The growing importance of raw material supplies

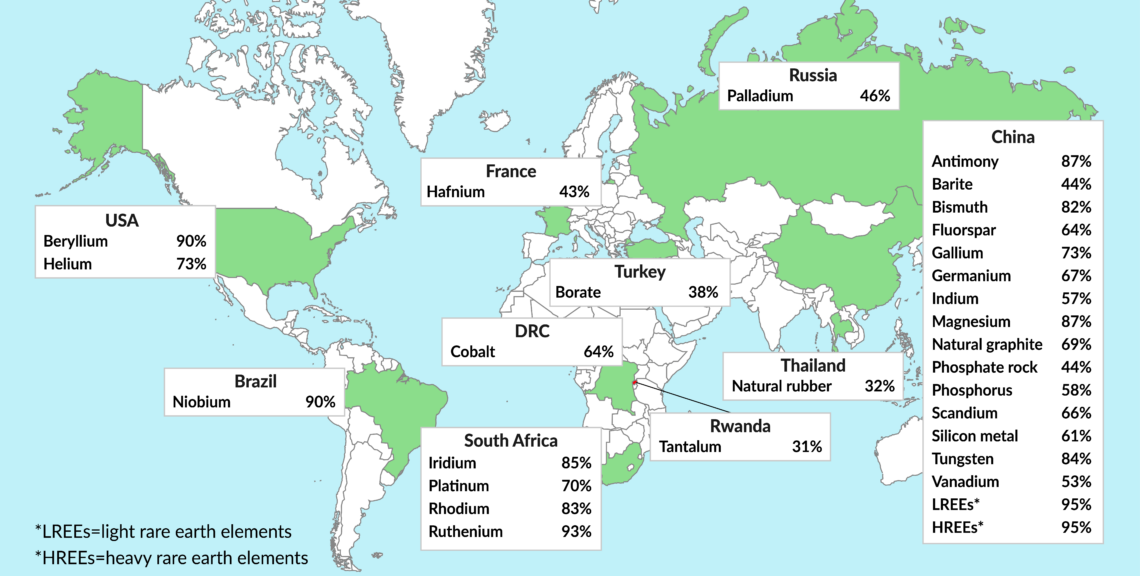

As new technologies grow in popularity, rare earths and other critical raw materials like lithium and cobalt are becoming crucial to the global economy. But their production is often concentrated in one or two countries, raising the risk that supply could be cut off suddenly.

In a nutshell

- Raw materials such as rare earth elements, cobalt and lithium are becoming increasingly important for the world economy

- China dominates the production and supply chains of most of these materials

- Beijing could use this advantage as a tool to pressure the West

Traditional analyses of energy security have almost exclusively focused on the potential for oil and gas supply disruptions from politically unstable or unreliable producer countries. However, digitization, the rise of renewables and other “green” technologies, the electrification of the energy sector, robotics and artificial intelligence could create a huge increase in global demand for critical raw materials (CRMs) – including rare earths, lithium and cobalt.

This shift will create new challenges, as the world turns to unfamiliar supply chains and sources. Currently, China has an unprecedented capability to harness this potential since it controls most of the world’s CRMs. Geopolitical risks to energy supplies will not fade with decarbonization and the end of the fossil fuel age.

The tsunami of new technologies being used in the energy sector and many other industries – such as lithium-ion batteries, robotics and artificial intelligence systems – will create new geopolitical risks since they are dependent on a stable supply of CRMs. In this regard, China matters not only as the world’s largest market for electric vehicles but also as the largest lithium-ion battery producer (59 percent of global production in 2018, predicted to rise to 73 percent by 2021). This arrangement could make carmakers in Europe, where there is little willingness to create lithium-ion cell production, dependent on China for years, if not decades.

Optimistic scenario: learning by experience

The security of supply for rare earth elements was already highlighted in 2010, when China, the world’s largest producer and exporter of these materials, suspended shipments to Japan in the midst of a diplomatic conflict over maritime territories and energy resources in the East China Sea. Beijing finally dropped its export quotas in 2015.

Under the optimistic scenario, as China’s CRM market would become more integrated into the global supply chain, Beijing would see that unilateral, national strategies and zero-sum thinking are counterproductive. China would then pursue a more cooperative, internationally minded approach.

Over the last decade, the EU’s share in global mining has steadily and substantially decreased.

