China’s military puts Indo-Pacific on edge

Beijing’s claims to Taiwan and most of the South China Sea are increasingly backed up by a stronger and more capable military, particularly its naval forces.

© Getty Images

In a nutshell

- As China builds a navy that rivals America, tensions are heightened in the Pacific

- The U.S. has responded by strengthening security relations with regional allies

- More displays of Chinese military can be expected, especially around Taiwan

The People’s Republic of China is the greatest security challenge in Southeast Asia and the Pacific. For at least a decade, Beijing has made significant investments in its military and security, particularly naval, forces while expanding the boundaries of its desired area of control around its mainland. These efforts have included not only an increased military and paramilitary presence in the South and East China seas but new militarized areas and security arrangements across the Indo-Pacific.

Beijing’s moves have created anxiety for its neighbors, many of whom are security partners of the United States. The U.S. and other Indo-Pacific countries have responded by taking a renewed interest in the region and reaffirming the international norms that have helped it to prosper. For example, the U.S. and its partners are taking new steps to deepen their own security agreements over Beijing’s objections. Meanwhile, China’s increasing military presence increases the likelihood of regional conflicts or accidents.

See also

Can the U.S. and Taiwan avoid a war with China?

China’s changing security interests

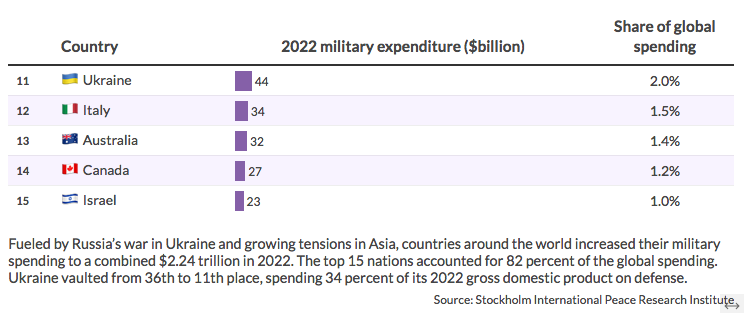

After the U.S., China spends more than any other country on its military. In 2022, the U.S. spent $877 billion, or 39 percent of global defense spending, compared to China’s $292 billion, or 13 percent, according to Stockholm International Peace Research Institute.

But the rate by which China is investing in its military is considered by some as the largest military buildup since the end of World War II. In the seven years between 2015 and 2021, Beijing spent as much on its military as it did during the 21 years before 2015. Beijing also has an equivalent domestic security budget that funds such armed forces as the Coast Guard. But unlike the U.S., which has security investments worldwide, Beijing’s interests are primarily in the Indo-Pacific.

Since 2009, Beijing has been pushing the boundaries of its desired control away from its mainland. That has included efforts to claim most of the South China Sea as its own, an assertion dismissed by Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Taiwan and Vietnam. Confrontations have occurred in the disputed waters, such as on April 23, when two ships from the China Coast Guard almost struck one from the Philippines Coast Guard.

President Xi Jinping’s rise to power in 2013 has fueled Beijing’s more assertive diplomatic efforts and military posture. China’s forces are becoming more of a tool of the Chinese Communist Party’s political interests, which now dictate increased naval presence and militarization of several islands in the South China Sea.

Beijing has also made greater use of security forces, such as its Coast Guard and maritime militia, for surveillance and harassment. Since the Coast Guard and civilian-operated maritime vessels are not generally considered part of the military, their use has allowed Beijing to assert its interests without generating a reciprocal military response by American or other forces in the region.

No other country has a significant counterpart to China’s Coast Guard, which cooperates with China’s Navy. The number of Coast Guard and maritime militia vessels in China has tripled in the last 10 years, making their size nearly equal to China’s Navy.

But the way Chinese forces behave differs depending on the region. Chinese forces are seen as more aggressive in the South China Sea than it is in the East China Sea. There are multiple reasons for this difference, including Beijing’s greater interest in the resources of the South China Sea. But China’s military activities have increased in scale and frequency in multiple areas. It has become routine behavior for the Chinese Coast Guard and maritime militia to block Philippine vessels, harass U.S. forces or conduct large-scale military exercises around Taiwan.

Facts & figures

Recent developments

Significant changes have occurred in Chinese and Western engagement in the Indo-Pacific in the last year. In February 2022, the Biden Administration published its Indo-Pacific Strategy. It has emphasized strengthening America’s relations with its regional partners, including expanding America’s diplomatic presence in Southeast Asia and the Pacific.

Shortly after, China and the Solomon Islands signed a new security agreement. While the agreement created unease, especially in the Pacific region, it hardly came as much of a shock given that the government in the Solomon Islands seemed to be drifting toward more engagement with Beijing since taking power in 2019.

Beijing’s interests are much more expansive in the Indo-Pacific. It was reported in June that China may also be building a military base in Cambodia, one of China’s few military partners. China is also looking for ways to bolster its existing security partnerships, including with Russia. The Chinese and Russian navies held a joint exercise in December, even as Russia kept up its war in Ukraine.

