The Tajikistan factor

Worried about the regional instability that Taliban rule over Afghanistan may bring, China has plenty of reason to ramp up its military activity in Tajikistan. With the increased risk of extremist activity on its Western border, Beijing could begin flexing its muscles more overtly.

In a nutshell

- Tajikistan’s long border with Afghanistan makes it vulnerable

- China and Russia worry about terrorists in their backyards

- Both already have military contingents in Tajikistan

The United States’ chaotic withdrawal from Afghanistan will produce long-term effects that last well beyond the Biden presidency. It has been understandably hard for political elites in both Russia and China to avoid displays of glee at the humiliation of the American superpower. However, that glee will soon be followed by a rude awakening.

As Afghanistan reverts to its deeply ingrained patterns of clan-based rule, it is not just the country’s urban elite and those who worked for the Americans who will be left high and dry. The other great powers will face serious challenges in adjusting to the U.S. withdrawal.

Many uncertainties remain about whether the Taliban have really disassociated themselves from Islamic State (also known as ISIS or Daesh) and whether they will be able to act independently of their presumed protectors within the Pakistani intelligence services. At the core of such questions lies whether the Taliban movement itself is coherent enough to avoid significant infighting.

Priorities in jeopardy

In this regard, China will face an especially difficult challenge. While Russia under President Vladimir Putin has shown little sign of strategic planning beyond ensuring that Mr. Putin remains in power, China under Xi Jinping has developed a clear road map for its future development, with plenty of funding set aside to achieve those goals. The Taliban takeover of Afghanistan could throw a wrench into many of those plans.

China worries that the Taliban will provide safe haven for insurgent groups.

Beijing has two core priorities for the region, both of which are now in jeopardy. One is to ensure that jihadist influence does not spread into its westernmost province of Xinjiang. It has gone to great lengths to keep the Uighur Muslim minority there from becoming radicalized. In doing so, it has paid a substantial price in deteriorating international relations, both with the West and with important neighboring Muslim countries like Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan. Now, China worries that the Taliban will provide safe haven for insurgent groups like the East Turkestan Islamic Movement (ETIM), which wants to take over Xinjiang.

During a meeting in late July with Taliban cofounder Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi expressed hope that the movement would make a clean break with all terrorist organizations, including ETIM. The response from the Taliban was its routine pledge not to allow any organization to threaten Afghanistan’s neighbors from its territory. But many doubt the sincerity of such statements.

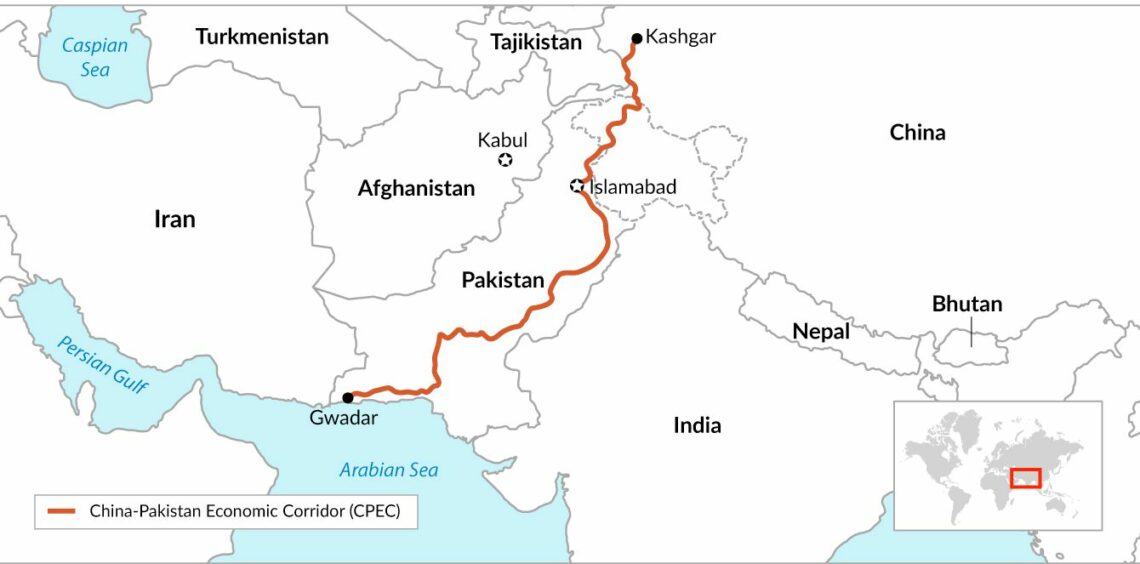

Beijing’s other priority concerns the rollout of the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), the flagship global infrastructure investment program and brainchild of President Xi. It has invested heavily in an economic corridor from Kashgar in Xinjiang to Islamabad in Pakistan and onward to the port of Gwadar, on the Arabian Sea. From there, Chinese exports will have access to the Indian Ocean and Western markets.

