China: what’s next? Unemployment

The rising labor costs and low productivity growth in China may lead to a decline in consumer confidence and poor performance of the economy.

In a nutshell

- Rising labor costs are more of a threat to the Chinese economy than the U.S. trade-rules challenge

- Rising wages mean China is losing its competitive edge

- Under such conditions, a spark could cripple citizens’ confidence and ignite an economic showdown

China’s troubles are multiplying. Although consumer spending and the real estate market are still growing fast, recent data show that industrial output rose relatively slowly during the past 12 months. This August, industrial output was only 4.4 percent higher than a year earlier.

Moreover, Chinese authorities have sent mixed signals. On the one hand, they have declared that this year the country’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth will remain above the 6 percent threshold (during the past 30 years Chinese growth averaged 9.5 percent and was 6.6 percent in 2018). On the other, they have announced that the final figure could be below 6 percent, and they have encouraged banks and companies to lend or borrow more by putting at their disposal a new wave of expansionary credit policy. What should we make of these contradicting statements? What can be expected for the future?

Scarce labor

We have always maintained that the drop in Chinese growth is going to be gradual and that relatively slow growth will not end with a crash. This still holds true. Yet, recent developments suggest that problems are piling up and that, for the time being, Beijing’s economic decisions have not paid off from a global perspective. New solutions are needed.

In contrast with what countless observers claim, China’s most pressing problem is not the trade confrontation with the United States. It is future confidence at home, which feeds domestic consumption, and which in turn is the primary driver of entrepreneurial decisions (and good investments). In the broad scheme of things, the trade dispute with the Trump administration matters, of course, but only indirectly. Other questions are far more critical: rising labor costs, relatively low productivity growth and competition from other developing countries. These three elements play a crucial role in shaping domestic trust. The future of the Chinese economy depends on how the authorities will answer these challenges.

Qualified labor is scarce and segments of the labor market are under pressure.

Labor costs have been rising rapidly. China’s vast rural population was expected to provide a nearly unlimited labor supply to manufacturing and service companies, and massive efforts were invested in providing technical education to the young. Yet qualified labor is scarce and significant segments of the labor market are under pressure. As a result, during the past 10 years, nominal wages have risen by a factor of 2.7, while consumer prices and the exchange rate have remained more or less stable. If this trend continues, China will no longer be competitive in several industries. Beijing might be tempted to resort to protectionism to help domestic producers and maintain confidence in the economy. If it eventually decides to do so – although it is unlikely – President Trump will be a convenient scapegoat.

Productivity growth is also problematic. The issue is not productivity growth per se since the Chinese figure is still far better than that of most countries (officially, productivity grows at about 6.5 percent a year). The crux of the matter is the size of investment. In China, the investment-to-GDP ratio is currently nearing a staggering 45 percent. During the past 50 years, the average figure for the U.S. was 22.2 percent, which is also the approximate figure for Germany. Although investments are generally welcome everywhere, this could be bad news for China.

Firstly, such a high rate of fixed capital formation means that considerable resources are taken away from consumption and allocated to expanding production. Consumers might tolerate forced savings and low purchasing power if returns are high but will feel uncomfortable otherwise. We do not know how high the “high returns” should be in these circumstances. One fears the tipping point is near.

Facts & figures

Annual growth rate of China's gross domestic product

Secondly, the data on labor productivity consider the value of production and the number of workers. However, taking into account that production includes more and more oversized infrastructure, empty buildings, underutilized factories and rapidly increasing inventories, it is apparent that the data on Chinese productivity is, in fact, misleading.

Indeed, one could presume that the actual growth and productivity generated by the technological improvements incorporated in the new capital stock are modest: investment-led growth and prestigious projects could be a statistical veil that hides a fragile reality. In other words, high investment no longer predicts future growth. It rather expands production capacity and boosts the statistics. On the other hand, it contributes to absorbing the workers that might otherwise remain unemployed and become a source of tension. However, these vast efforts in building up the stock of capital hide the fact that technological growth is disappointing. The gap between China and other developing countries is closing. The narrowing of this gap (and rising labor costs) makes investors wonder about the returns on their investments in China, regardless of what Mr. Trump does.

Expansionary policies

The upshot of our argument, therefore, is that expansionary fiscal and credit policies will not do. An indiscriminate rise in public expenditure that targets the construction industry and infrastructure might contribute to keeping the unemployment rate low (it is currently 5.3 percent, according to official statistics), but will do little to raise productivity, restore confidence and encourage private investment in long-term, relatively risky projects. Easy credit for local government authorities and companies at large might be counterproductive, for it encourages investments in low-return and possibly wasteful projects.

