Scenarios for Chad’s President Idriss Deby

Chad’s President Idriss Deby leads an authoritarian government that is increasingly under pressure, both politically and economically. However, his regime has been a strong ally of the West. A new constitution that strengthened his grip on power was approved this year, but it could, ironically, further undermine his legitimacy.

In a nutshell

- Chadian President Idriss Deby used a new constitution to consolidate his power

- Under his rule, Chad has been a strong, stable partner of the West

- Repression and economic underperformance are putting a dent in his legitimacy

- More political instability and economic difficulties are likely to occur

In power since 1990, Chadian President Idriss Deby has just strengthened his rule by enacting a new constitution that will keep him in office for decades. Recently, however, political and economic developments are putting his regime’s legitimacy to the test. At the same time, Chad remains a strong military power in a volatile and conflict-ridden region, with fragile states and vast ungoverned areas.

Resilient rule

President Deby has survived two coup attempts (in 2006 and 2008) and has won five presidential elections (in 1996, 2001, 2006, 2011 and 2016), despite suspected irregularities and successive opposition boycotts. In 2006, he removed term limits in an amendment to the country’s constitution. His resilience in office can be explained by a combination of three factors: ethnic imbalances, regional dynamics and military power.

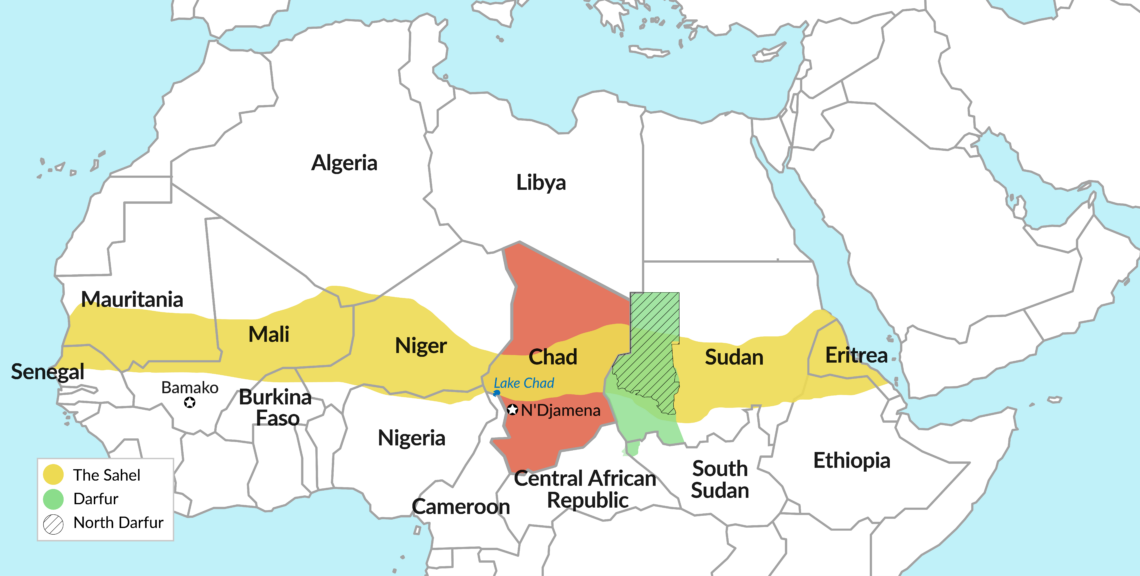

Mr. Deby is a Zaghawa, a Muslim ethnic group that is mainly concentrated in eastern Chad and in the Sudanese state of North Darfur. In Darfur, the Zaghawa played a leading role in the insurrection against Sudan’s central government. When the conflict started in 2001, President Deby chose not to support the Zaghawa. However, it soon became clear that to remain in power, he needed to secure their loyalty and even antagonize the regime in Khartoum, which had backed his coup against Hissene Habre in 1990. Although a demographic minority in Chad, the Zaghawa have formed the backbone of the country’s military, political and economic elite since the 1990s.

