A tipping point for climate change activism

The climate change debate is nearing a fork in the road: governments will either succumb to the alarmist pleas of activists, or turn to sober measures enabling long-term shifts.

In a nutshell

- Environmentalists are issuing ultimatums on climate change

- Sweden shows the tensions facing green technology

- Sustainable solutions can be found in scientific discoveries

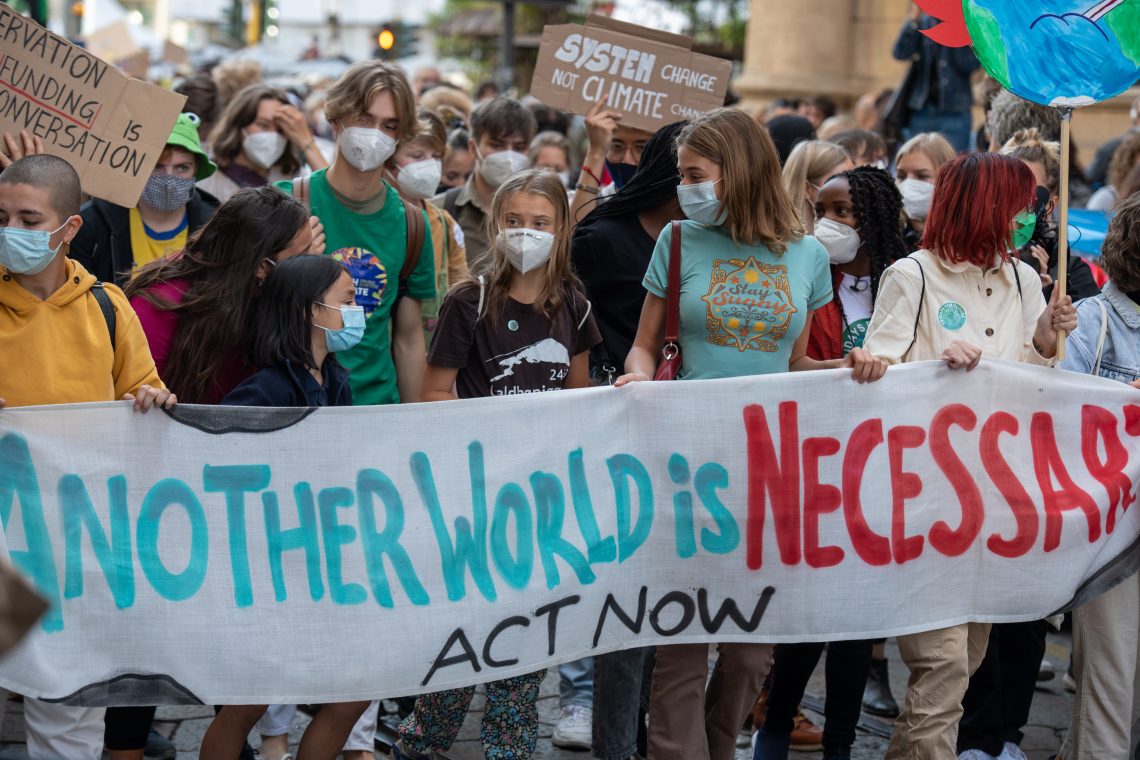

Climate change activists have long sounded dire warnings of a world headed for climate disaster. Key to these predictions is the notion of a “tipping point”: a juncture when drastic action must be swiftly taken to prevent a global catastrophe before it is too late.

The thinking is easy enough to understand. Activists concerned about global warming become frustrated by perceived government inaction, and may be tempted to compete over who can be the most radical. Meanwhile, advocacy groups that thrive on media attention have little incentive to present nuanced accounts.

In reality, the process of climate change has already had sufficiently negative consequences to be taken seriously – without predictions of sensational outcomes like a reversal of the Gulf Stream or a six-meter rise in sea levels. And importantly, there is no scientific backing for arguments of a point of no return.

The worst-case scenarios will bear out for the extinction of certain species, and some island nations do have grounds to worry about being irreversibly flooded by rising sea levels. But it goes too far to warn of a fast-approaching moment after which deeply harmful processes like deforestation can no longer be reversed. It is symptomatic that the supposed point of no return is regularly postponed.

That said, the concept of a tipping point may still be productive in the climate change debate. The appeal to haste cuts both ways: either we must ramp up pressure on governments to take drastic action in the short term, or we need to curb sensationalism and allow room for science to respond with discoveries that are effective in the longer term.

Engineers or activists?

The key question is whether political pressure from below is helpful or not – or perhaps even harmful. In this context, the real “tipping point” may be a time when radical activism forces governments into desperate, short-term actions that undermine prospects for sustainable solutions. Experience from Sweden suggests that this moment may already be at hand.

As a technologically advanced nation with green interests well-represented in national politics, the country has made two important contributions. One is cutting-edge technology to produce “fossil-free” steel without releasing greenhouse gases; the other is teenage activist Greta Thunberg. The contrast between the two highlights the core of the problem – namely, whether we need more engineers or more activists.

The case for more engineers assumes that a long-term solution to global warming can be found only by developing new technologies to produce and utilize clean energy. Government action to force people to change their habits may be helpful and even necessary in some contexts, but will not be decisive.

The surprising development of increasingly effective vehicle batteries has shown what science can achieve in efforts to address climate change.

The Covid-19 pandemic has helped show that while regulated behaviors like social distancing and other lockdown measures can help curb infection spikes, only vaccination can provide a long-term fix. Science surprised many experts by producing effective vaccines in record time, which should give us grounds for optimism about climate change.

