China’s profile is rising in Latin America

As China has been becoming an increasingly important player in the economy of Latin America, Beijing kept a low profile. Now, it can no longer avoid the spotlight. In Chile, Venezuela, Ecuador, Brazil, and Cuba, its position leads to challenges. The question is how assertive it become in imposing its will on the countries and how they react.

In a nutshell

- China is a major customer of Latin American commodities

- To shore up its position, it has made big investments in the region

- These investments have gotten it tangled in the region’s politics

- China may become more aggressive in trying to bend these countries to its will

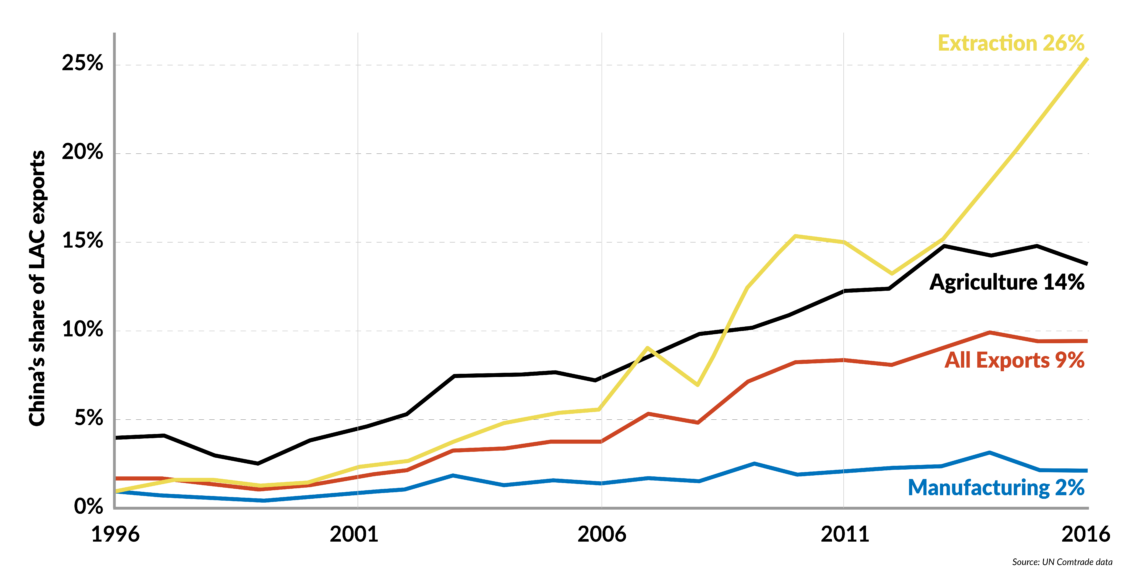

Over the past two decades, China has become a significant player in Latin America. The process began slowly, but as the Chinese economy began to hit spectacular levels of growth in the 1990s, it drove the price of several raw materials to historic highs. China became the leading buyer of many commodities produced in the region. That immediately made China an influential player in Chile (copper), Argentina and Brazil (soybeans), Peru (mining), as well as Ecuador and Venezuela (petroleum).

