A new leader in Colombia

Ivan Duque, Colombia’s newly elected president, takes office with a clear mandate from his supporters. He will likely try to slow the controversial peace accord reached with FARC guerrillas and address widespread public concerns.

In a nutshell

- Colombia’s new president, Ivan Duque, is a young conservative and opponent of the FARC peace agreement

- His supporters were unhappy with the accord and government failures on issues like crime and corruption

- Strong domestic and foreign investment, coupled with continued economic growth, should help Duque accomplish his priorities

On June 17, 2018, with 54 percent of the vote, Ivan Duque was elected president of Colombia. Labeled a young populist, Mr. Duque sees himself as part of a new generation that will shake up the country’s traditional politics. He aims to lead Colombia to an economic bonanza and reestablish its political and social order.

Much of Mr. Duque’s success was due to the backing of former President Alvaro Uribe Velez, now a senator. A considerable portion of the electorate, which supported Mr. Uribe and later Mr. Duque, was unhappy with the peace agreement reached with the guerrillas of the Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) and with the social unrest and organized crime affecting many rural parts of the country.

The saying in the campaign – “por el que diga Uribe” – was that these voters would support whomever Mr. Uribe picks, and his choice was Ivan Duque. A feature of the campaign was widespread discontent with the peace process, which gave five parliament seats to former FARC members and demobilized thousands of guerrilla fighters for reentry into society.

Campaign politics

Otherwise, public angst was focused on corruption, crime and violence, and the state’s failure to deal with these issues. This sense of insecurity exists even though Colombia’s homicide rate has been coming down for the past decade and is now at a 40-year low. This disparity between social angst and the actual crime rate is common to both Latin America and Europe.

Mr. Duque spent most of his campaign blaming these ills on the outgoing president, Juan Manuel Santos. The irony is that abroad, Mr. Santos enjoys an extremely favorable opinion. In addition to the peace accord that ended half a century of conflict with the FARC, his presidency oversaw a booming economy and a near tripling of gross domestic product (GDP), from $98 billion to $286 billion.

Crime also declined considerably, with a 2017 homicide rate of 24.8 per 100,000 residents. That was the country’s lowest level in decades, after a peak of 78 in 1991, and less than half the rate of just 15 years ago. To Mr. Santos’ credit, increased government spending on social issues also helped bring poverty down significantly. The GINI coefficient, a common index of inequality, declined by nearly 10 percent under his watch, and the poverty level declined from 30 to 17 percent.

A sense of insecurity exists even though Colombia’s homicide rate is now at a 40-year low.

In the clearest sign of international confidence in his government, foreign investment soared during his tenure. Mr. Santos became a prominent figure regionally and beyond, giving Colombia more clout in the global community. Just before leaving office, he certified Colombia as the 37th member of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It is no coincidence that the greatest policy efforts of the Santos administration mirrored the group’s recommendations for Colombia’s membership application.

President Duque’s victory, in addition to recognizing Mr. Uribe’s influence in the country’s politics, marked a continuation of conservative rule. Mr. Santos was himself a minister under President Uribe (2002-2010). In 2010, he won the presidency with the support of the conservatives in Mr. Uribe’s party and the two traditional parties (Liberal and Conservative) that had governed Colombia for the half-century prior to the 2002 elections.

The Santos victory also marked a growing rift with the urban electorate, which was overwhelmingly left of center and in the latest election supported Gustavo Petro, the former mayor of Bogota and a former guerrilla. Mr. Petro won 24 percent of the vote in the first round, barely edging out former Medellin mayor Sergio Fajardo. In the second round against Mr. Duque, Gustavo Petro could only muster 41 percent of the vote.

Rural issues

In addition to corruption and security, the electorate has made clear its concerns about the state’s failure over basic social issues like education and the welfare of rural residents. Organized crime, in the form of the gangs known in Spanish as BACRIM, make life in the countryside much more dangerous than in Colombia’s cities. A weak state has been unable to carry out the terms of the peace accord with the FARC, leaving several million Colombians displaced, pushed off their lands and waiting impatiently for special courts to deal with their restitution claims.

Similarly, the government has been unable to meet its obligations under the peace agreement. It has failed to resettle disarmed guerrilla fighters and to protect farmers and small landholders from the National Liberation Army (ELN), the remaining guerrilla group which has not signed a peace treaty. The government has also failed miserably to keep the BACRIM from running roughshod over the countryside, especially in the north and southwest, where the FARC had been in control for years.