Given the role of combustion engines in driving greenhouse gas emissions, the rapid proliferation of electric cars has been encouraging. As with vaccines, the rapid development of vehicles using increasingly effective batteries has been a positive surprise, emphasizing what science can achieve.

The Swedish case

Yet, unless electric cars can be powered by clean energy, expanding their use will not be very helpful. Burning dirty coal to produce electricity to charge car batteries will at best produce an illusion of progress. This is where the Swedish example is again relevant, showing how climate activists in government may undermine the prospects for real solutions.

Before the green agenda became dominant, Swedish power generation was almost fossil-free, drawing about half from nuclear sources and half from hydro sources. Only on extremely cold days would an oil-burning power plant (at Karlshamn) be used, and natural gas not at all. On this foundation, one could have envisaged bright prospects for a carbon-free future.

The production of fossil-free steel illustrates how science and technology may lead the way. Aside from forestry, the mainstay of Sweden’s development as a modern industrial nation was imported coal and domestically mined iron ore, combined to produce increasingly sophisticated types of steel. In an age of global warming, that trio is not sustainable.

The three industrial giants Vattenfall (power), LKAB (mining) and SSAB (steel) have responded by developing technology to produce steel without coal. Their joint venture, launched in 2017, is called HYBRIT (Hydrogen Breakthrough Ironmaking Technology). Although only in its infancy, it has been shown to work, with vehicles made from fossil-free steel already delivered.

The problem is that the process requires huge volumes of electricity. But, based in the mountainous north, HYBRIT can count on ample hydropower. Access to clean energy has also drawn interest from other companies with green ambitions, like Northvolt, which uses lithium-ion technology to produce low-carbon batteries for electric vehicles. The combined impact has been a nascent green reindustrialization of the north.

However, these encouraging developments may be derailed as government action, driven by green climate change activism, has failed to meet the demand for a massive expansion of power generation. Meanwhile, six out of 12 nuclear reactors have been closed prematurely, to be replaced by wind power. Both trends have been in keeping with the green agenda, hailed as supposed progress.

The problem that activists have refused to acknowledge is that wind power production fluctuates. There is thus a limit to how much wind power may be installed, compared to sources like nuclear and hydro. The danger of sudden shortfalls of power is exacerbated by the fact that on very cold days, when demand spikes, there will normally be very little wind.

Activists are calling for the remaining nuclear power plants to be closed, and for a further expansion of wind power. But engineers warn that the share of wind power has already reached a level at which grid operators must plan for power shortages that will disconnect users – an outcome with seriously negative consequences for industry.

The problem is exacerbated by geography. To balance the hydropower stations in the north, nuclear power plants were built in the southern part of the country. As these are closed, insufficient high-voltage transmission capacity causes serious shortfalls of power. Green efforts to restore certain habitats further jeopardize smaller hydropower plants throughout the country.

The combined outcome of these causes is a greater need for burning imported fossil fuels – not only to meet growing power demand but to avoid destabilizing the national power grid.

Unrealistic expectations

Climate change activists typically ignore these effects, maintaining that political pressure from below is essential. Unless members of the young generation take to the streets to vent their anger, the thinking goes, they will be forced to accept a future marked by environmental calamities.

Looking back at the outcomes of efforts like the 1992 Kyoto Protocol and the 2015 Paris Agreement it is easy to understand their frustration. Further discouraging is that after a dip during the first year of the pandemic, carbon emissions for 2021 were estimated at only less than one percent below the record of 36.7 billion metric tons in 2019, and up by nearly five percent from 2020.

Emissions are going up rather than down because the big emitters are not on board. While some European governments are locked in fierce competition to devise the most ambitious goals on cutting emissions, others view the task with something like contempt. At last year’s Glasgow summit, India caused resentment by requesting that the phrase coal “phase out” be replaced by “phase down.”

Although the Biden administration raised the hopes of some by returning to the Paris Agreement, a win for Donald Trump in 2024 could lead the United States to again drop out. Meanwhile, Australia continues its coal mining activities, China is planning to build new power stations to burn dirty coal, and Russia plans massive investment in pipelines to pump natural gas. Activists protesting in European capitals are not going to change any of this.

One must then ask whether it is meaningful to keep talking about net-zero emissions by 2050 – aiming to keep global warming at 1.5 degrees – when most experts agree this is not going to happen. The list of factors that are moving too slowly, or even in the wrong direction, is simply too long.

Scenarios

By 2050, most of the current generation of political leaders will be out of power, and the environmentalists will have grown up. Accordingly, they will be able to cash in on the warm glow of today’s activism without having to face the consequences tomorrow. This is where the notion of a tipping point may come in, determining how climate politics and policy develop.

In one direction, democratic governments resign themselves to the fact that global warming will continue for some time, and start thinking about policies enabling long-term technological change aimed at a fossil-free future. There is much that can be done, ranging from fourth-generation nuclear power plants and the storage of surplus wind power to harnessing hydrogen and fusion.

In the other direction, governments succumb to the lure of environmentalist soundbites (“extinction rebellion”) that undermine the political process and encourage massive spending on ineffectual, short-term stunts. That impulse has driven powerful leaders to eagerly submit to lectures, and even insults, by young activists like Ms. Thunberg.

Political logic suggests that the latter is more likely. Science, however, still represents the only long-term solution, and discoveries cannot be sped up by street rallies. The implication is that sensationalism will continue to promote extreme measures that erode popular support for green causes and have minimal long-term impact.