The European Union is also learning by experience when it comes to securing CRM supplies. Obtaining access to CRMs and guaranteeing their affordability for its industrial and energy sectors have become significant concerns in Europe. While the EU is self-sufficient in construction minerals and a major producer of gypsum and natural stone, it is a net importer of most industrial minerals, despite being the world’s largest or second-largest producer of some of them.

Over the last decade, the EU’s share in global mining has steadily and substantially decreased. This has resulted in a loss of essential skills and expertise, not just in resource extraction, but throughout the value chain, including exploration, processing, recycling and substitution. It has also led to an underdeveloped role for the EU in ensuring access for European companies to CRMs worldwide, with shrinking opportunities for maintaining or expanding European technical and environmental standards.

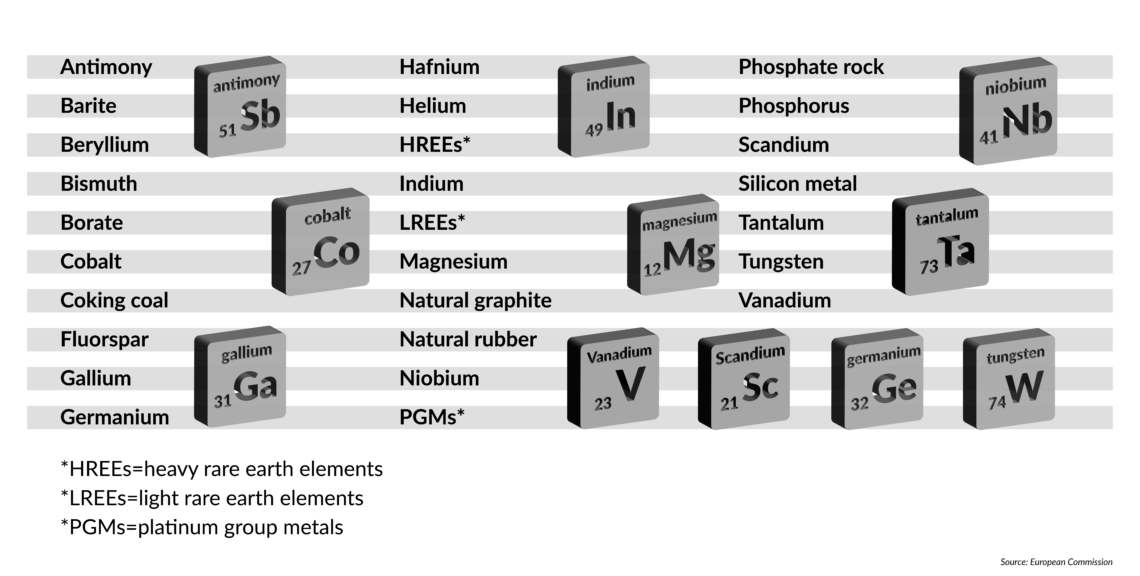

In 2010, the European Commission indicated 14 raw materials as “critical” for EU industries. In 2014, the figure climbed to 20, and in 2017, the list grew to 27.

Facts & figures

27 critical raw materials (CRMs) as identified by the European Commission

In 2010, the European Commission identified China as the most significant producer of CRMs. Since then, it has developed various strategies to cope with rising demand for these materials and the related supply security challenges, including reuse, reduced use, substitution and recycling of CRMs.

The overall supply challenge for CRMs is not so much geological scarcity, but the fact that their production is often limited to just a few countries and companies. They are only scarce because most of the deposits scattered around the world are unprofitable to extract.

As CRM demand rises on the back of the technological competition between China and the West, Latin American and African countries could come out big winners, due to their reserves of lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, iron ore, bauxite, chromium, silver and zinc. However, CRM producers and exporters are confronted with traditional “rentier state” challenges, like resource nationalism and the “resource curse,” as well as unprecedented international attention on their mining practices and conditions.

Facts & figures

The “resource curse” refers to the fact that countries with an abundance of natural resources often have lower economic growth, are less democratic, and are less developed than countries with fewer natural resources.

Under this optimistic scenario, the development of these resources would not only depend on attractive mining and extraction conditions, but also on political stability and social acceptance. That means the source countries would respect higher environmental standards, avoid human rights abuses, provide safe working conditions and prevent child labor, as well as promote affordable, clean energy. International certification schemes such as the “OECD Due Diligence Guidance” and conflict-free sourcing initiatives offer instruments for more transparency and international collaboration to increase environmental, social and labor standards in developing countries.

