The future of the U.S.-China nuclear arms race

The bilateral competition will intensify as China seeks nuclear dominance and other competitive advantages over the United States.

In a nutshell

- China’s buildup calls into question the adequacy of America’s missile defenses

- Other nations, both U.S. friends and foes, may seek to join the nuclear club

- In this heated atmosphere, arms control agreements will not be successful

There is already a nuclear arms race between the United States and China. It is fueled by China’s determination to reach true great power status, with strategic influence on par with what was achieved by the U.S. and the Soviet Union during the height of the Cold War, when both superpowers gained the capacity for mutual assured destruction. China’s quest for nuclear dominance complements other initiatives intended to give Beijing decisive advantages against the U.S., and to hedge against the uncertain future of Russia in the wake of its war against Ukraine. This competition will likely accelerate for a decade or more.

Red missiles on the rise

The Chinese spy balloon that recently traversed North America – which the U.S. has publicly stated was a surveillance craft for gathering Signal Intelligence (SIGINT), and likely MASINT or Measurement and Signature Intelligence – was probably seeking to learn about the U.S. early warning and nuclear capability and command and control. This incident coincided with an admission by U.S. government officials that China has likely surpassed the U.S. in the number of nuclear-capable, land-based Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) launchers. These events have renewed attention on the emergence of China as a pivotal nuclear power. By unclassified estimates, China nuclear-armed strategic missile force will likely in the near-term match or exceed either the U.S. or Russia.

China’s missile force already exceeds the capacity of U.S. missile defenses to intercept incoming ICBMs targeting the U.S. mainland. In addition, China, according to unclassified estimates, has the capacity to simultaneously engage countervalue (U.S. cities) and counterforce (the U.S. first strike nuclear capability).

Changing the face of nuclear war

As China’s force grows, this introduces several new dynamics in nuclear competition.

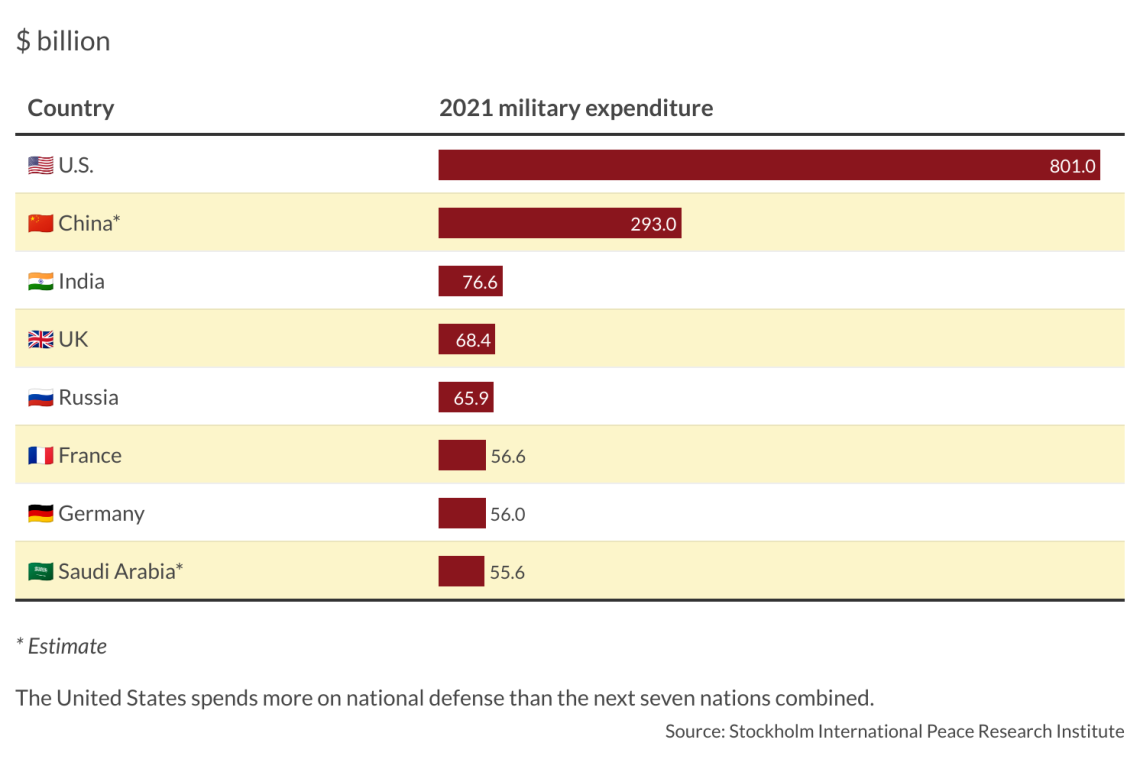

U.S. strategic nuclear forces are sized and targeted to deter Russian nuclear forces and limited others. The U.S. likely does not have sufficient capability for “mutually assured destruction” with both Russia and a better-armed China simultaneously.

The efficacy of the American nuclear umbrella, or extended deterrence, could be cast into doubt. Extended deterrence means safeguarding allied nations from the threat of nuclear retaliation if they are attacked. For example, NATO and treaty allies like South Korea and Japan are included under the nuclear deterrent. Having a robust first-strike capability against the U.S. raises questions such as “would the U.S. risk nuclear war and losing cities like Washington and New York to defend Estonia – or Taiwan?”

