2019 Global Outlook: China’s regional impact

China will cast a long shadow in East Asia again this year. 2019, however, is shaping up to be less volatile than 2018. In security matters, expect China to use more “carrot” than “stick” as its neighbors balance Beijing against Washington.

In a nutshell

- Beijing will aim to use less coercion against its neighbors this year

- A stimulus program will probably be implemented to boost China’s economy

- China’s leadership is eager to end the trade dispute with Washington

- These factors should bring stability and increased investment to the region

2018 saw plenty of volatile moments for both security and economic development in East Asia. The summit between United States President Donald Trump and North Korean leader Kim Jong-un ostensibly eased the tension between their two countries, although much remains unresolved. President Trump’s propensity for making unilateral decisions has brought uncertainty to the international order, including in the region.

The trade war between China and the U.S. has cast a shadow over the global economy. While free trade has been under fire for several years, China is also practicing a kind of “multilateralism a la carte,” which is undercutting liberal economic norms. Some countries are trying to establish a new economic order. The completion of big bilateral and regional free trade agreements is a sign of the World Trade Organization’s diminished ability to advance a multilateral trade regime.

This year, China, the world’s second-largest economy, will again have a huge impact on global developments, especially when it comes to security, trade and investment in East Asia.

Diplomatic push

There are four main hot spots in East Asia: the South China Sea, North Korea, the Taiwan Strait and the East China Sea. China has been playing a key role in determining how the tensions in all these places play out.

Starting in 2018, China changed the way it deals with its neighbors and the U.S.

Since 2015, President Xi Jinping has constantly sought to leverage China’s growing economic, diplomatic and military clout to establish regional preeminence and expand its influence globally. Over the past few years, Beijing has become increasingly assertive. Starting in 2018, however, China changed the way it deals with its neighbors and the U.S.

In the South China Sea, China has adopted a carrot and stick approach toward its neighbors. While formally working with other countries in the region to draw up a “code of conduct” for the South China Sea, Beijing has sought more diverse, bilateral solutions to disputes. Joint oil exploration programs with the Philippines and Brunei, and a revival of a “communist brotherhood” with Vietnam, are all part of its tactical shift to “soft” (noncoercive) diplomacy. At the same time, President Xi has excluded the U.S. from the regional security discourse on the South China Sea, despite knowing that all the other claimant states welcome the U.S.’s intensifying activity there.

Beijing’s diplomatic push will certainly play a positive role in the security and economic development of the region. In the long run, however, an armed conflict with the U.S. will become unavoidable unless both sides can agree to allow freedom of navigation in these waters.

Shortly before the Trump-Kim summit in Singapore last year, China’s abrupt engagement with Kim Jong-un helped Beijing avoid being marginalized in Korean Peninsula politics. The strengthening of ties between Mr. Kim and President Xi have complicated the denuclearization process. China has demonstrated that it can easily sabotage the breakthrough achieved at the Trump-Kim meeting in June 2018. For Mr. Kim, however, it is a big advantage to be able to play Washington, Beijing and Seoul against each other. Will he make good use of the cards he has been dealt? 2019 will be decisive.