Western mining companies, fearing for their international reputation, are already increasing renewables in their energy mix and are trying to reduce the negative environmental impacts that come with CRM production. As the use of green technologies grows and the world becomes more dependent on CRMs, international attention will increasingly fall on these companies’ environmental standards and production methods. This will encourage more international cooperation and increase the adherence of Latin American and African countries to adopt international standards.

More realistic scenario: growing supply security challenges

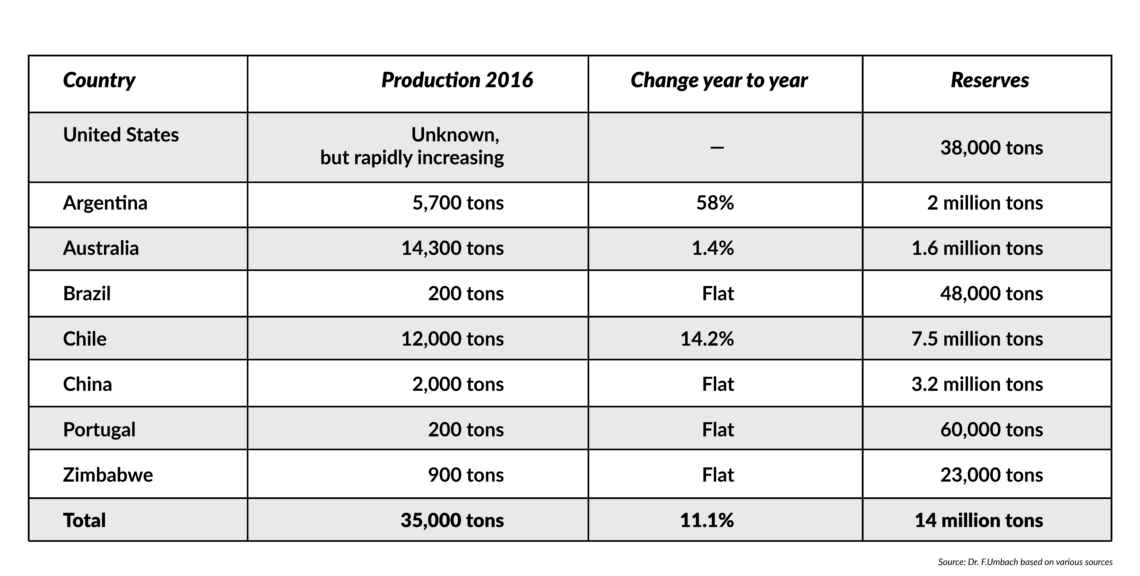

CRM production is geopolitically more problematic than that of conventional oil and gas – particularly when considering the likely increases in demand that will occur. At present, 50 percent of CRMs are located in fragile states or politically unstable regions. In 2017, a World Bank report warned that electricity systems are more “material-intensive” than current fossil-fuel supply systems. It projected that the worldwide demand for metals could double, and demand for lithium could increase by more than 1,000 percent in the coming years. Many lithium experts say not enough attention is being paid to the security of the metal’s supply, considering the global expansion in battery use.

