In Western capitals, shifting attitudes on China

Washington and Europe’s major capitals are taking a more critical view of China, and concern about the implications of Chinese investment is on the rise. The question is whether these governments can align their policies to formulate a coordinated response to the challenges posed by China’s rise.

In a nutshell

- Germany, France and the UK are all worried about increasing Chinese influence

- Washington sees China as a rival whose strength is growing

- Their approaches are all different, and it may be unable to reconcile them

- China will likely be able to continue to flout the international, rules-based system

Views of China in Washington and Europe’s major capitals are becoming more critical. The Europeans are increasingly concerned about the impact of Chinese investments, issues of reciprocity and the distortions that China’s state-capitalist economic model imposes on the international system.

Washington, meanwhile, has similar concerns (along with others, like political/security issues) and is becoming much more assertive in addressing them. The degree to which Europe and the United States can bring their collective strengths to bear on behalf of the rules-based international order depends on reconciling key differences in their approaches.

Berlin

Germany is China’s partner of choice in Western Europe for several reasons. The first is its renowned industrial prowess, from which the Chinese can learn. Second, Germany is an open investment environment, allowing the Chinese to harness some of that German industrial power for itself. Third is Germany’s leading role in the European Union, which Beijing can use to finesse the EU system.

China’s economic interest in Germany is borne out in the numbers. According to the American Enterprise Institute/Heritage Foundation China Global Investment Tracker, Germany is the third-largest destination for Chinese investment in Europe. Most of that goes into industry, and some of the highest profile investments, like in robotics company Kuka or the automaker Daimler, have raised concerns in Germany. Even failed bids, like an attempt to acquire the semiconductor equipment company Aixtron, have contributed to German anxiety about a Chinese takeover of its industry.

The Germans may be concerned about Chinese investment, but the economic opportunities frame their policy choices.

The German government is pushing back with calls for a better Chinese investment climate and new investment screening, both at the national and EU level. But the contentiousness must be kept in perspective; after all, China is Germany’s largest trading partner. Germany is also one of China’s top 10 investors and is seen by many companies, such as those in the auto sector, as a critical source of future growth. As concerned as German authorities may be about Chinese investment at home, the economic opportunity presented by China continues to frame their policy choices.

The above-mentioned benefits to China give Germany some leeway for its gentle involvement on some sensitive matters like human rights, Tibet and Taiwan – something other European powers do not have. And although the Chinese may seek to use Germany to influence the EU, Germany is very protective of the integrity of EU processes. It has also has been a leader in the bloc on some difficult issues, including the South China Sea. Still, Germany is very cautious and committed to working through its differences with China via extensive consultations.