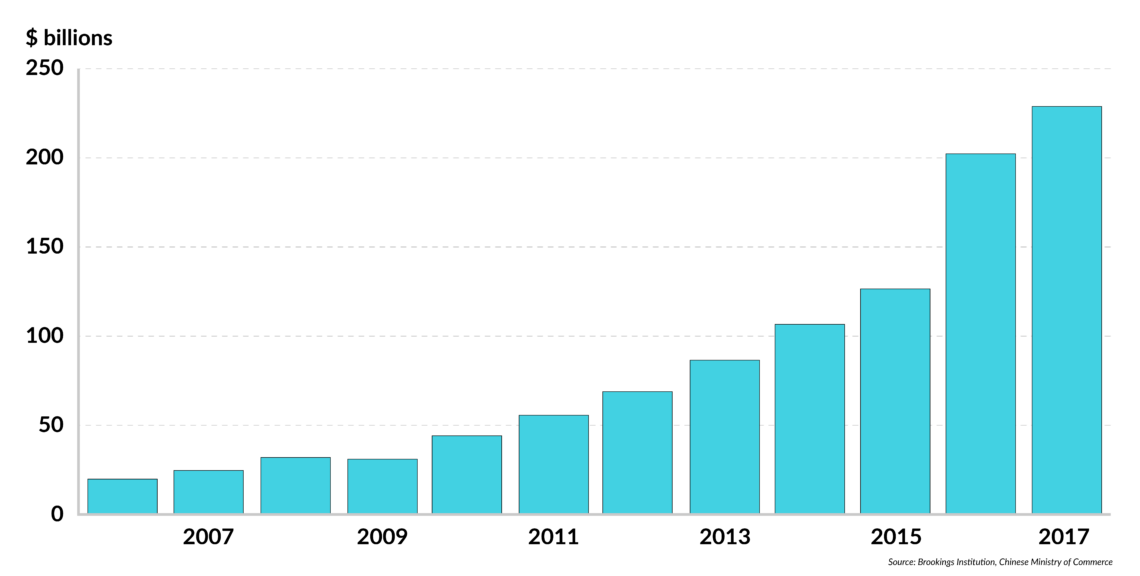

To buttress that role, China began to invest in a wide variety of industries throughout the region and to accumulate sovereign debt, especially in Venezuela and Ecuador. From 2005 to 2015, China’s influence expanded dramatically, but Beijing kept a very low profile. Recently, that has begun to change, and the Chinese government will have to come to terms with its new geopolitical role in the region.

It is no longer possible to consider China below the radar in Latin America, especially as the administration of United States President Donald Trump has expressed little interest in maintaining any semblance of a geopolitical posture there. Many countries in the region want China to play a larger role in their development plans. Given the heavy historical legacy of opposition to U.S. hegemony, they see Beijing as a welcome counterpoise to Washington, a role the Chinese government has taken some pains to avoid. And, while the Chinese pay little attention to governance in the region, they are gaining an unwanted reputation for their disregard for environmental concerns, especially around the Amazon basin, and for their low regard for local labor rights.

It is no longer possible to consider China below the radar in Latin America.

China’s involvement in the region takes various forms. How each of these evolves will determine China’s posture in Latin America. The Chinese role has become so important that there are now two academic centers devoted to following its every move in the region. One, the Global Development Policy Center at Boston University, has put together a rich database of macroeconomic activities, such as loans and investments. The other, the Centro de Estudios China-Mexico (CECHIMEX) at the National Autonomous University of Mexico (UNAM), does careful study at the firm level of Chinese investments in Latin America, and has a library of working papers on a variety of relevant topics.

Chile

China’s involvement in Chile began as a pure commodity play. Almost unintentionally on both sides, China has become the primary market for Chile’s principal export, copper. With the price of copper above $3.50/lb for most of the decade from 2004 to 2014, no one in Santiago complained about dependence on the Chinese market. When the price collapsed and the Chinese economy slowed at the same time, the Chilean government began to look for alternative trade options. The result was the Pacific Alliance, which has been a great boon to Chile, but by no means a complete solution to its dependence on copper exports. From China’s perspective, Chile is its most stable and reliable source of copper.

Now, however, the bilateral relationship is becoming complicated. A Chinese firm, Tianqi Lithium, is attempting to buy a controlling interest in Sociedad Quimica y Minera de Chile S.A. (SQM), the largest lithium producer outside of China. For decades, China has dominated the international lithium market and used that position to its geopolitical advantage. Chile is mindful of that history and its economic development agency, CORFO, has moved to block the sale of a 24 percent stake held by Canadian company Nutrien to Tianqi.

Beijing has made it clear that obstructing the SQM takeover will not be seen favorably.

Beijing has made it clear that obstructing the attempt to take over SQM, even though it is being made by a “private” Chinese company, will not be seen favorably. In such a squeeze, there is no one who can come to Chile’s defense.