Facts & figures

Criminal actors and economies in Colombia, 2017

To make matters worse, over the two years since the process began, dozens of social activists have been murdered, including labor leaders, heads of rural cooperatives and journalists. The culprits are likely the BACRIM and assassins hired by local landowners, who were formerly behind the marauding paramilitaries created to fight guerrillas in place of the incapable state. The state does not appear any better at guaranteeing the rule of law in the countryside than it was 10 or 20 years ago.

It will not be easy for President Duque to fulfill his promises to change the peace accord and reduce rural crime. He has promised to reopen negotiations with FARC leaders and impose heavier penalties on former guerrilla leaders, but that may be the easy part.

It will be harder to speed up the pace at which the so-called Transitional Justice System (JEP) carries out its proceedings. To complicate matters, Mr. Uribe himself has been accused of suborning witnesses in cases against paramilitary criminals. His brother, Santiago Uribe, is in jail, awaiting sentencing for his involvement with paramilitary death squads.

The “Uribistas” who want swift and severe penalties for ex-guerrillas do not want the justice system to condemn anyone on their side of the long struggle. Large landowners like the Uribe brothers can defend themselves, often in illegal or improper ways. But small landholders are powerless from the BACRIM without a strong state.

Land rights will also continue to be an important and complicated issue. There is, in effect, a standoff between large landowners and victims of the armed conflict, whose claims to more than 7 million hectares of land – while recognized under the law – are stuck in a juridical and bureaucratic traffic jam. More than 60 percent of the claimants have not even been able to begin the restitution process.

New agenda

The conservative government wants to reduce social spending, create investment incentives in the private sector, and continue to attract foreign investment in growth sectors like energy and infrastructure. While the new president has acknowledged the need for reforms in the rural sector, where most of the guerrilla fighting took place and where most of the displaced people are now waiting for land, he has not indicated how more rural spending will fit into his smaller-government agenda. Recent private sector studies have suggested that paying for the peace process and rural reform could cost as much as 5 percent of the nation’s GDP.

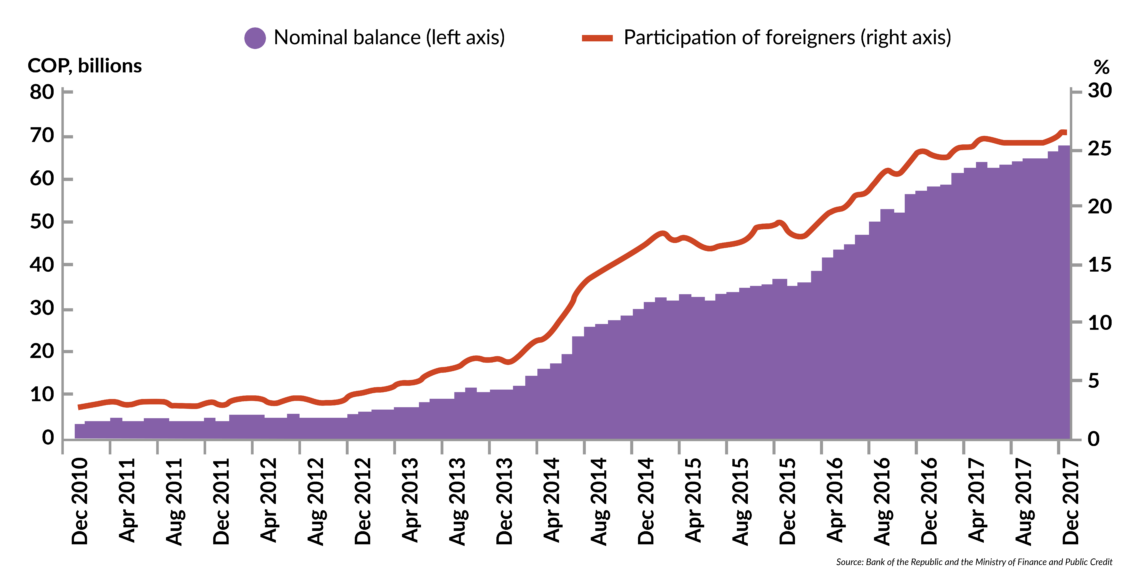

Facts & figures

Foreign investment in Treasury notes

Most immediately, President Duque will have to deal with the huge influx of migrants from Venezuela. They number more than half a million in 2018, close to a million over the past three years, and hundreds of thousands remain huddled in makeshift camps near Colombia’s eastern border. Emigration from Venezuela to other neighboring countries such as Brazil, Ecuador and Peru, has created a regional crisis that Mr. Duque must help manage.

Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro has blamed Bogota for the border crisis and has threatened military reprisals. Border violence will not help the new government fulfill its policy agenda, and rumors that the Trump administration is considering arming the Venezuelan opposition only make matters worse.