In response, the U.S. has also been deepening its security partnerships, especially those that were arguably neglected in recent years. The most impressive developments have been with the government that came to power in the Philippines in June. President Ferdinand Marcos Jr., the late dictator’s son, has reverted to a more pro-American stance than pursued by his predecessor Rodrigo Duterte. Under President Marcos, the U.S. and Philippines have had a series of high-level visits, new capacity training and joint projects with other regional partners such as Japan. The Philippines recently announced it would allow four new sites to be used by Philippine and American forces. There have also been ministerial-level meetings to modernize the bilateral security relationship. And during President Marcos’ recent trip to the White House, President Biden reaffirmed America’s ironclad alliance commitments to the Philippines.

The U.S. and its larger Indo-Pacific partners are also looking at ways to engage more in the region with small countries. Last May, the Quad partners (U.S., Japan, Australia and India) announced a new Indo-Pacific Partnership for Maritime Domain Awareness. This effort is meant to work with regional partners, including those in Southeast Asia, to help increase awareness of the types of activities in their nearby waters. And the U.S., United Kingdom and Australia continue to work toward security research and delivering nuclear-powered submarines to Australia.

Over the last several years, as China has been increasing its military presence, there have been concerns that the U.S. was less committed to the region. But these new engagements are meant to show otherwise. On top of new dialogue, there have been regular American freedom-of-navigation operations in the South China Sea, training exercises with Australia, Japan and the Philippines and frequent transit through the Taiwan Strait, including once with Canadian partners.

There is a difference between the American and Chinese military presence in the region. U.S. engagement has been consistent since World War II. Regular operations generally are small in scale and within international norms. The same cannot be said for Beijing, which notably increases its military and paramilitary presence. China’s military drills tend to happen in areas that see a lot of maritime traffic, increasing their destabilizing nature. As the activities of China’s navy, coast guard and maritime militia increase, they become more brazen, and close encounters with American and other forces could trigger accidents and altercations.

Facts & figures

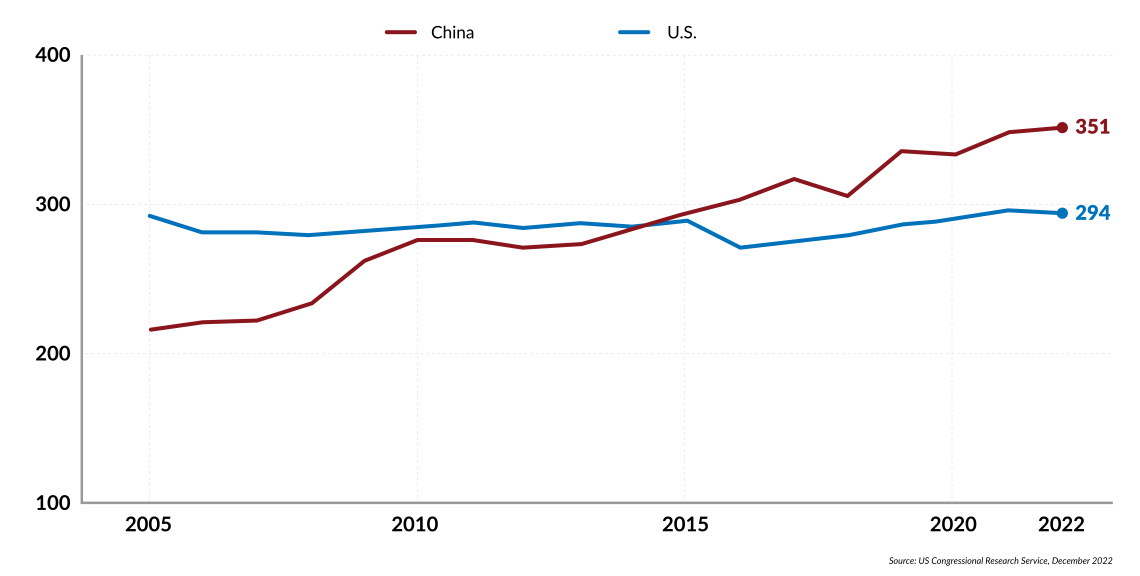

China has the world’s largest navy

Scenarios

Countries in the region are worried about China’s growing military presence. No matter the level of security cooperation with the U.S., there is still a general sense that America is on the other side of the Pacific and has less interest. The Biden administration has been working to show that the U.S. is committed to the region. Some countries are worried about being dragged into a conflict between the U.S. and China.

Beijing shows no sign of decreasing its military spending. It is also increasingly invested in its paramilitary forces, including its Coast Guard and maritime militia. This likely means more regular patrols or exercises throughout the region. Forces will also be deployed to express Beijing’s displeasure, such as when its objects to high-level meetings between American and Taiwanese officials. China’s military development in the region will continue to increase regardless of whether America and other regional actors step up their cooperation or not.

The rising military spending by China does not necessarily mean that conflict is imminent. The big fear is that China may be preparing to attack Taiwan in the next few years as part of its long-standing aim to reunify the island with the mainland. China’s military is expected to be more aggressive around Taiwan ahead of Taipei’s presidential election in 2024. The year 2027 marks the 100th anniversary of the founding of the People’s Liberation Army. It is also when the next Chinese Communist Party Congress will take place, and President Xi will seek an unprecedented fourth term.

Meanwhile, China’s aggressive behavior in the East China and South China seas is bringing America and its partners closer together. A higher level of engagement can be expected between the U.S. and allies and partners such as Japan, Australia, South Korea, India, the Philippines and Thailand. There will also be new engagements with nations such as Vietnam, Indonesia and Singapore. While the likelihood of conflict is low, China’s aggressive behavior has increased tension and raised the potential for accidents.