Facts & figures

Beijing also hopes to develop an additional BRI route through Uzbekistan and Afghanistan. The Uzbek government has banked heavily on being able to work with the Taliban to build a transport artery of pipelines and railroads through Afghanistan, from Mazar-i-Sharif to Kabul and onward to Pakistan. Islamabad, like Beijing, has received security guarantees from the Taliban.

Tajikistan’s importance

Tajikistan plays a crucial role in these scenarios. It is a small, mountainous republic bordered by Uzbekistan and Kyrgyzstan to the north, China to the east and Afghanistan to the south. Beijing has good reasons to ramp up its security cooperation with this otherwise rather insignificant neighbor. One concerns the 1,357-kilometer border between Tajikistan and Afghanistan. It meanders through remote, mountainous terrain where border guards have long been waging a losing battle against the narcotics trade. Both Russia and China worry that the Taliban takeover of Afghanistan will result in waves of refugees that allow terrorists and jihadists to infiltrate Tajikistan and operate in their backyards.

The Kremlin’s main fear is that the inflow of people could destabilize Uzbekistan, which has a long history of combating Islamist insurgents. While the short border between Uzbekistan and Afghanistan may be reasonably easy to patrol, the one between the latter and Tajikistan presents a much bigger challenge. In addition to beefing up its military presence there, Moscow believes that cultivating good relations with the Taliban will provide added security. Russia’s special envoy to Afghanistan, Zamir Kabulov, says Moscow has been working to establish contacts with the Taliban movement for seven years.

While Beijing shares Russia’s worries about destabilization in Uzbekistan, its own fear that ETIM insurgents could filter into Xinjiang is much greater. It therefore sees a critical need to provide security in the Tajik border areas.

If Taliban rule breaks down, the northern part of the country will fall into Tajik hands.

With some 42 percent of the total population, Pashtuns are the largest ethnic group in Afghanistan. But the Tajik minority accounts for over a quarter of the country’s inhabitants. While the Pashtuns dominate in the south, the Tajiks dominate in the north, and are also influential in the capital, Kabul.

The implication is that if Taliban rule breaks down and Afghanistan again descends into sectarian violence, then the northern part of the country will be in Tajik hands. Tajiks and Pashtuns have a long history of animosity. When the Taliban were in power in 1996-2001, the north remained under the control of the Northern Alliance, whose subsequently murdered leader, Ahmad Shah Massoud, was a Tajik. That legacy is very much alive.

During the recent battle for the Panjshir Valley, the last stronghold against the Taliban, resistance was led by Ahmad Massoud, the son of Ahmad Shah Massoud. There are reports that Tajikistan may have used helicopters to provide military equipment, weapons and other supplies to the resistance. Other reports suggest Pakistan provided intelligence in support of the Taliban advance.

The government in Tajikistan has been keen to ensure that Pashtuns do not take complete control of Afghanistan. During an August 25 meeting in Dushanbe, Tajik President Emomali Rahmon told visiting Pakistani Foreign Minister Shah Mahmood Qureshi that his country would not recognize a government “created by humiliation and ignoring the interests of the people of Afghanistan as a whole, including those of ethnic minorities, such as Tajiks, Uzbeks and others.”

Security buildup

Another reason for China to take a serious interest in Tajikistan is that it is a place where the Sino-Russian partnership is being tested and found wanting. In the broader tussle for influence in Central Asia, Russia and China have a long-standing agreement on a division of roles that leaves security to the former and economic development to the latter. But in Tajikistan, there has been little to no cooperation on the ground.

