Why they migrate

Discussions of migration from Central America into the U.S. tend to lump the principal countries of origin – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – into a single subregion, the Northern Triangle. Different push factors operate in each country, and without taking it into account, international aid will not reduce the migrant flow.

In a nutshell

- U.S. aid will help curb migration from Central America only if it is properly targeted

- In Guatemala, ethnic tensions and political corruption need to be tackled first

- In El Salvador, rampant violence can be curbed by supporting civil society

- International pressure could help Honduras replace an illegitimate government

In dealing with the inflow of migration from Central America, which has caused such a stir in the United States and even led to a government shutdown, the reporting and public discussion has lumped the principal countries of origin – El Salvador, Guatemala, and Honduras – into a subregion known as the Northern Triangle. There are significant similarities among the three states, as GIS reporting has made clear. Treating them as a unit was convenient, if not strictly accurate, in writing about the headline-grabbing “caravan” that marched the length of Mexico in the last two months of 2018 before reaching the U.S.-Mexican border at Tijuana, where most of its members remain encamped in temporary tents, awaiting their fate. A new caravan is still moving out of Honduras, through Guatemala and along the length of Mexico.

Policy responses to the caravan have reinforced the tendency to deal with The Northern Triangle countries as a single unit. From the U.S. perspective, building a wall is intended to keep everyone out, no matter their country of origin. At this writing, the wall does not appear to be winning support from the congress. On the other hand, Mexico’s new president, Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador (AMLO); the presidents of El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras; and experts throughout the hemisphere are calling for a new aid program addressing the social and economic problems that help cause migration from the region.

Providing aid to these Central American countries will only help, however, if it is tailored to the specific push factors in each country, which differ in very important ways. Without taking these distinctions into account, no amount of financial assistance is likely to reduce the migratory flow. If the aid is targeted correctly, its effect would be multiplied in all three countries by faster economic growth, which is already averaging close to 3 percent per year.

Of course, the effect of any aid program depends on how the U.S. economy fares, including remittances of immigrants working in the U.S. These financial flows can be as high as 17 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) in the case of El Salvador. Sustained growth will also require more foreign investment, which will be impossible to attract without a stable government and at least a modicum of accountability.

Guatemala: ethnicity

In Guatemala, the push factors with peculiar salience are ethnicity and corruption. Alba R. (her name is withheld to protect her privacy), a naturalized citizen of the U.S., fled her village in 1982 to escape the massacres of indigenous people during the presidency of Efrain Rios Montt. At the time, there was a widespread insurgency in the country, part of the civil war that lasted from 1960 until 1996 and claimed over 100,000 lives.

Mr. Rios Montt and his fellow senior officers in the military considered the indigenous peoples, who together with rural mestizos constitute more than half the country’s population, an “internal enemy.” More than 400 villages in the Chiche region were destroyed by troops. Alba and her family fled because her husband, a schoolteacher, had been threatened by government agents. Alba’s daughter graduated with honors from Harvard College a few years ago and, after getting an MBA from the University of Chicago, is now pursuing a career in banking.

