology as their central message – will decline and disappear. They deserve to. New ones (and renewed old ones) that owe more to political courage than political correctness will emerge. Movements and alliances will morph into factions and coalitions, and they, in turn, will become the parties of government. There is nothing new in that.

Today’s political parties have their genesis in the struggles of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In the United States, the fight over the federal constitution of 1787 gave birth to factions that morphed into political parties – defined mainly by their differing views on where power should reside. In the United Kingdom, the Conservative Party, Britain’s oldest political party, emerged in the 1830s from the Tory factions that upheld “Throne, Altar and Cottage,” reinventing itself in 1834, as parties invariably do, when Sir Robert Peel issued his Tamworth Manifesto setting out the principles of Conservatism.

Quickly demonstrating how vulnerable political parties are to roller-coaster issues, the Conservatives were soon split.

But also, quickly demonstrating how vulnerable political parties are to events and roller-coaster issues, the Conservatives were soon split over the Repeal of the Corn Laws, with protectionists retaining control of the party. Many of the Peelites drifted into an alliance with some Whigs and Radicals, ultimately forming the Liberal Party in 1859. The political theater’s changing scenery constantly leads to new plays, new performances, and new players. In the nearly two centuries that have followed, the Conservative Party’s early splits have been mirrored right across the political spectrum.

Gladstone saw his Liberal Party split over home rule for Ireland (with Liberal Unionists joining the Conservatives). In 1900, the Liberals’ failure to speak for the industrialized masses led to the birth of the Labour Party. Its uneasy coalition of Socialists and Social Democrats – evident to this day – led, in 1981, to Labour’s rupture and the center-left realignment that gave birth to the Social Democratic Party (SDP). That was eclipsed in 1994 when Tony Blair reinvented his party as “New Labour” and by 1988 the SDP had morphed into the Liberal Democrats.

Political parties can change beyond recognition – but when they fail to evolve or to read the signs of the times, they can face annihilation. In 1935, George Dangerfield published his Strange Death of Liberal England, which described how a political party can ruin itself by combining incompetence and irrelevance. A sequel might examine the strange death of the Labour Party in Scotland – where, having been the preeminent political force for generations, it won just one of Scotland’s 59 seats in the House of Commons in 2019.

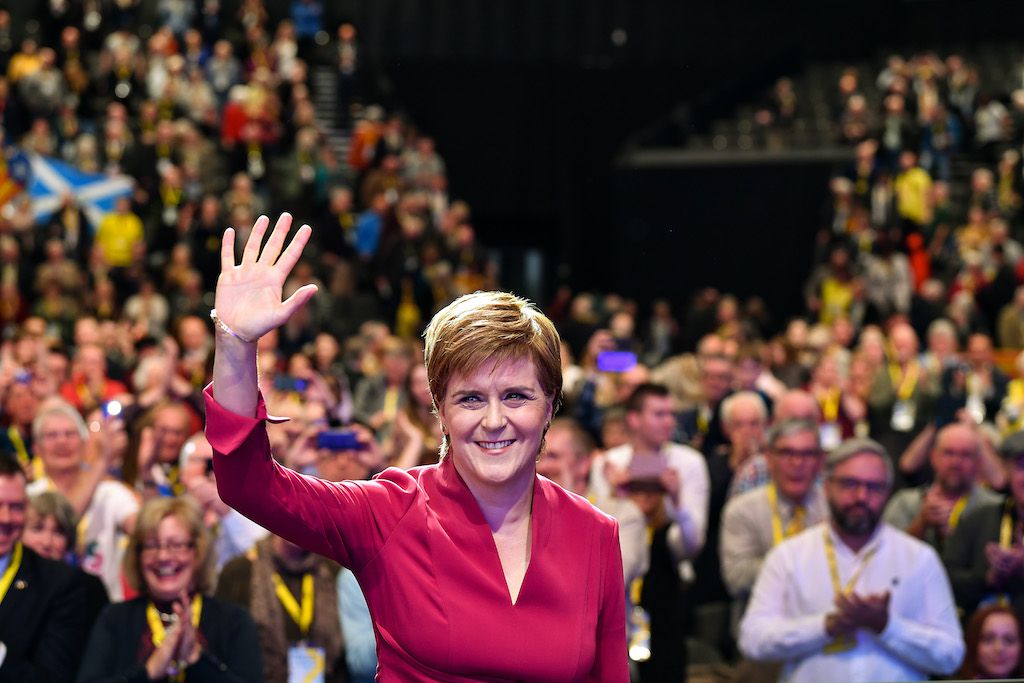

Meanwhile, the Scottish National Party (now the UK’s third political force) has 47 representatives (MPs) in the UK Parliament, 61 members of the Scottish Parliament and 418 local councilors. Its effectiveness at the grassroots, its general level of competence, and its care not to overly trample on its members’ consciences, have enabled it to build significant support for its campaign for independence. Its success as a political party has been assisted by the woeful inadequacy of its Scottish political counterparts.

Perhaps the most important part of the UK’s unwritten Constitution is ‘Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition’.

More than anywhere in the UK, Scottish Labour relied on the tribal votes of supporters whose families had always voted Labour. It had failed to notice that one of the most striking trends in recent decades has been the diminishing number of people who say that they have tribal loyalty to any political party. The latest survey of British Social Attitudes (October 2020) found that just 7 percent now feel “very strongly” attached to one of the country’s political parties.

The truth of that was vividly illustrated by the collapse of Labour’s Red Wall seats (traditional Labour constituencies across the north of England), taken in the 2019 General Election by Boris Johnson’s Conservatives. That landslide was further evidence of how traditional party loyalty has been diluted – and undoubtedly accelerated by incumbent political parties’ tendency to contemptuously treat seats as “safe” and take their voters for granted. Labour was also handicapped by having a leadership that was gravely out of touch with the voters.

In 2019, there was a further factor at work – the polarizing effect of a crucial issue: to remain or to leave the European Union. Revealingly, in the Social Attitudes Survey, 45 percent said they were either “very strong” Remainers or “very strong” Leavers. Inevitably, such firmly held views, reflected in the results of the EU Referendum and Brexit General Election, significantly changed the political map of the House of Commons – with a Conservative Party majority of 80 and Labour’s worst result since 1935.

The result has redefined party allegiances and the relationship between the parties and the communities that voted for them. The test now will be whether the Conservative Party can represent the needs of northern voters – not just the leafy suburbs of the Home Counties – and whether Labour, under the leadership of Sir Keir Starmer, can regain the trust of voters.

Perhaps the most important part of the UK’s unwritten Constitution is “Her Majesty’s Loyal Opposition.” When a political party is seen as neither being loyal nor capable of opposing, it will never be judged capable or worthy of governing. Equally, when the principal opposition party is hobbled, the governing party will become idle, arrogant and worse – because it believes its opponents to be unelectable. That is dangerous for a democracy.

Political parties in Britain are never going to be the Communion of Saints, but we need them to make democratic politics work. If they did not exist, we would soon invent them. This is why parties must renew and reinvent themselves and why it matters if they are failing to connect or unable to attract able and dedicated people into their ranks.