It is interesting to note that SQM is in a joint venture with a company from Argentina to produce lithium from the Argentine side of the same salt flats under which the Chilean supply is found. At the same time, SQM is also a partner in a large development in Australia which is expected to come online by 2021. Tesla, Toyota, and Great Wall Motors Company have indicated their interest in joint ventures with SQM in the Chilean salt flats. Lithium is becoming one of the great geopolitical commodities of the 21st century.

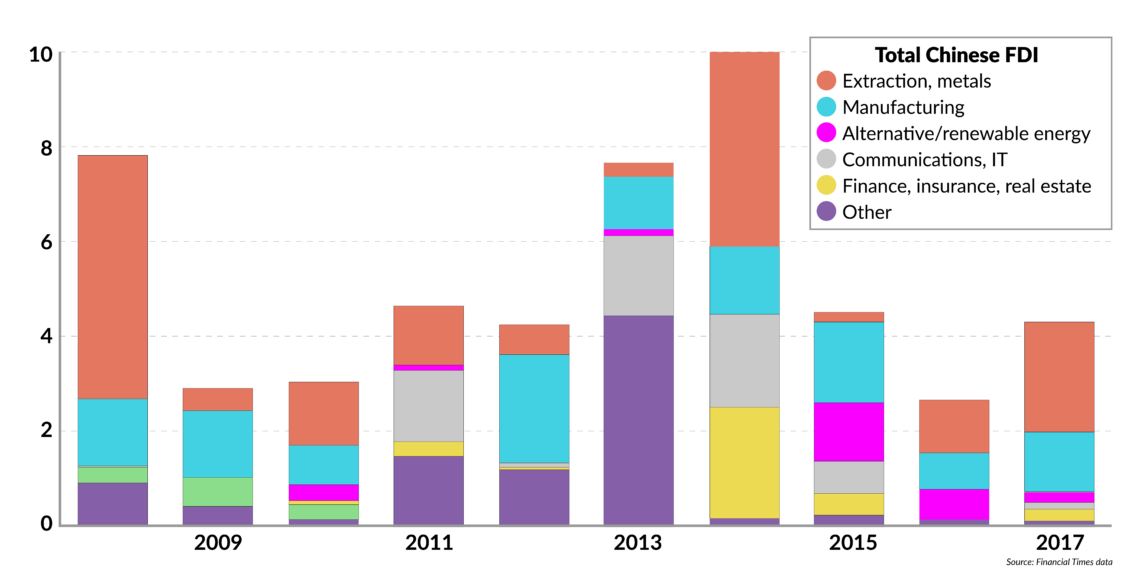

The pattern of Chinese investment throughout the region follows its initial geopolitical drive to feed its voracious appetite for commodities, although the results have varied over time and place.

Facts & figures

Chinese foreign direct investment in Latin America and the Caribbean by sector

2008-2017 (USD billions)

Venezuela

China’s involvement in Venezuela also began as a commodity play, but it has taken a much different turn than in Chile. As the price of oil started to rise at the turn of the century, China, utterly dependent on foreign sources of energy (except for its own dirty coal), began to enter a series of barter deals with the regime of former Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez, partly as a response to Chavez’s anti-imperialist policies. It was part of Chavez’s plan to create an anti-U.S. front in the hemisphere, which he called the Bolivarian Alliance for the Peoples of Our America (ALBA). As the price of oil soared to over $100 per barrel, China’s sense of urgency pushed it to buy more and more Venezuelan sovereign debt in exchange for oil at fixed, moderate prices.

Venezuela’s national oil company, PDVSA, cannot produce as much as it did 30 years ago.

Then, the price of oil collapsed. Worse, with the Venezuelan government in the hands of Nicolas Maduro, who succeeded Chavez after he died in 2013, the country’s oil production went into free fall. The national oil company, PDVSA, cannot produce as much as it did 30 years ago. Its rig count has declined each month for the past year, suggesting that it will not be a simple issue to restore production, no matter what the oil price may be over the next few years.