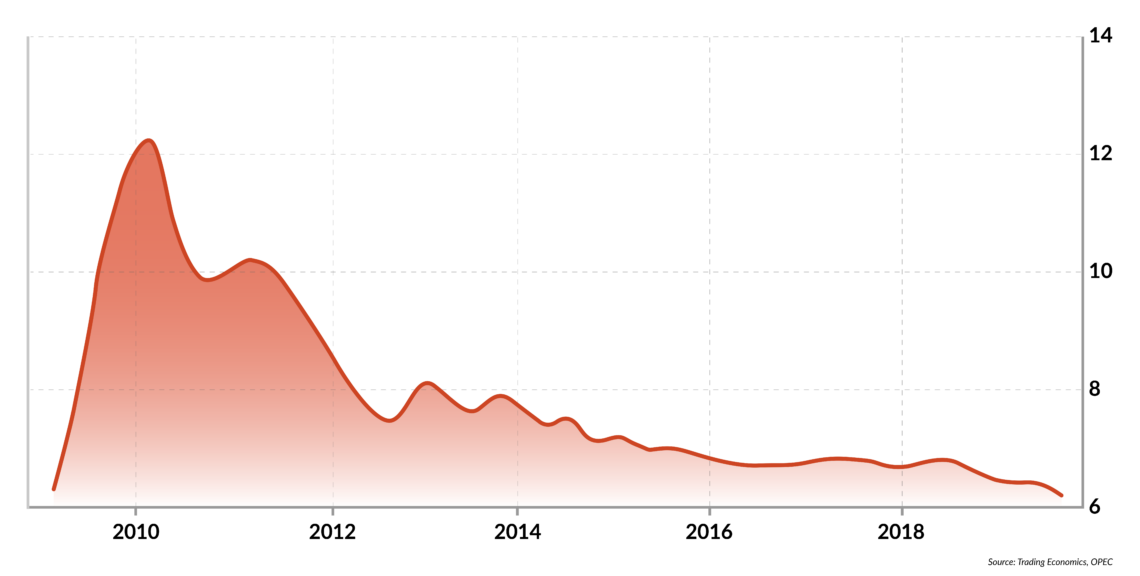

These effects are not mere theorizing, as the weak pace of the EU economic development since 2008 shows and Chinese lawmakers have undoubtedly noticed. We suggest that the first variables to monitor are the nominal wage rates and unemployment, with emphasis on youth unemployment. The latter might trigger disillusion at home, with dire economic and political consequences.

Investors wonder about the returns on their investments in China, regardless of what Mr. Trump does.

In this light, lax fiscal and monetary policies can be helpful, at least for a while. Providing ammunition for public expenditure and liquidity to ailing firms keeps (bad) business alive. These measures prevent massive and generalized layoffs and make it easier for the young to find employers. Of course, nominal wages are also likely to rise, which keeps people happy and confident about the future. However, this works as long as inflation remains low – when the rise in nominal wages is also a rise in real terms – and as long as public debt does not cause concern.

Somewhat surprisingly, both requirements are now being met, even though expansionary policies have been underway for several years: inflation in China is currently stable at about 2.7 percent, according to the official statistics, and at the end of 2018, the debt-to-GDP ratio was a relatively modest 36.2 percent.

Scenarios

Will these policies succeed in making the Chinese confident about their future? Not quite. Expansionary policymaking will fail to solve the fundamental stumbling blocks of the Chinese economy: low technological growth, fast-rising labor costs and – more importantly – massive hidden unemployment. The main question remains whether and how the Chinese will address the rising tensions and adjust to relatively low growth and strain in the labor market. The days of reckoning could materialize in the years ahead.

The extent to which the Chinese population believes in the future of its economy is crucial in this context. China can undoubtedly deal with lower exports to the U.S., and Chinese pride is strong enough to make the economic consequences of a trade confrontation sustainable. To hurt Chinese leadership, President Trump should go for unilateral trade liberalization, thus forcing Beijing to look for other (hard to find) excuses justifying the forthcoming difficulties in the labor market, regardless of the current official statistics. In mainland China, pressure for jobs and income redistribution could soon prove much more potent than demands for political liberties.

Much remains to be done. So far, the Chinese strategic choices of the past have hardly produced the expected results. Efforts to buy assets in the rest of the world and secure a captive trading area through massive infrastructural investments – the Belt and Road Initiative – have involved a commitment to spend significant sums, but the returns remain questionable for a variety of reasons. These include difficulties in adapting to foreign cultures and management styles.

The only realistic way out is to make further significant steps toward deregulation and privatization. Rampant unemployment and rising unrest lurk around the corner. The Chinese have bought time by resorting to money printing and government expenditure. However, time is running out and any trigger (including the current trade dispute or unrest in Hong Kong) could result in a crisis.

The actual risk here is not a soft landing. This can be managed, as has happened before. The real danger is a spark that would cripple confidence and ignite an economic showdown, with much broader collateral damage.