Mr. Duque has a full plate of problems to deal with. The cultivation of coca has increased over the past two years, affecting not only law and order in Colombia but greatly displeasing the United States. For 20 years, under “Plan Colombia,” the American government has been pouring money into Colombia to curb the flow of cocaine into the U.S. Most of that money went to support the military’s effort to contain insurgents and reduce drug cultivation through aerial fumigation.

As part of the peace process, then-President Santos asked the U.S. to change the name of the program to “Peace Colombia” and to continue providing funds for rural reform, drug rehabilitation and other social programs. In response, U.S. President Donald Trump threatened to decertify Colombia as a cooperating ally in the war on drugs and demanded that it pay for its own anti-drug programs.

Recent studies have indicated that coca is being cultivated in very poor areas, suggesting that crop substitution programs are more successful than the earlier fumigation efforts. Whatever his preferences, President Duque will have to deal with this issue sooner rather than later – President Trump plans to visit Colombia before the end of the year.

Getting tough with the FARC will be complicated by the fact that the other guerrilla group, the ELN, has increased its activities over the past year. The group has taken advantage of thousands of demobilized former FARC fighters and of the power vacuum created by the FARC’s withdrawal from large parts of territory in which they had been the only source of authority for decades. If Mr. Duque wants peace in the countryside, he will have to deal with the ELN.

