EU-China investment treaty: Small win, big losses

As 2020 was drawing to a close, the Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI) between China and the EU was hurriedly concluded. At first glance, the agreement seems like a success – but it is not without risks for European businesses.

In a nutshell

- The EU has rushed to agree to an unrealistic deal

- European firms will benefit from Chinese markets

- However, Beijing is unlikely to change its ways

After difficult negotiations, an agreement on the European Union-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment (CAI), was hastily reached in December 2020, when the German presidency of the EU Council was coming to an end. On the surface, the Union appears to have gained what United States President Donald Trump could not. However, many details indicate that future goals may not be met.

Rushed agreement

It was one of German Chancellor Angela Merkel’s most sought-after goals to close the CAI deal during her country’s EU presidency. She has long emphasized that Sino-European relations must become a priority for Germany and the EU, and in this sense, the agreement did satisfy her ambition. The Union now recognizes China’s importance not only in the realm of trade but also in terms of political influence.

For the chancellor, the conclusion of the CAI was a strategic victory, the icing on the cake of the German presidency. The feat partly consisted of convincing France to cooperate. The agreement is, after all, an EU-China deal. Germany may be the engine but it is not the entire train.

It is true that more access to Chinese markets could benefit EU companies in the short to medium term.

EU leaders hurried to conclude the deal because they believe China is facing an unfavorable international environment, the worst since the 1990s. Under such circumstances, they reasoned, they could demand more of Beijing. The EU’s assessment is correct; there is an opportunity there. But it would likely not have been lost by waiting a little longer – say, until after U.S. President-elect Joe Biden’s inauguration.

Jake Sullivan, U.S. national security advisor-designate of the incoming Biden administration, warned against the agreement. Belgium and the Netherlands voiced concerns about China’s human rights record. Other member states, like Poland, expressed worries that relations with the U.S. would be damaged. An open letter signed by 15 European scholars raised doubts over the deal. Nevertheless, Ms. Merkel’s impatience rubbed off on other leaders, and negotiators went ahead.

Facts & figures

The EU, like Germany, is concerned with boosting the economy, especially because of the pandemic. The Union’s official statement on the CAI is reassuring: the treaty with China is a success story because it increases market access for European investors and addresses issues such as forced technology transfer, opaque subsidies and state-owned enterprises. It also includes Beijing’s promise to “work continuously” toward joining the International Labour Organization and abandoning forced labor. All of these elements had eluded President Trump despite his heavy-handed approach.

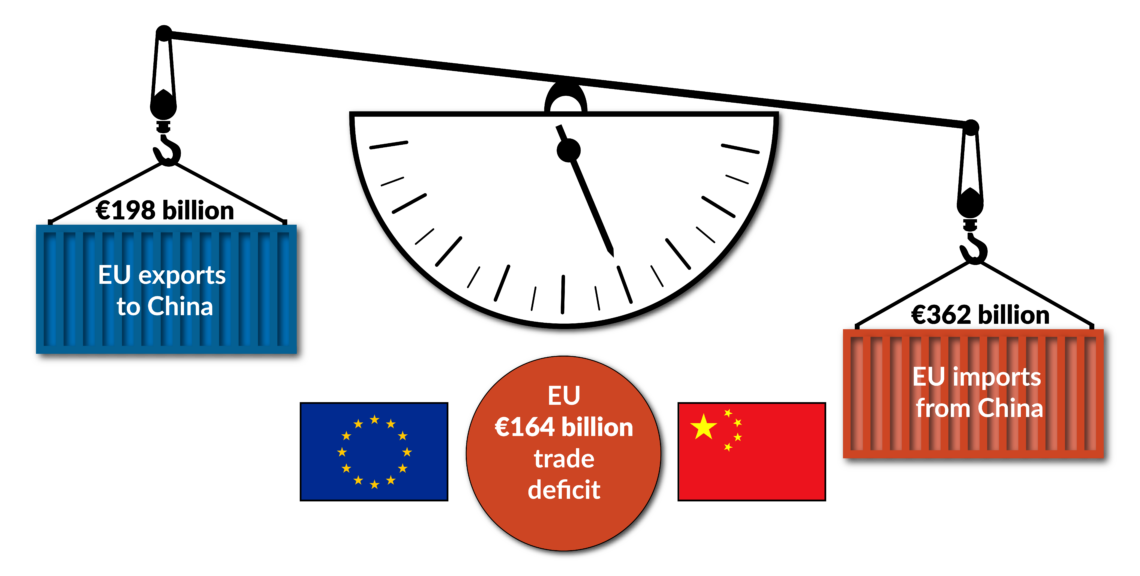

It is true that more access to Chinese markets could benefit EU companies in the short to medium term. Looking at the trade deficit between China and Europe, the Union is faced with a problem somewhat similar to the one President Trump attempted to tackle during his trade conflict with Beijing. The EU hopes the deal will indirectly reduce this imbalance.

China’s perspective on the CAI

From a macroeconomic perspective, Beijing believes European industry and capital need China more than China needs them, especially now that its economy is already recovering while Europe is still in the grip of the Covid-19 downturn. The vulnerability of the European automotive industry and German manufacturing is evident. One of Chancellor Merkel’s top priorities in Sino-German relations is to allow companies like Daimler and Volkswagen to have a stronger position in China.