Facts & figures

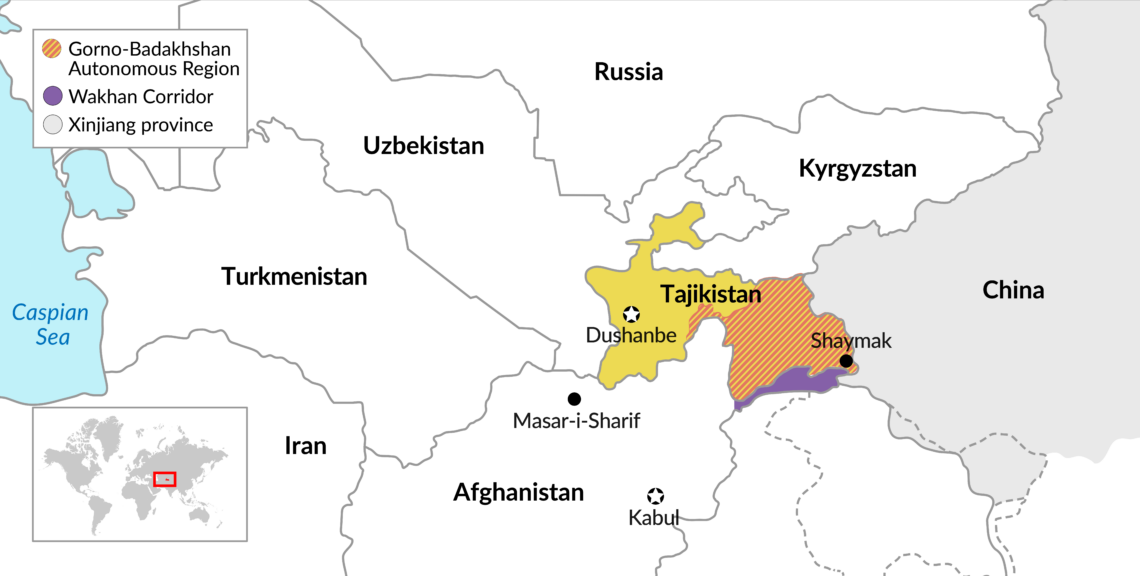

The Russian garrison in Dushanbe, home to the 201st Motor Rifle Division, is its largest military base outside Russia. But it is located in and mostly concerned with the western part of the country. In the eastern Gorno-Badakhshan Autonomous Region, which borders both China and Afghanistan, Beijing is taking security into its own hands.

China has not limited its increased security cooperation to providing hardware and training to improve Tajik border control. In 2016, it also broke with prior practice by establishing a military base in a foreign country. A People’s Armed Police force is now based at Shaymak, where the borders of China, Tajikistan and Afghanistan meet. And Beijing spearheaded the creation of the Quadrilateral Cooperation and Coordination Mechanism, which brings together top military staff from China, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Tajikistan.

The Chinese’s main concern is the Wakhan Corridor, a narrow strip of Afghan territory wedged between Pakistan and Tajikistan that terminates at the border between China and Afghanistan. Although the Chinese-Afghan border is only about 76 kilometers, Beijing worries that jihadists could use the much longer border between Wakhan and Tajikistan to slip into the latter. Previously, China conducted joint patrols with Tajik and Afghan forces to prevent that from happening. With the Taliban in control of Afghanistan, that is no longer possible.

Carrots and sticks

The outlook hinges on whether foreign powers can buy the Taliban’s cooperation. On September 9, China announced an introductory $31 billion package of desperately needed emergency aid to Afghanistan. The incentives go far beyond food and medical aid, and help in rebuilding. The real prize would be massive infrastructure development that entails not only pipelines and railroads, but also power transmission and water supply.

If the Taliban prove unable to provide security for Chinese projects, Beijing will pull back and focus on Pakistan.

If the Taliban prove unwilling or unable to provide security for such projects, then China will pull back and focus on Pakistan, where it already has enormous investments. It will concentrate on protecting those projects, since the Pakistani Taliban have vowed to attack Chinese interests. All this raises the question of whether Beijing can convince Islamabad to dial back its support for the Taliban. The Chinese will put considerable pressure on Pakistan to do so, but it is unclear whether the Pakistani government has enough influence in tribal areas to reduce Taliban operations there.

The core of the challenge is that the Taliban movement is a conglomerate of highly diverging interests, with hazy ties to both Islamic State and al-Qaeda. It is difficult to know with which faction you are striking a deal.

Scenarios

China will continue its strategy of co-opting local forces into protecting its interests abroad. It may enhance this approach by working more closely with Tajikistan, and perhaps even by resorting to the use of private security companies, as the U.S. with Blackwater, or the Russians with the Wagner Group. But in the face of serious instability, even that approach will come up short.

It may be tempting to speculate, as some influential American politicians do, that one day the U.S. will be forced to return to Afghanistan. That comeback could involve support from Tajikistan (and China) in revitalizing the Northern Alliance. Yet the likelihood of this scenario is extremely low, and not only because the rapid U.S. withdrawal handed the Taliban some $85 billion worth of American military equipment.

An equally important question is whether the Afghan Tajiks would be loyal to the government in Tajikistan. Although the majority vehemently reject the Taliban, many have joined its ranks. The Taliban, for its part, may have links to radicals within Tajikistan that want to establish an emirate of their own.

The most likely outcome is that the great powers face complex, multifaceted conflict where at times each side is pitted against the other, where the fog of battle is dense and where friends cannot be distinguished from enemies. In this scenario, Pakistan may begin to have second thoughts about protecting the Taliban.