Facts & figures

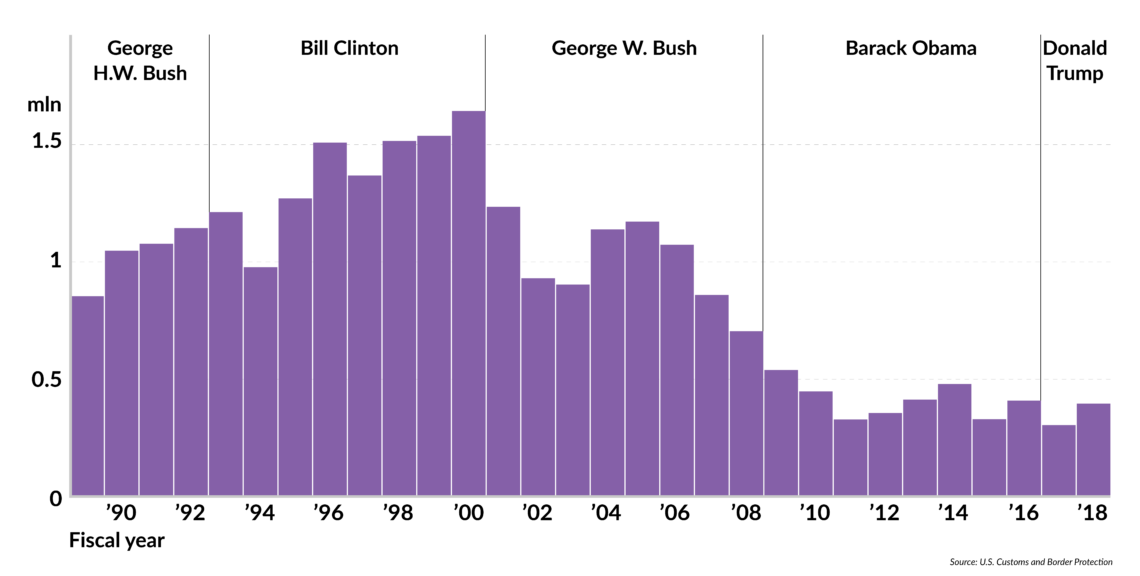

Arrests for illegal border crossings from Mexico

Guatemala’s demographic profile and its historical legacy of ethnic discrimination set it apart from the other Northern Triangle countries, which all suffer from poverty and a lack of economic opportunity. If Guatemala is ever to take full advantage of its rich resource endowment and the advantage offered by the free trade agreement with the U.S., better public services, especially education, must be made available to the indigenous peoples. Only in this way can the economic playing field be leveled and unemployment reduced, opening opportunities to a wider segment of the population. Under the current favorable trade conditions, significant expansion is possible in the coffee, truck farming and textile sectors.

Guatemala: corruption

The second factor that has significant weight in the decision to leave Guatemala is the corruption that plagues the state at the highest levels. So entrenched is the self-enrichment mania of those who govern the country that a small group of reformers pushed the government in 2006 to accept an invitation from the United Nations to create a national anti-corruption and impunity commission (CICIG in Spanish). The UN appointed a Colombian jurist to head the commission and secured funding from the UN, the U.S. and some European countries. The involvement of the international community, including civil society organizations that played a key role in the peace process in the 1990s, is important in understanding the dynamics of policymaking in Guatemala.

Guatemala’s attorney general has exposed President Morales as an even bigger thief than his predecessor.

Over the past decade, CICIG has expanded the capacity of the Guatemalan judiciary to investigate and expose corruption. Working together, these institutions ousted the previous president, Otto Fernando Perez Molina (2012-2015) and his vice president for running a customs racket. The current president, “Jimmy” Morales, a TV personality with no previous political experience, ran on an anti-corruption platform.

Now, however, Guatemala’s attorney general, armed with CICIG research, has exposed President Morales as an even bigger thief than his predecessor. Most of his dirty money came from illegal campaign contributions. The president has also been receiving a $7,000 monthly “responsibility bonus” from the military in addition to his salary. Mr. Morales’s party, The National Convergence Front (FCN-Nacion), was formed by ex-military officers as a political shield against prosecution for crimes committed during the civil war. For the past year, President Morales has been trying to expel the chief of CICIG, the Colombian jurist Ivan Velasquez, from the country and shut down the commission.

Facts & figures

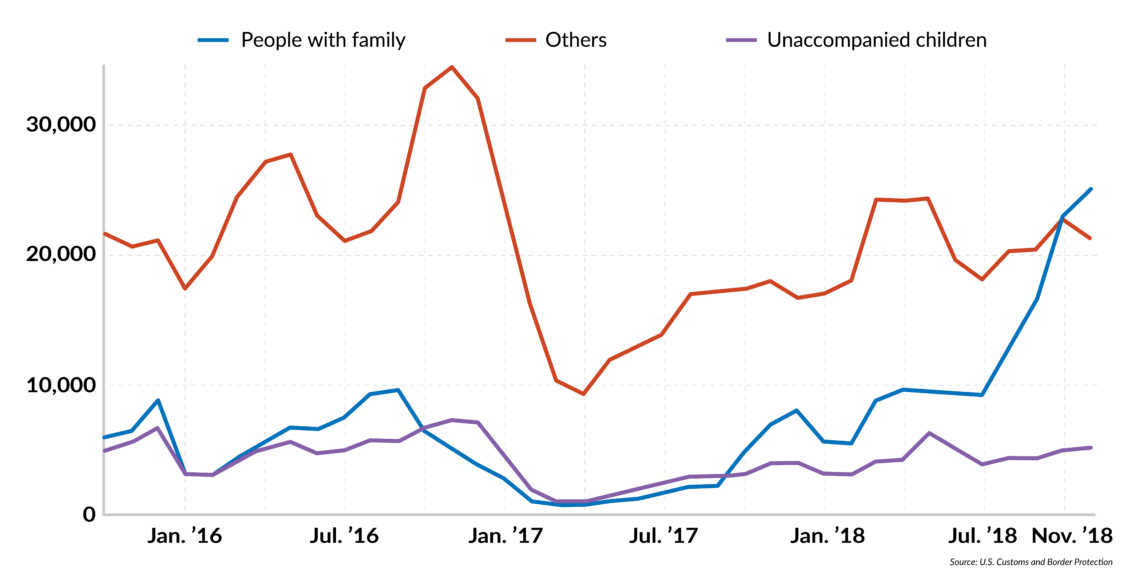

People arrested for illegally crossing from Mexico

The evidence against Mr. Morales and his family has been leaked to the press. His brother and his son have been indicted. Now, the attorney general wants Congress to lift the president’s immunity, so that he, too, can be indicted. While the political battle goes on, the government is at a standstill. Investment is on hold and the tourist industry is suffering. These knock-on effects show why any attempt to reduce migration, if it is to be effective, must buttress Guatemala’s political institutions, especially the judiciary.