Balancing act

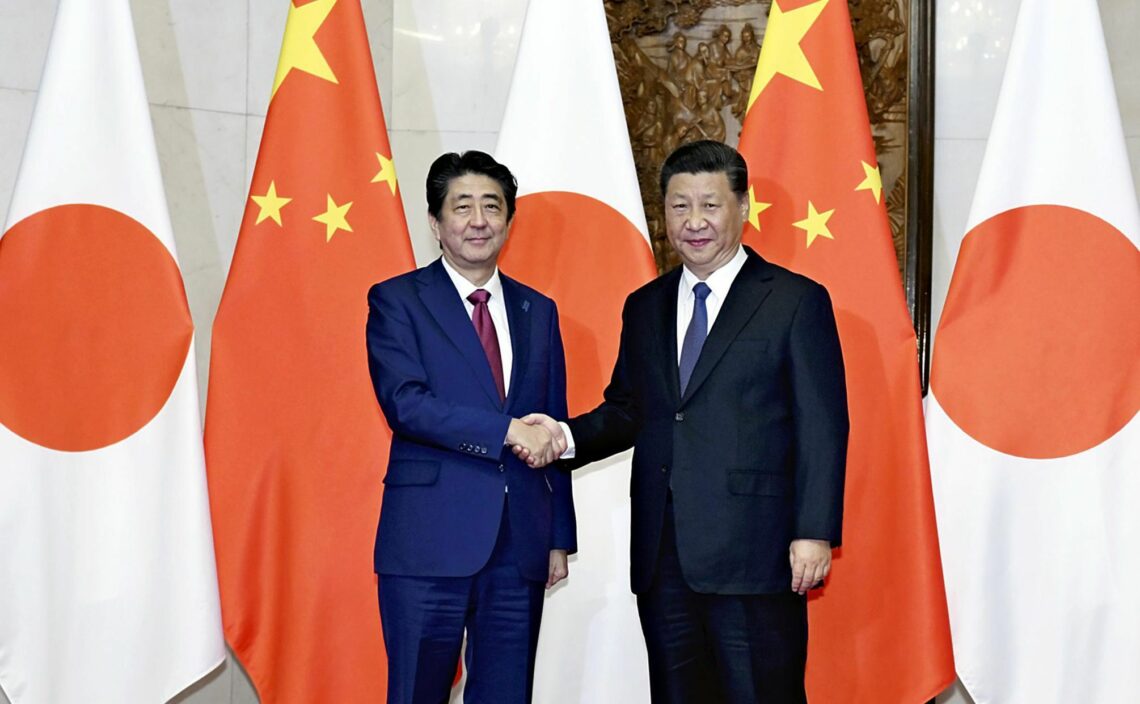

Beijing’s rapprochement with Japan has greatly eased tensions in the East China Sea. However, Tokyo knows that Beijing’s efforts are driven by its opportunist thinking: the Chinese leadership is looking for a way to curtail the impact of the trade war with Washington. While Shinzo Abe embraced the normalization of bilateral relations, last year Japan’s military activated its first marine amphibious unit since World War II. In March this year, it will establish its first cyber protection unit.

Taiwan under President Tsai Ing-wen had been increasingly squeezed by China on all fronts. Her party’s poor showing in local elections in November 2018, however, has prompted Beijing to take a “wait and see” approach. Although President Xi recently emphasized that China will make “no promise to renounce the use of force” to achieve reunification, his biggest headache is the economy, not Taiwan. Moreover, the Asia Reassurance Initiative Act (ARIA), which President Trump signed at the end of 2018, reinforces the support Taipei can expect to get from the U.S.

This year, most governments in the region will try to balance the influence of China and the U.S., rather than choosing confrontation with either. Some Asian states prefer a “hard” balance by enhancing their military capabilities, as Japan and Taiwan have done. Most members of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), however, are more inclined toward “soft” (economic and diplomatic) balancing.

For its part, North Korea has its own way of balancing the two global powers. The sum of these various balancing strategies should favor economic growth in the region in 2019.