Chad has stood out as a reliable Western ally in a region marked by state weakness and volatility.

In the early 2010s, the security and political balance in the Sahel was dramatically altered. The militant Islamist group Boko Haram became increasingly active, launching attacks in Nigeria, Cameroon, Niger and Chad. After the fall of Muammar Qaddafi in 2011, a rebellion by the Tuareg people in northern Mali led to a coup in Bamako and the ouster of President Amadou Toumani Toure. In 2013, another coup removed President Francois Bozize in the Central African Republic and put the country on the verge of genocide.

While these security challenges mainly affected the Sahel countries, they would also be felt in Europe and the United States, putting issues like terrorism and migration at the top of their agendas.

Within this context, Chad stood out as an invaluable and reliable Western ally in a region marked by state weakness and volatility. For France, Chad has always been a central piece of the “Francafrique” puzzle, providing a strategic base for its military on the continent. For the U.S., it has been a key ally in the war against terrorism in critical places like Mali, Nigeria and Niger.

Under President Deby’s rule, the country became a leader in the fight against terrorism in places like Nigeria, Mali and the Lake Chad region. Chad also played a key role in the removal of Central African Republic President Francois Bozize in 2013. In 2015, Chadian forces made a critical contribution in the regional offensive against Boko Haram. That same year, the Multinational Joint Task Force (made up of troops from Benin, Cameroon, Chad, Niger and Nigeria and mandated to fight Boko Haram) moved its headquarters to N’Djamena. Chad plays a vital role in the unstable, resource-rich Lake Chad Basin, where the borders of Chad, Niger, Nigeria and Cameroon meet. Criminal and terrorist groups, including Boko Haram, recruit heavily from this area. It is also a crossing point for many migrants.

Facts & figures

Chad: a key player in the Sahel

Supporting Chad’s prominent role in regional security is a well-equipped army of about 30,000 troops, with robust experience in desert warfare. According to World Bank data, between 2005 and 2009, Chad’s military expenditure as a share of gross domestic product (GDP) increased almost tenfold, from 0.84 percent to 7.9 percent. As the country benefited from the 2000s commodities super cycle, President Deby decided to invest oil money in the army, serving a double purpose: to strengthen Chad’s position as a regional stabilizing force, and to crush dissidents at home.

Political crisis

Chad is a centralized, authoritarian state, with little democratic tradition and a fragmented political opposition (there are about 200 registered parties). However, President Deby is increasingly coming up against stronger competition. Following the 2016 elections, which the opposition described as “an electoral coup,” a coalition of 29 opposition parties and six presidential candidates formed the New Opposition Front for Change (FONAC).

In March 2018, President Deby convened a national forum for institutional reforms to “lay the foundations of Chad’s fourth republic.” The forum, which was boycotted by the opposition, recommended that the president be limited to two six-year terms (previously, the president could serve for an unlimited number of five-year terms) and that the post of prime minister be abolished. Two months later, after approval by the country’s parliament, Chad’s new constitution, including the recommended changes, came into force. The parties comprising FONAC boycotted the voting. According to the new constitution, President Deby can stay in power until 2033, as the term limit only becomes effective starting with the 2021 presidential election.

While recent events make it possible for President Deby to remain in power in the long run, his regime is in a precarious position. The political opposition is now joined by ordinary citizens – civil servants, students, taxi drivers and street vendors – who are suffering from the effects of the government’s disappointing economic performance.

Economic crisis

The drop in oil prices in 2014 plunged the country into a deep economic crisis (oil accounted for 70 percent of state revenue). The government became unable to meet its obligations, both internal and external. In 2017, the budget deficit exceeded $400 million, while the government failed to pay some salaries. This led to several strikes, including one in early 2018 that lasted seven weeks and resulted in the closure of schools, hospitals and courts. Although an agreement was reached between the government and trade unions, increasing social and economic upheaval is expected ahead of the November 2018 parliamentary elections.