As a consequence of the economic disaster, Venezuela has essentially gone into default on its sovereign debt and the debt of its national petroleum company. Chinese banks and government-supported creditors hold nearly $60 billion of that debt, the majority of it backed by commitments of Venezuelan oil. But production continues to fall, the government teeters on the edge of insolvency and the country’s humanitarian crisis grows more alarming by the day. The Chinese are faced with the problem of what to do with their portfolio of debt, while the supply of oil that is supposed to pay for that debt becomes more questionable with each passing day. Venezuela has asked China to restructure the debt, but the Chinese have refused to negotiate.

Ecuador

Ecuador represents a case that might be considered a hybrid between the pure commodity play in Chile and the geopolitical commitment in Venezuela. Under President Rafael Correa, a fierce anti-imperialist, Ecuador was a founding member of ALBA and entered into a series of debt-for-petroleum swaps similar to the pattern followed in Venezuela.

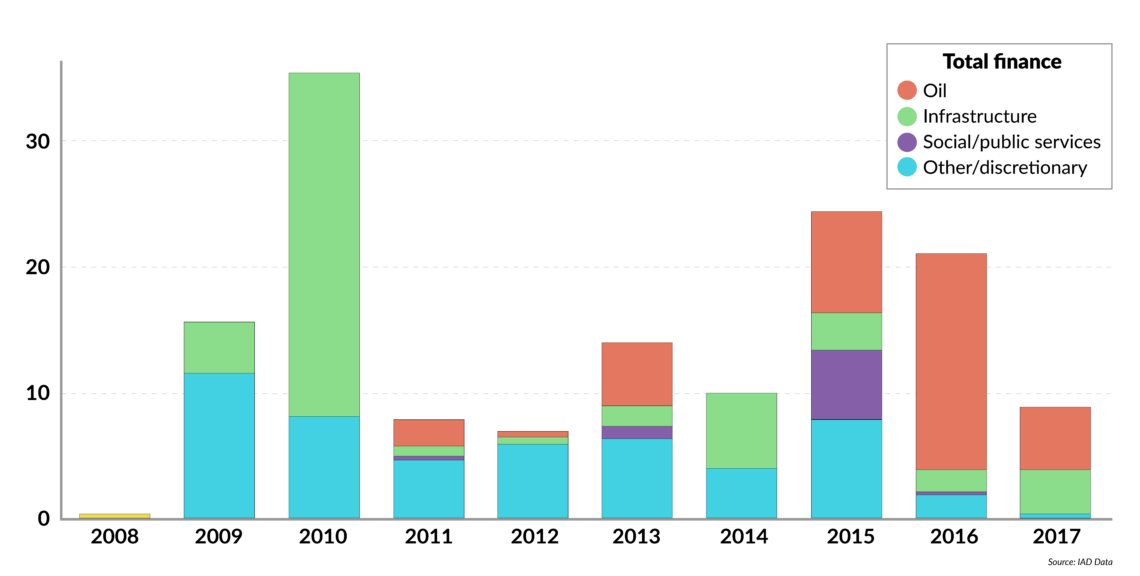

The difference, however, is that from the beginning, Ecuador could not produce nearly as much oil as Venezuela. To guarantee production, the Chinese quickly expanded from petroleum to infrastructure investments. Now, Mr. Correa is out of power and the new administration is not sure it is comfortable having the country’s oil mortgaged to the Chinese. To cover its position in oil, the Chinese have doubled down on their investment in infrastructure. Today, virtually all infrastructure development in Ecuador is a product of Chinese investment.

Facts & figures

Chinese bank loans to Latin American and Caribbean governments

By sector, 2013-2017

Brazil

The Brazilian case is entirely different from any of the others in Latin America, even though it too began with trade in commodities as well – in this case for soybeans. China is the largest buyer of soybeans in the world and Brazil is the largest exporter of the commodity, having just replaced the U.S. in that position in 2017. Argentina is the third-largest exporter, far behind Brazil and the U.S. Brazil also can produce significant amounts of petroleum for export, not to mention other strategic raw materials, such as iron, if it could get its political house in order.