Paris

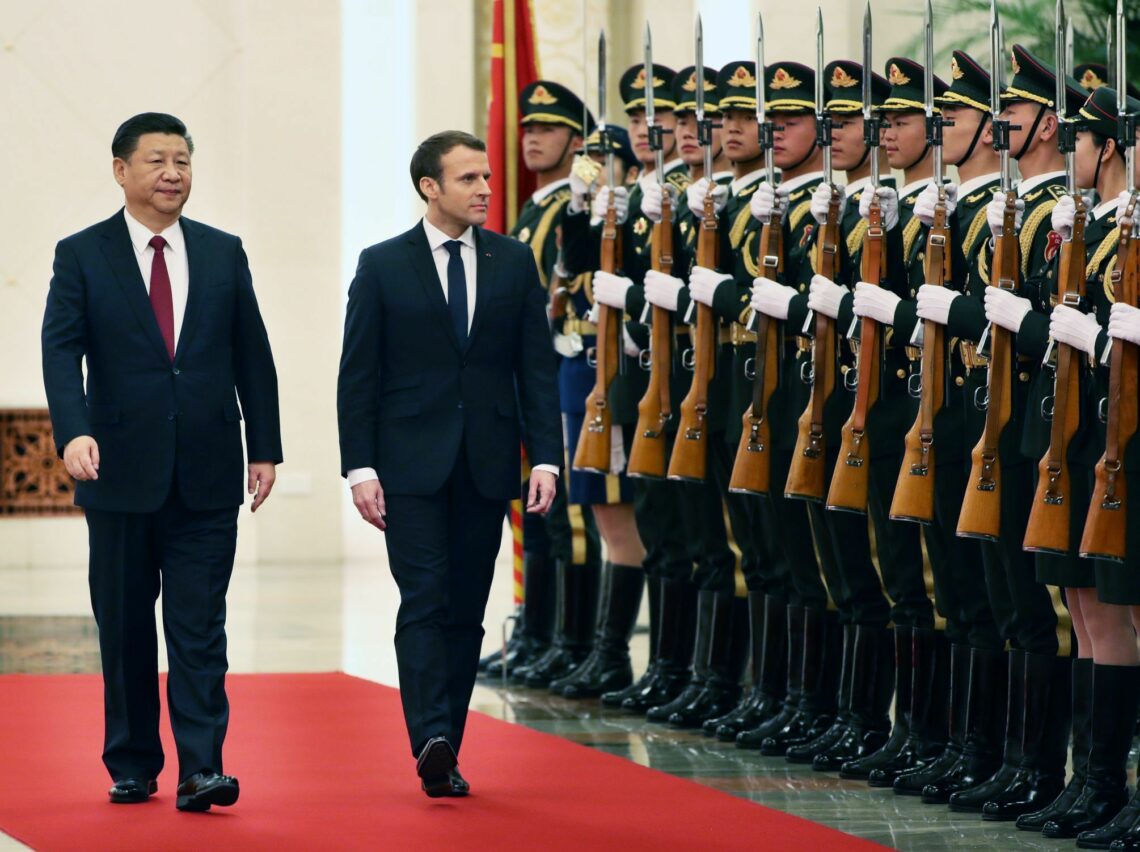

The French also have major economic interests in China and a relationship that, like Germany’s, is officially weighted toward cooperation and dialogue. French policymakers are very concerned about the strategic intent of China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI). In fact, French President Emmanuel Macron’s speech in Xi’an during his first visit to China drew a considerable amount of attention for his admonition that the BRI cannot be “one way.”

But many ignored the fact that the comment was only a small part of an overwhelmingly positive speech about China’s contributions to the world and the great potential for Franco-Sino relations. A similar dynamic was on display during Mr. Macron’s visit to Australia, about which the headlines focused on his call for a new Indo-Pacific Axis; less attention was paid to caveats that the call had nothing to do with China.

That said, unlike Germany, France’s relationship with China is complicated by its regional presence, particularly in the South Pacific. France’s territories there and its related maritime interests make China’s challenge to customary international maritime law more than simply a theoretical problem. This challenge, accompanied by the rise of Chinese influence in the South Pacific, compels France’s active involvement. From 2016-2017, France deployed ships to the South China Sea 10 times to demonstrate international rights in these waters. It is the most active European power in this regard.

Further complicating the relationship, France’s national security establishment has come to see China as “a power with global ambitions … striving to become the dominant power in Asia in the near future and, in the long term, to match or overtake the power of the United States.” That statement, from its 2017 National Security Review, contrasts sharply with its 2013 white paper in how clearly it identifies the challenge.

As valuable as France’s relationship with China may be, and as fractious as its relationship with the U.S. can sometimes be, the prospect of the region being dominated by China is a powerful incentive for closer cooperation with Washington in the Indo-Pacific.

London

Concerns about China’s strategic designs are becoming clear in capitals across Europe. But while the United Kingdom’s enthusiasm has been tempered by these considerations, it continues to frame its relationship with China in terms of the “Golden Era” initiated in 2015.

Last winter, British Chancellor of the Exchequer Philip Hammond visited Beijing. During meetings there, the two sides reportedly agreed to “72 outcomes,” including cooperation on China’s BRI projects. The public centerpiece was a $1 billion bilateral private equity investment fund, headed by former Prime Minister David Cameron, to support projects in China, the UK and third countries targeted by China’s BRI. During her own visit to Beijing the following month, Prime Minister Theresa May declined to officially endorse the BRI, for China’s lack of commitment to international standards, but the UK is already deeply invested in the concept.

The UK is home to a far greater stock of Chinese investment than either Germany or France.

The UK is home to a far greater stock of Chinese investment than either Germany or France. A third of deals made between 2000 and 2016, according to the European Think-tank Network, has been in the real estate and hospitality industries. Most of the rest – including from the controversial government-connected corporation Huawei – involve investments in information technology. Beyond these areas, the most prominent is the state-owned China General Nuclear Power Corporation’s investment stake in the French-led construction of a nuclear power station at Hinkley Point.

Uncertainty over the impact of Brexit and the need to create a new network of formal trading relationships has put a greater premium on the economic potential of UK-China relations. Direct British interests in the Indo-Pacific are not great enough to risk this potential. The British have the territory of Diego Garcia in the Indian Ocean, which is leased for use by the U.S. military, a legacy interest in the future of Hong Kong to which they have shown little commitment since the city’s turnover to China. They also have a standing commitment to the Five Powers Defense Arrangement – a marginal element of the region’s security architecture. None of these have given the UK much real interest in physically challenging Chinese assertions of extra-legal rights in international waters.

Washington

Under President Donald Trump, the U.S. has adopted a great power competition approach to China. The description of the challenge was explicit in its 2017 National Security Strategy (NSS). America’s “rivals,” including China, “compete across political, economic, and military arenas, and use technology and information … to shift regional balances of power in their favor” and “shape a world antithetical to U.S. values and interests,” according to the report.

In response, the U.S. is rebuilding its military, reasserting its military presence in the region and moving to protect its defense industrial base, liberally defined. The NSS also calls for strengthening an already robust system of alliances and security partnerships in the Indo-Pacific. Moreover, it lays out a case for “competitive diplomacy,” including greater use of economic tools like “fair and reciprocal” trade agreements and sanctions. Under this strategy, the economy is an inseparable part of America’s national power; it must be mobilized for the U.S. to successfully compete and it must be protected from Chinese designs.