Economic slowdown

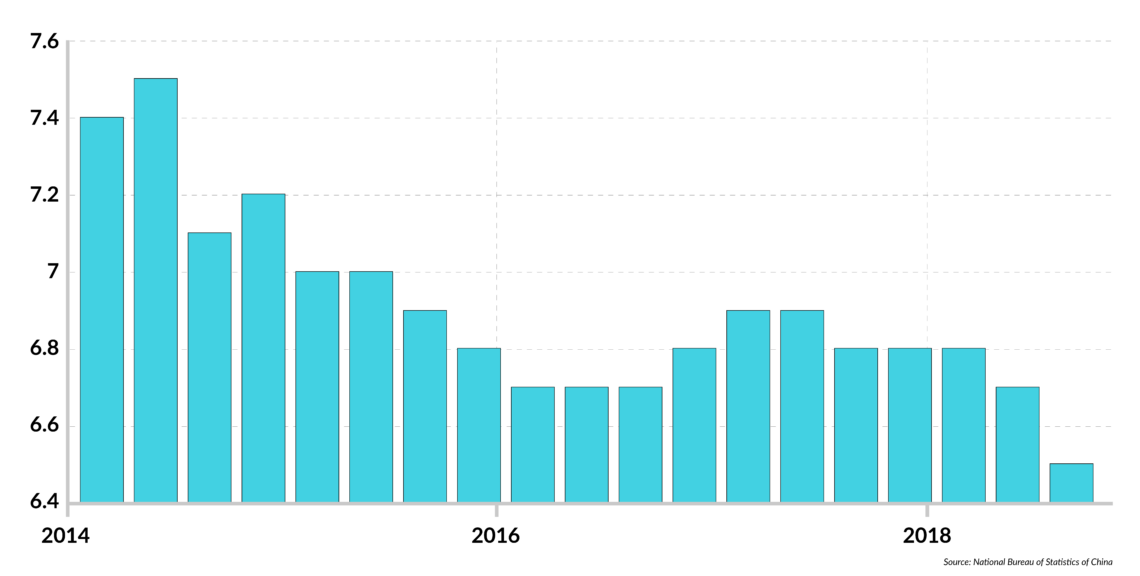

While China’s economic growth has slowed recently, the country remains an engine of the global economy. The shine, however, is wearing off. Official Chinese government statistics say gross domestic product (GDP) grew by 6.5 percent in 2018. However, one institution that has not been named but which was cited by Renmin University School of Finance Professor Xiang Songzuo, calculated that China’s economic growth last year may have been as low as 1.67 percent. Regardless of which data are more accurate, it is clear that China’s economy has decelerated remarkably. Economic indicators for November and December 2018 painted a gloomy picture of exports, industrial production, consumer spending and foreign investment.

Facts & figures

Slowing engine

China's GDP growth rate (%), 2014-2018

The faltering pace of political and economic reform has already hit the country’s private sector hard. Trade tensions between the U.S. and China have accelerated private businesses’ decline. More than 5 million private companies – a sixth of the total – closed in 2018. Together, the country’s more than 3,000 publicly listed enterprises generated very little profit last year. Some 80 percent of their earnings came from banks and real estate firms, while 1,774 small and medium-sized listed companies posted profits not much larger than those of a single lender: the Industrial and Commercial Bank of China (ICBC).

Auto and property sales are slowing, while demand for consumer goods expanded by 8.1 percent in November, from 10.2 percent a year later. These indicators will likely continue to weaken.

For these and other reasons, Beijing is eager to end the trade war with Washington, and the Chinese authorities have already taken several measures to boost imports from the U.S. In December, a draft law was introduced to ban forced technology transfer, one of the Trump administration’s biggest complaints against the Chinese.

There are two potential outcomes of the ongoing bilateral trade negotiations. In the most likely scenario, some sort of consensus will be reached by the end of February. However, the Trump administration will have to settle for China making only cosmetic changes to its trade practices. Its economic structure will remain broadly untouched.

A second, more pessimistic scenario cannot be ruled out: President Trump may be pressured by the U.S. Congress to take a tough stance toward China’s halfhearted efforts at structural economic reform. He would then follow through on threats to increase tariffs on more than $200 billion worth of Chinese imports in March.

As the trust gap widens, the market in the West for companies like Huawei will shrink.

Whatever happens, the distrust between the West and China will endure. Beijing’s advances in telecommunication technologies, for example, were accompanied with increased suspicion from the U.S. and other Western countries. As the trust gap widens, the market in the West for companies like Huawei will shrink. At the same time, however, Chinese companies will increase their share of the digital sector in other parts of the world.

Additionally, China’s difficult economic environment will force it to scale down projects related to the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), diminishing its economic influence. So far, some 270 BRI projects have been put on hold or canceled, accounting for about 32 percent of the total projects’ value.

The Chinese government recently approved measures to boost domestic demand and open new markets to offset the negative impact of the trade dispute. Tax cuts, job creation and helping the private sector will be a priority. With proactive monetary and fiscal policies in place, the country’s economic deceleration may ease by the second half of the year.

ASEAN’s gain

The security and trade tussle between the two great powers will favor ASEAN economies, especially Vietnam, Indonesia, Thailand and Cambodia. These countries have a total labor force of 350.5 million and 60 percent of their total population is below the age of 30. This offers great potential to partly replace the supply chain economies in China’s Yangtze and Pearl River Deltas.

ASEAN will be a natural magnet for companies looking to diversify away from China this year.

Moreover, Vietnam will greatly benefit as one of the initial signatories to the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the successor to the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) agreement that was scrapped after the U.S. backed out. ASEAN will be a natural magnet for companies looking to diversify away from China this year.

Nevertheless, there are plenty of uncertainties. Between February and May, India, Indonesia and Thailand will hold elections. Their outcomes will have a significant impact on the region.

Amid moderating international trade and tightening global financing conditions, growth in emerging markets and developing economies is projected to reach 4.7 percent in 2019, up from 4.5 percent in 2018. China’s growth is expected to slow to between 6.2 and 6.0 percent.

Scenarios

East Asia looks to be less volatile in 2019 than in 2018. The Chinese leadership will focus on its economic problems by applying a moderate stimulus policy, relegating the economic hawks to a back seat. Western companies operating in China must be prepared for the purchasing power of local consumers to shrink this year. However, ASEAN countries can pick up much of the slack from China. Whether East Asia remains geopolitically stable and economically robust after 2019, however, will depend on the interaction of the two superpowers.