Over the past two decades, the price of soybeans has fluctuated significantly, from a low of $4.40 per bushel in 2001 to $17.40/bushel in 2012, and then back down to less than $9/bushel today. Throughout this period, China has bought vast quantities of soybeans, while its companies have made direct investments in the soybean production chain, including land, processing plants and companies that export. The Chinese have also loaned $5 billion to the Brazilian national petroleum company, Petrobras, and have made investments downstream in the Brazilian energy grid. China is a prized trading partner and valuable ally for Brazil, while its presence in the country stirs little or no anxiety. Brazil’s economy, after all, is the seventh-largest in the world, so Chinese activity does not have such a high profile there as it does in Chile, Ecuador or Venezuela.

Facts & figures

China's share of Latin American and Caribbean exports

By major sector, 1996-2016

Cuba

The only other individual country case worth mentioning in a discussion of China’s role in Latin America is Cuba. Beginning in the Cold War, Cuba turned to the Soviet Union and to China for support in dealing with the embargo imposed by the U.S. With the collapse of the Soviet Union, Russia has not had the resources to be of much help and China has been reluctant to step into a complicated situation. For a while, Hugo Chavez was able to help the Castro regime with cheap oil. The Maduro government has attempted to continue that aid. However, the collapse of Venezuelan production has made it difficult for President Maduro to maintain Venezuelan largesse with Cuba.

The Cubans have tried to persuade the Chinese to fund the construction of a deepwater port on the island and to provide some form of financial support. Beijing has shunned the role of lender because of Cuba’s dual currency regime, which, in the absence of any commodity export such as oil, would make recovering their investment very difficult. Given the Trump administration’s hostility to the Cuban government, the Chinese have decided that they will remain on the sidelines for now.

Positive impression

Aside from these individual country cases, China has burnished its role as a partner in the development of the region through its new development bank, the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB). Most Latin American countries have joined the bank, and it has already made loans in the region. In fact, if the AIIB’s Latin America portfolio continues to grow at the rate it has for the past two years, it will match or exceed that of the Inter-American Development Bank, the region’s Bretton Woods Institution, in less than a decade.

Latin American producers export three times more to the U.S. than they do to China.

The other way in which China is making a positive impression in Latin America is its willingness to participate, as an investor or lender, in the region’s large infrastructure projects, such as the Interoceanic Highway. This is right up China’s alley, following the pattern it is setting in its Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) in Eurasia. Just a few years ago, China was ready to partner with Brazilian construction giant Odebrecht in building the Bi-Oceanic Railway. However, that project has never gone beyond the drawing board, partly because of political instability in Brazil and Peru, as well as the huge corruption scandal that bankrupted Odebrecht.

One final point on perspective. While Chinese foreign direct investment (FDI) is significant in Latin America, it is only 10 percent of China’s total investment overseas. Chinese FDI is a pittance compared to the stock of U.S. investment in the region, and a tiny fraction of total world FDI, which in 2017 stood at $1.4 trillion. Moreover, Latin American producers export three times more to the U.S. than they do to China. And when it comes to soft power, China’s influence is negligible, compared to that of the U.S. These factors will influence Chinese policy decisions. In the last few years, Chinese state-run news agencies Xinhua and People’s Daily have established Spanish-language operations, which have served as pseudo-news/propaganda for Beijing’s activities in the region.

Scenarios

The central question is how intrusive or aggressive China wants to be in Latin America. The answer depends on how its relations evolve with the U.S. and India. The most likely scenario is that China will work to avoid further commitments in Venezuela and Ecuador, and try to keep out of the spotlight. Bullying Chile into allowing a Chinese takeover of SQM would upset the countries in South America, but it is highly unlikely to provoke a response from the U.S. If Venezuelan oil production continues to decline, look for China to invest more money in Petrobras.

Although far less likely, it is possible over the next few years that China may seek to provoke the U.S. by tweaking President Trump’s nose. To do that in Latin America would require getting more involved in Cuba or Venezuela, which Mr. Trump’s hawkish advisors would consider an actionable offense.