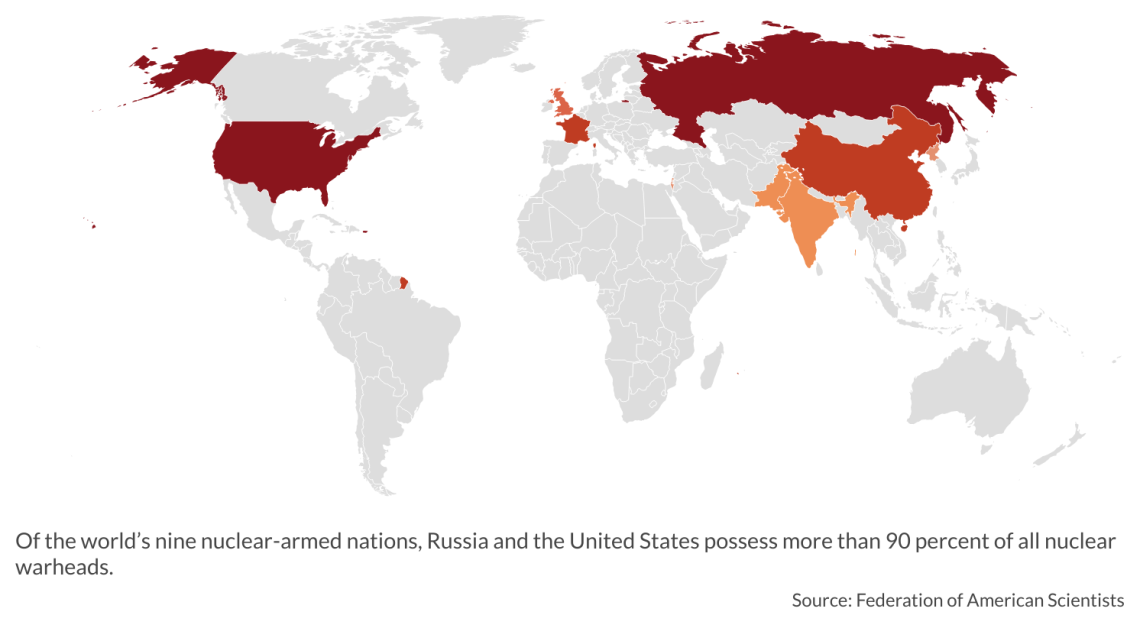

As China’s nuclear umbrella grows, would China encourage more nuclear proliferation? Would China support a nuclear Iran? On the other hand, the magnitude of the Chinese nuclear threat may trigger nations allied or friendly with the U.S. to develop an independent nuclear deterrent, as France and the United Kingdom did during the Cold War. Will we see a nuclear South Korea or Japan or new nuclear powers in the Middle East?

Facts & figures

Future U.S. actions

After the Cold War, the U.S. had scant interest in conducting nuclear testing or building new nuclear weapons. The U.S. focused almost exclusively on maintaining its existing arsenal, as well as modernizing platforms as needed. Washington also developed missile defenses, albeit focused on dealing with North Korea and a potential Iran threat, not to counter Russia or China.

Under President Barack Obama, the administration dabbled with the “road to zero” initiative, voluntarily reducing American dependence on nuclear deterrence. Over the course of his presidency, Mr. Obama abandoned the concept as unworkable. He placed renewed emphasis on arms control agreements while also acknowledging the importance of maintaining the strategic stockpile and platform modernization including a new bomber and nuclear submarines.

Since assuming the presidency, Joe Biden has sought to replicate the Obama policy, reengaging in arms control agreements with Russia and maintaining its weapons arsenal, while rejecting proposals to develop a new generation of sea-launched nuclear cruise missiles.

The U.S. strategy virtually ignored the prospects of a rapid expansion of China’s nuclear forces, which was only recently publicly acknowledged. American officials have stated that China’s ballistic launcher missile force is no larger than that of the U.S.

State of play

The chances for limiting nuclear arms competition through arms control agreements are zero. The U.S. recently declared that Russia is not in compliance with the recently extended New START Treaty, the last major nuclear arms treaty between the U.S. and Russia. While Russia is embroiled in the war with Ukraine, it is unlikely that Moscow – which has suspended participation in the agreement — will ever allow inspections that would put the country in full compliance with the treaty. Meanwhile, China has been very clear that it has no interest whatsoever in an arms control regime with the U.S.

Facts & figures

Scenarios

Where do we go from here?

Russia, because of the significant degrading of its conventional forces as a result of the war with Ukraine, will most likely place increasing reliance on its strategic deterrence to sustain its great power status. In the improbable advent that the Russian government collapses, the nation could devolve into seven or more entities, and perhaps three might become independent nuclear-armed states, reluctant to relinquish custody of the weapons to Moscow.

It is extremely unlikely that China will curb its nuclear ambitions or engage in serious arms control. In addition to expanding its first-strike capability, China will continue to seek to expand its influence in controlling coastal waters, establishing sanctuaries for its diesel-powered nuclear-armed submarines where they are protected from U.S. anti-submarine warfare capabilities.

Meanwhile, as China builds up, argues Patty-Jane Geller, a nuclear arms expert at the Heritage Foundation, “the U.S. will need a nuclear force that can credibly convince China that the costs of using nuclear weapons would exceed the benefits.” This will result in increasing bipartisan pressure for “boosting procurement plans for nuclear modernization programs already under way, including for the Sentinel missile, Columbia-class submarine and B-21 bomber,” Ms. Geller argues. In addition, there will be a push to accelerate developing and deploying a submarine-launched cruise missile.

There is an arms race. The question is whether the competitors will reintroduce doctrines of mutually assured destruction, or opt for an offense-defense mix of an assured second-strike capability and more robust missile defenses to deter by demonstrating the capacity to survive and mitigate a nuclear attack.