Chad’s prospects for economic growth remain weak.

However, the government has notched up two important victories. At a September 2017 conference, donors exceeded the regime’s expectations and pledged $20 billion to fund the country’s 2017-21 National Development Plan. And in April 2018, the International Monetary Fund resumed loan disbursements to Chad, after the government reached an agreement with Anglo-Swiss natural resource company Glencore on the restructuring of an oil-backed loan of more than $1 billion.

Still, prospects for economic growth and recovery remain weak. Chad is a landlocked, low-income country with scarce resources. It is ranked 180 out of 190 countries in the World Bank’s Doing Business ranking, and 162 out of 170 in the Heritage Foundation’s Index of Economic Freedom. Chad’s small, underdeveloped private sector stands in sharp contrast to its large informal sector and bloated, largely inefficient state apparatus (salaries in the public sector cost the state an estimated $50 million per month, in a country where the minimum wage is $120 per month).

The potential increase in global oil prices could be good news for the Chadian economy. Global economic growth is boosting demand. Meanwhile, supply is shrinking due to cuts in Venezuelan, Russian and Saudi production, as well as U.S. President Donald Trump’s decision to reimplement sanctions on Iran. Analysts say next year oil prices could reach $100 a barrel. Under this scenario, Chad could benefit as an alternative oil supplier.

However, Chad’s economic prospects would likely remain fragile for three reasons. First, Chadian oil is low quality. Second, the agreement with Glencore means that a significant part of the country’s oil production will have to be allocated to the repayment of its debt. Third, the Chadian regime is expected to repeat the strategy adopted during the 2000s commodities boom, that is, abstain from major – and painful – reforms and trust oil management to the president’s inner circle.

Scenarios

The new constitution helps President Deby strengthen his grip on power. However, with state repression increasing and the economic crisis deepening, the regime’s legitimacy is being strongly contested on both the political and economic fronts. Taking all this into consideration, we can envision three different scenarios.

Business as usual

Under the first scenario, which remains the most likely in the short to medium term, President Deby will continue to rule Chad, supported by the Zaghawa elite and by the country’s security forces. The changes enacted by the new constitution will impose both economic and political costs. President Deby has replaced the rule of law by the rule of man. The arbitrariness and unpredictability that characterized recent changes will tend to scare off potential investors.

With the regime’s legitimacy compromised by President Deby’s political ambitions and poor economic performance, levels of state repression are expected to remain high. If the regime does not undertake meaningful reforms oriented toward a gradual political opening and economic development, the next decade will be lost for Chad.

Political change

A second, less likely, scenario would see political change over the next several years. The legislative elections, expected to take place in November 2018, will be a critical moment for President Deby and could ignite underlying tensions within Chad’s ruling elite. In this case, a “Zimbabwean style” coup could take place. Many among the Zaghawa elite do not trust Mr. Deby’s powerful network of relatives, particularly his sons and first lady Hinda Deby Itno, who has managed to secure great influence in the country.

Although the Chadian army was ethnically designed to serve the Deby regime, its cohesiveness and loyalty to the president are questionable, especially among the more poorly paid units. In case some portions of the army and the Zaghawa elite – the very institutions upon which the Chadian regime rests – agree that it is time for Mr. Deby to leave power, then a top-down process of political change would become a possibility.

If President Deby were overthrown, it could unleash political chaos. Domestic strife could potentially even lead to armed conflict and prolonged instability, with catastrophi

Authoritarian development

Under a third scenario, Chad’s fourth republic would give way to a model of authoritarian development. Although remote, the likelihood of such a scenario could increase if oil prices rise and remain high. Western donors and allies would turn a blind eye to President Deby’s methods of rule, but in return, they would demand a stronger commitment to sound economic policies.

Chad would keep its role as the West’s reliable ally in the Sahel. While maintaining his external leverage, Deby’s regime could regain some internal legitimacy by reducing corruption and implementing growth- and development-oriented policie