Chinese authorities believe any demand made by the EU will be undercut by the latter’s economic vulnerability. The political elite has been trying to divest European business circles from politics and encourage prominent companies to pressure EU executives into taking a softer line on China.

Chinese political elites remain convinced that Western investment will lead to technology spillovers.

By partnering with the EU, Beijing is also attempting to leave Washington out in the cold. And in fact, China has now replaced the U.S. as the largest trading partner of most major economies in the world. ASEAN has also surpassed the EU as China’s largest trading partner. China-EU trade relations are still expanding. This year, China outranks the U.S. in trade with the EU, with 480 billion euros in two-way trade through October. However, with Brexit, the pastures on the EU side will be less green than before. All this has given the Chinese government a confidence boost.

As for the timing of the deal, China believes that the EU does not entirely trust the Biden administration. On the basis of this assumption, it has made several bold moves, ignoring EU criticism of its human rights situation. “Unfriendly European delegates” were denied access to the Fourth China-Europe Trade Forum, leading to the event’s cancelation. And while the CAI was being negotiated, the Chinese government publicly convicted citizen journalist Zhang Zhan for documenting the Covid-19 outbreak in Wuhan as well as 12 Hong Kong youths who tried to flee to Taiwan.

President Xi Jinping knows that the survival of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) hinges on three undertakings. One is to secure China’s dominance in emerging cutting-edge technologies, so that the country can gain a considerable share of the global market, as Huawei has done with its 5G network. The second is to keep strengthening state-owned enterprises so that they can provide a solid foundation for the national economy. And the third is to keep expanding the Chinese share of the world market, for example, via the Belt and Road Initiative, creating wealth with high-tech products. These three goals are the core of Mr. Xi’s economic policy.

China has now become the 14th leading country in the world in terms of technological innovation – the only middle-income country in the top 30. Of course, this would have been impossible to achieve without the help of Western companies and governments. But now, the global technology leader, the U.S., has caused unprecedented difficulties for China’s technological progress during President Trump’s term in office. Many key technologies are still in the hands of the West, especially American firms. In the absence of foreign investments, it would be extremely difficult for Beijing to maintain the status quo; the threat of lagging behind in cutting-edge technologies looms large. Collaborating with the U.S. has turned out too challenging. Beijing now eyes the European Union, Russia and other powers.

Room for maneuver

Cooperation requires concessions. Beijing realizes that it is no longer feasible to trade market access for technology transfer, like it did with high-speed rail or wind power technologies in past decades. Political elites remain convinced that Western investment in China will automatically lead to technology spillovers. If such spillovers fail to materialize to the extent Beijing hopes for, it can still secretly apply various means of misappropriating foreign know-how. Grand plans like Made in China 2025 and China Standards 2035 are all based on such considerations.

The EU was complacent after signing the deal, thinking it achieved what President Trump could not do. But it is too early to be happy. Take China’s state-owned enterprises as an example: Beijing does not recognize the World Trade Organization’s procurement agreement because it wants to grant them more room for maneuver. To boost them is a top goal of the Xi administration, and will remain so. Even if the Chinese side promised to rein in its nationalized companies, it is nearly impossible that their privileged status will change.

Accordingly, the European Commission’s claim that “the EU-China comprehensive investment agreement will be the first agreement to fulfill the obligations of state-owned enterprises and the rules of full transparency of subsidies” is naive. There is no reason for the EU to think that Chinese state-owned enterprises will begin to fully abide by the rules.

If the EU maintains its optimism, the biggest winner of the deal will be Beijing.

In short, if the EU maintains this baseless optimism, the biggest winner of the CAI deal will be Beijing. President Xi will have demonstrated to challengers within his own party that only he can secure China’s development on the world stage. And this kind of victory will, at least domestically, minimize the impact of the CCP’s loss of reputation due to the National Security Law in Hong Kong, disputes in the South China Sea and the irresponsible handling of the coronavirus outbreak.

Scenarios

It is highly doubtful that the EU’s political elites and companies will have the capacity to effectively counteract China’s sleight-of-hand tactics in the future. Mr. Xi will not abandon his ambitious plans in exchange for an investment deal with the EU. However, to achieve these aims, sensitive technologies from the West remain urgently needed. Obvious attempts at forced technology transfer are unlikely to continue bearing fruit, but China will develop other schemes to acquire the technologies its firms and research centers need.

Since there are no specific provisions on inspections and sanctions in the agreement, the Chinese side will have ample opportunity to breach the treaty’s well-intended but somewhat unrealistic demands. This, however, will hardly be visible in the next five years. European businesses will grow and jobs will be created. The EU might benefit from the CAI for a while.

Risks for the European Union

Nevertheless, the hasty agreement creates two risks for the EU. The first is that the EU Parliament may refuse to ratify the document on the grounds that it does too little to deter China from human rights abuses. This would lead to tension between the “moral camp” represented by parties like the Greens, and the profit-oriented industry lobby. The treaty will have to be approved during the French presidency of the European Council in 2022, potentially challenging Paris.

If the agreement comes into force, the second risk is that China will develop even more sophisticated methods of appropriating technology from rival Western companies – an eventuality to which the industry seems blind. In a decade or so, with the “unintended assistance” of European companies, China could land ahead of Europe in the technology race, at least in some key sectors.