Facts & figures

Worldwide lithium production

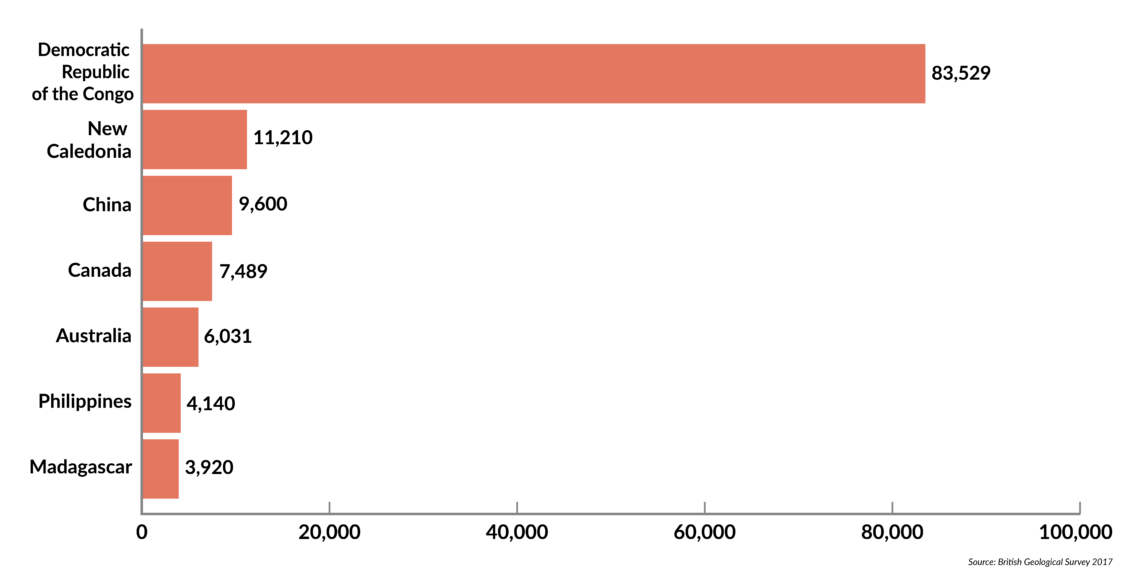

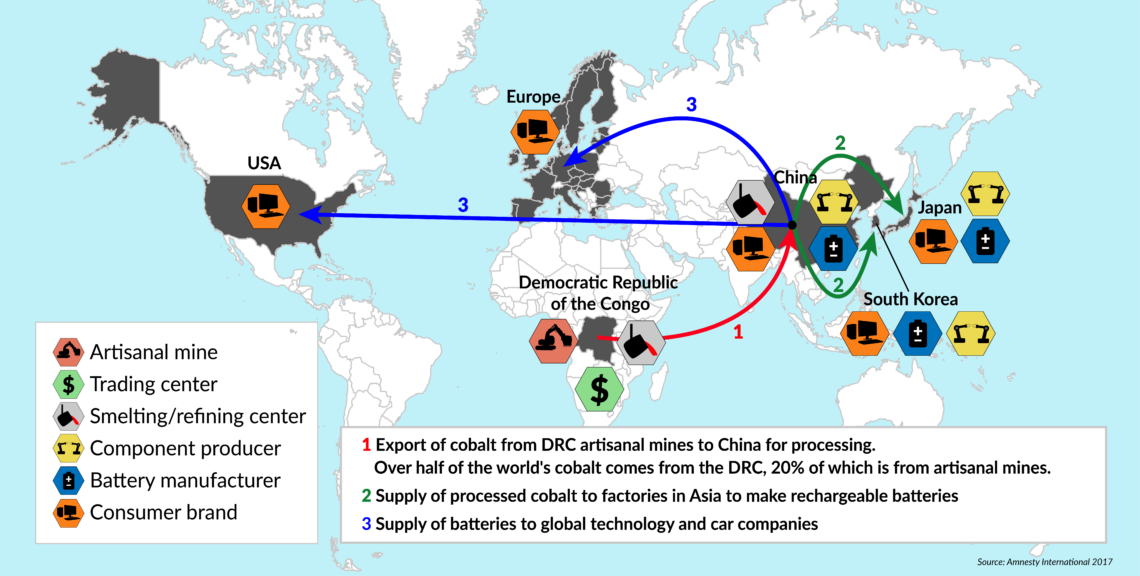

The global supply of cobalt will also remain tight in the short term. More than 50 percent of the world’s cobalt is produced in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) – a country that for decades has been plagued by violent conflict, instability, bad governance, human rights abuses, child labor and widespread corruption.

Forecasts suggest that the amount of cobalt used in lithium-ion batteries for electric vehicles alone will increase from 46,000 metric tons in 2016 to 76,000 tons by 2020 and could even reach 180,000 tons by 2026. For every additional million electric vehicles produced, an extra 8,000 tons of cobalt is currently needed. Total worldwide cobalt production could rise from 123,000 tons in 2016 to 314,000 tons by 2030.

China currently produces 80 percent of the world’s cobalt chemicals. Much of its feedstock for cobalt concentrates comes from the DRC.

Facts & figures

Major cobalt producing countries

The amount of cobalt (tons) that is mined, by country, 2015

In most cases, geology is not a factor in constraining CRM supply. However, geopolitical and local political conditions, as well as rapid market changes, can lead to supply shortages, price spikes and volatility, and growing dependency on such resources. Environmental risks, corruption, social factors (“not-in-my-backyard” attitudes, social acceptance, etc.) and political machinations can further constrain CRM supply. The biggest worries include:

•accidental supply disruptions or price hikes

•intentional supply disruptions, such as when exports or pricing are used as political instruments

•unequal market conditions, causing an uneven economic playing field

•governance issues, including protectionism and export restrictions

Facts & figures

Movement of cobalt from artisanal mines in the DRC to the global market

The dangers are not limited to primary natural resources and CRMs. They also include the security of deliveries of semi-manufactured goods, refined goods and finished products. Moreover, risks such as manipulated prices, supply restrictions and attempts at forming cartels do not only apply to producing and exporting countries. Powerful companies (both state-owned and private) have also implemented opaque pricing mechanisms. Global supply chains are becoming increasingly complex, boundaries between physical and financial markets are being blurred, and market platforms are weakly governed. With this, price manipulation by trading houses, major producers and financial institutions has increased. All this threatens the future CRM supply security.