Congressional jockeying

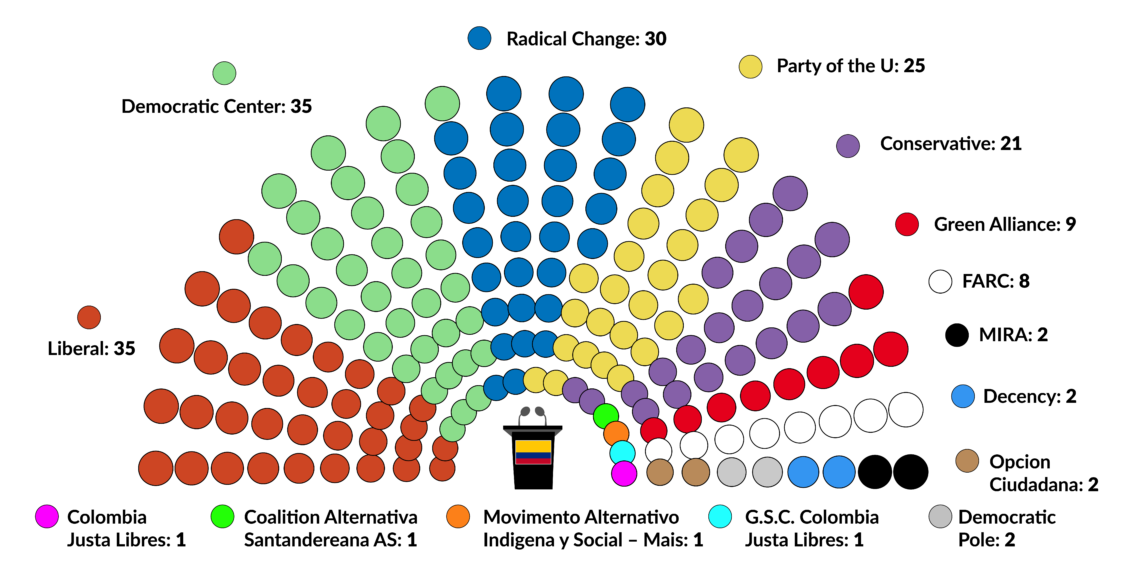

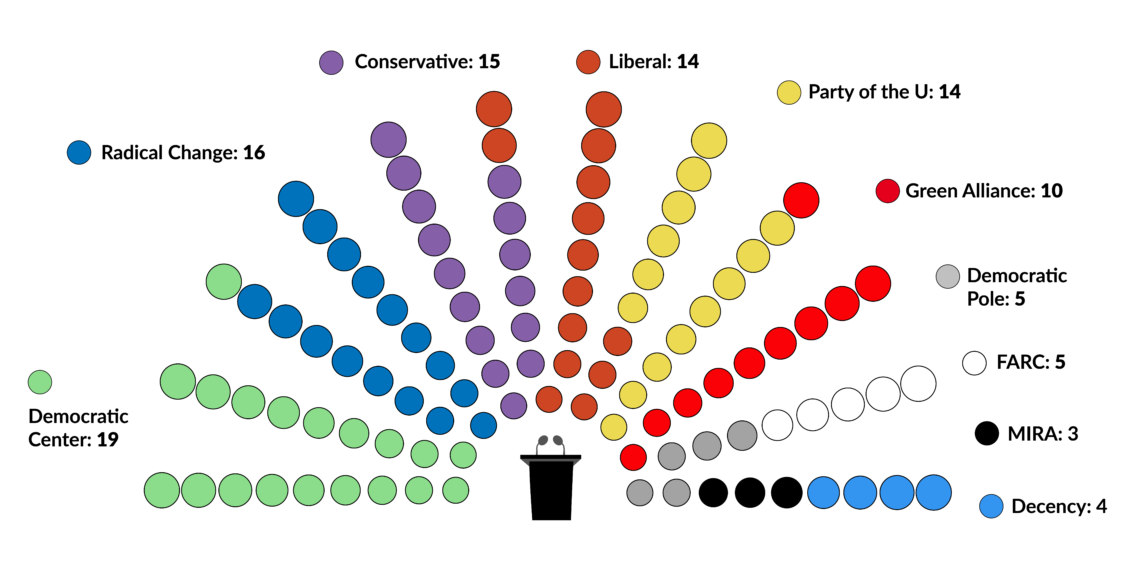

In congress, the political situation remains fluid. Mr. Duque forged an electoral alliance between his own party (the Democratic Center), the traditional conservative parties, Mr. Uribe’s party (the Party of the U) and the Radical Change party. Since the election, Mr. Duque has been negotiating with these groups to create a bloc that will deal with his legislative agenda. Right now, the situation remains flexible, with one party or another announcing they will or will not cooperate depending on what the president offers.

Facts & figures

Composition of the House of Representatives of Colombia

The man he beat out for the conservative nomination, German Vargas, has become a significant player. If all of these conservative parties vote together, they will have a majority in both chambers. At this point, all that can be said is that to the extent that President Duque wins support from the traditional groups (Liberals, Conservatives and Radical Change), he will reduce Mr. Uribe’s influence. While that will help him in the short run, it suggests that these regional and local barons will increase the power of clientelism and patronage politics and reduce the capacity of the central state.

On the other side of the aisle, Gustavo Petro, who came so close to the presidency, has since seen his influence fade. That has been the case mainly because his personal party created for the campaign, the Progressive Movement (sometimes referred to as Decency), has failed to win official recognition from the National Electoral Council. That means they cannot participate in regional and local elections in the coming year. His party will have only six seats in the new congress and will have to work with the Greens (19 seats in the two chambers), the Alternative Democratic Pole (seven), the FARC representatives (five) and several other fragments, each with one or two seats.

A referendum was held two weeks after Mr. Duque was inaugurated, which mobilized a huge public turnout in favor of an anti-corruption project. Over 90 percent of voters were in favor of the project, confirming recent polling data, but it failed to achieve official recognition because the turnout was a million votes short of the constitutional minimum required.

Even so, the result suggests that urban or progressive forces can express their interests in a variety of ways under the conservative government. Also of note was the meeting Mr. Duque hosted in the presidential palace to celebrate the vote, a meeting which included the five FARC members of congress. That demonstrated his independence from Mr. Uribe, who opposed having the former guerrillas in the palace.

Scenarios

The most likely scenario, at least for the administration’s first year, is an effort by the government and the coalition’s Uribe faction to slow or stop the peace process as much as possible. A recent poll indicated that 60 percent of the population wanted to continue peace talks with the ELN and continue to work with the FARC to carry out the peace accords. In fact, the government’s first announcements of its “demands” on the FARC (from August 27) suggest that the government will not ask anything too extreme. While the situation in the countryside will continue to fester, the conservative coalition will do little or nothing to correct it.

The government can get away with an obstructionist strategy because domestic and foreign investors will provide a boost to the economy. As the economic expansion continues, the government will have more revenue to carry out whatever social programs it prioritizes – likely meaning education, healthcare access, middle-income housing, and land restitution. The last is the most controversial, and whatever support Mr. Duque gives to the program, it is unlikely to relieve the desperate situation of the millions of displaced people.

The less likely scenario is an alliance between President Duque and the traditional conservative parties. They would join forces to reduce Alvaro Uribe’s influence over policy and return power to the regional clientelist barons.

That kind of alliance would favor peace talks with the ELN in order to improve the security situation in the countryside, and would mean a greater effort to reduce the BACRIM’s power. They would also deal with urban-based elites and attempt to compromise on social programs beneficial for cities. Such a scenario would provide greater stability for the country than cooperation between the Duque and Uribe factions, but it is an unlikely one.