The Trump administration indicated in December that it will stick by President Morales because he is an important ally in the battle against drug trafficking. That is a strange argument for abandoning CICIG, since corruption at the highest levels is what allowed the violent Mexican drug cartel, Los Zetas, to establish a safe zone in northern Guatemala to facilitate drug shipments to the U.S. If Mr. Morales wins and kicks CICIG out, there is little hope that the conditions driving Guatemalans to emigrate will ease.

El Salvador: violence

The issues in El Salvador and Honduras appear similar to those in Guatemala, yet differ in ways that require a distinct policy approach. In the case of El Salvador, the core problem is violence. In some sense, the U.S. government has acknowledged this fact by singling out the MS13 gang (Mara Salvatrucha in Spanish), which has also been active in the U.S. Gang members pass back and forth between the U.S. and El Salvador using normal modes of transportation, especially air travel. That makes a wall useless in combating MS13 and other violent gangs.

Almost half of Salvadorans interviewed at the U.S. border report that gangs have threatened a family member.

Through the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID), there are already programs in place to tackle the most pressing issues. The difficulty is not in understanding the situation, but in making sufficient resources available to deal with it. Efforts are underway to professionalize the Salvadoran police and make them more effective in combatting violent crime. There have been minor successes, but as the testimonies of ordinary people make clear, the results are inadequate. Nearly one in two residents of San Salvador, the country’s capital, reports having been the victim of a violent crime. Almost half the Salvadorans interviewed at the U.S. border over the past month report that a family member has been threatened by a gang member. Personal safety is the heart of the matter.

Another USAID program that could help curb emigration if more funding were made available promotes civic awareness and political participation. Most recently, in El Salvador, the money has been channeled through local universities to set up monitoring of the February 2019 presidential election. The sums involved are trivial – in the hundreds of thousands or a few million U.S. dollars – compared to the billions required to build a wall or beef up U.S. border security.

One of the legacies of El Salvador’s 20 years of domestic conflict is that civil society is organized to a degree not found in other countries that have experienced large out-migrations, such as the Middle East or Africa. Civil society in El Salvador is even more highly developed than in the other countries of the Northern Triangle. If these groups were supported, it would immediately alleviate the forces pushing Salvadorans to emigrate.

Honduras: illegitimacy

In Honduras, the core problem is the illegitimacy of a government tied to drug trafficking. Criminal violence in Honduras is even more widespread than in El Salvador. The murder rate in the country’s second city, San Pedro Sula, is the highest in the hemisphere. Unlike El Salvador, however, a policy response focused on the violence would be the wrong place to begin. The Honduran government’s lack of accountability and the miasma of corruption that envelops it are the principal issues that must first be addressed by any policy seeking to curb emigration.

The place to start is by pressuring President Juan Orlando Hernandez and his government, who stole the November 2017 elections, to hold a new general election with sufficient outside observers. There is no alternative but for the U.S. to take the lead. The Trump administration’s continued support for the Hernandez government defeats its other policy efforts to reduce the flight out of Honduras.

The Organization of American States (OAS) has already indicated its readiness to help monitor a new ballot. Once reasonably honest elections are held, the U.S. and the OAS must then insist that the new government work to eliminate the corruption and organized crime that make life for the citizens of Honduras unbearable. Only then can other programs begin dealing with the social and economic causes of emigration.

Outside help

All policy options to reduce the flow of migrants from the Northern Triangle require effort by the U.S. and the hemispheric community. Both have already had a powerful effect in these countries, which cannot be expected to clean up their internal governance on their own. In all three countries, the weakness of state institutions and the lack of popular trust in the state must be taken into account.

The U.S. can do several things to better control the migratory flow – none of which involves building a wall.

In addition to providing dramatically increased financial support to El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, the U.S. can do several things to bring the migratory flow under better control – none of which involves building a wall. First, it is important to recognize that the problem cannot be solved unilaterally. The U.S. needs Mexico as a partner to reduce pressure at the border.

The short-term challenge, with or without a wall, is to improve the effectiveness of border control. There is a desperate need for more U.S. customs and immigration officers to deal with the pent-up demand for asylum hearings from residents of tent cities on the Mexican side of the border. Spending on surveillance technology could also be a more cost-effective way to improve border security.

All these responses are politically feasible under the current administration and would go a long way toward relieving the sense of crisis that is roiling U.S. politics.