The Trump administration has been willing to risk the economic relationship for the broader strategic challenge.

The U.S. has major economic stakes in its relationship with China. Its companies make it the third largest investor in China – bigger than Germany, France, or the UK. China is America’s largest trading partner and third largest export market. Imports from China are also critical to the American economy, providing intermediate goods to manufacturers and finished products to consumers. The story of the Trump administration on trade, however, has been a willingness to risk the economic relationship for the cause of the broader strategic challenge and the demands of domestic economic constituencies.

Scenarios

More likely

Assuming China’s current position remains the same – that is, it continues to grow in global clout and aggressively pursue its core interests, including sovereign control over the South China Sea – there are two ways that the policy approaches of Germany, France, the UK and the U.S. can combine.

The most likely scenario is that each country continues to muddle through their respective approaches to China with little effective coordination. Each European capital, along with Brussels, will focus most intently on their economic interests vis-a-vis China, with only occasional friction that will be downplayed whenever it does occur. On the other hand, the U.S., under Mr. Trump, will continue its more assertive approach, generating greater friction in its own relationship with China.

The U.S. will attempt to rally European capitals to its strategy, but because of broader issues of trust with Washington and because the Trump approach to trade also often targets Europe, it will fail. More fundamentally, it will fail because the Europeans are generally less willing than the Trump administration to sacrifice economic benefits for geopolitics.

In this scenario, the EU will make a separate peace with China on economic issues. The Europeans will continue to have concerns with reciprocal market access and the BRI’s strategic designs. Occasionally they will make common cause with the U.S. concerning Chinese market abuses; at other times they will defend international economic institutions like the WTO against American derogations.

Otherwise, they will deal with their differences with the Chinese through dialogue and by tweaking European investment regimes, all the while pursuing China as a global investment partner. Divided among themselves and making money, the Europeans will make little progress on their systemic concerns. Chinese influence in Europe will rise.

Over time, Europe’s wherewithal to resist Chinese violations of global trade and investment regimes will diminish. Consequently, those regimes will weaken and the relative strength of China’s alternatives to them will grow.

On political/security issues, the Europeans will accommodate the Chinese. They will find it increasingly difficult to support other elements of the rules-based order, such as freedom of navigation. France, which on these issues is the most forward-leaning in Europe, will continue to assert its rights to navigation in the South China Sea. The Chinese will complain about French activity, but, confident in their long-term position, they will accept it as a matter of little consequence.

Others in Europe will find it advantageous to stay on the sidelines. With the U.S. and Europe uncoordinated on these and other issues, the Chinese will be emboldened to unilaterally secure their core interests. This will either lead to conflict with the U.S. in the short term or in the U.S. abandoning its commitments in the region in the longer term.

Less likely

The less likely scenario is that Europe and the U.S. find ways to effectively coordinate their strategies toward the Indo-Pacific. This will require the alignment of several factors.

The first and easiest is the alignment of official strategies. As noted above, France’s National Security Review has some points in common with the American NSS, but they come from very different perspectives. French Indo-Pacific strategies, to be released later this year, could help narrow those differences and pave the way for greater tactical security cooperation.

The UK has a more robust security relationship with the U.S. than France, but its strategy toward China is more conciliatory. This scenario would require a better meeting of the minds between the U.S. and the UK, and a real material commitment to the region by the British military in a way that matches the French contribution.

The second factor is the place of the economy in strategy. The U.S. will have to develop a strategy that incorporates a more complex approach to the role that economics plays in international relations. The political and the economic operate by two different paradigms; the former is dominated by states, while the latter by global value chains and international finance.

China’s state-led economy challenges this delineation, but both American businesses and European governments will resist putting business interests at the disposal of the state to respond. Separating out geopolitics and addressing economic issues – such as steel overcapacity and intellectual property theft – will narrow the scope of cooperation and thereby facilitate it. Removing economic impacts from foreign policy will also facilitate cooperation on political issues.

The third factor revolves around trust. Some of the Trump administration’s sharpest differences with Europe have softened over the last year. Mr. Trump’s views on NATO, for instance, which were once considered up in the air, have settled into a more traditional pattern. Inconsistent policy and communication from the Trump administration, however, continues to stoke uncertainty in Europe.

As long as the U.S. cannot consistently reassure the Europeans of a common cause on issues closer to home – such as on Russia, Iran and the Middle East – it will be difficult for them to put stock in common causes half a world away. For their part, the Europeans must see the continuities in U.S. foreign policy, especially in the Indo-Pacific, where there are far more similarities than differences with previous administrations, and put greater trust in American institutions.

With these three factors more closely aligned, European capitals and Washington will be better able to work toward preserving the rules-based order they say they care so much about and address the challenge the Chinese pose to it.