Developing countries may face even more water shortages, rising emissions and toxic pollution.

While the environment might get cleaner in developed countries as a result of expanded battery use for electric vehicles and renewables, the opposite might be true in the developing countries producing CRMs for the rich world – their environmental and social costs are increasing with expanded mining. These countries may face even more water shortages, rising emissions and toxic pollution. They also have to find ways to curb human rights abuses and implement international labor standards.

Mining supply chains are rarely fully transparent, despite efforts to improve industry practices for responsible sourcing. Some of the largest mining companies still do not publish any emissions targets. Ultimately, achieving improvement in this area depends on the political will of the countries in which the mining firms operate.

A lot also rides on the raw material supplies and investing strategies of China, which will remain the biggest wild card for the CRM supply to the West. Metals prices have for years been determined by China’s industrial demand. As prices have recently recovered, the growing dependence on the development of China’s electric-vehicle and battery markets is compounded by an equally rising dependence on CRMs such as rare earth elements under Chinese control.

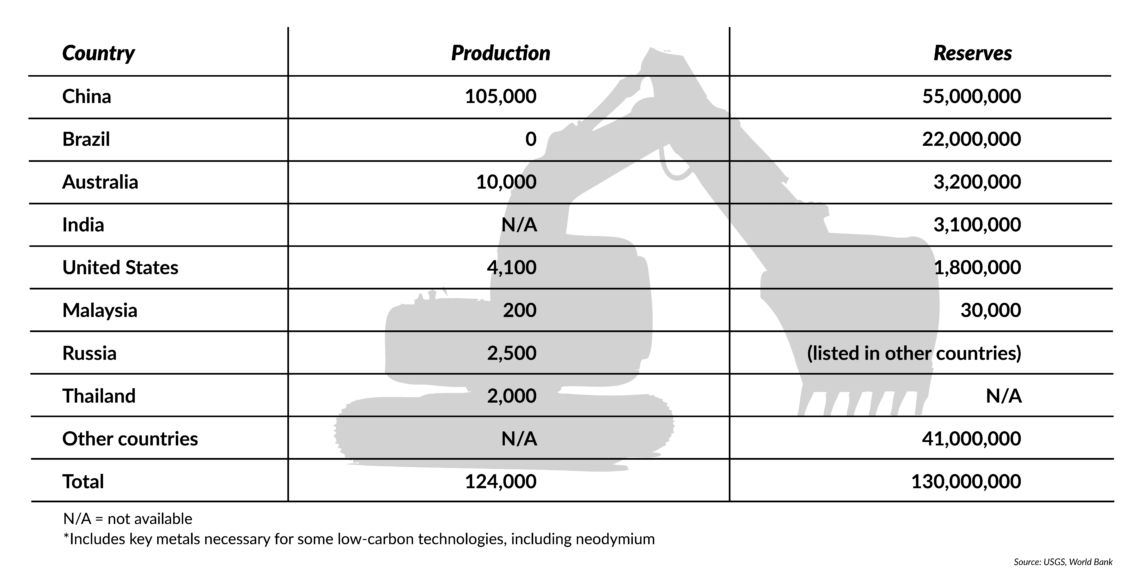

Facts & figures

Rare earth production and reserves in 2015 (in metric tones)

The trend toward resource nationalism in China and its overall focus on the most disruptive technologies for its technological arms race with the West raises doubts about how China might use its de facto production and export monopoly on rare earth elements. China is systematically increasing its strategic control over the global supply chains for lithium, cobalt and other CRMs. In 2017, China still accounted for around 85 percent of REE supply (105,000 metric tons in 2017) and over 66 percent of its global demand.

Given the overall rise in demand of CRMs, securing access to – and strategic control of – stable, large-scale, high-quality sources will become increasingly important. This could lead to greater geopolitical competition.