The systems that support corruption in Africa

Despite increasing international regulations, corrupt leaders in Africa continue to find ways to enrich themselves using illicit means. Globalization, ill-conceived aid programs and increasing grip on power pandemic are factors that have allowed for the graft to go on.

In a nutshell

- Globalization has helped corrupt officials hide money

- Authoritarianism makes graft attractive and easy

- Aid programs supply funds that corrupt leaders embezzle

For the last 50 years of the 20th century, authoritarian nationalism within a bipolar world order characterized most African countries’ politics. At the time, the global superpowers were willing to support and aid authoritarian leaders. Demands for accountability were few to nonexistent. The continent’s “big men” were able to amass colossal personal riches.

One of the most legendary fortunes was that of Mobutu Sese Seko, who led Zaire from 1967 to 1997. Mobutu’s rule was a product of the Cold War. Seen as a bulwark against Soviet influence, he was supported by the United States. According to documents from the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund, between 1970 and 1994, Zaire received some $8.5 billion in grants and loans. According to some reports, the CIA disbursed over $20 million in cash there.

As president, Mobutu controlled the country’s vast resources. In 1978, for example, mining firm Gecamines deposited its earnings directly into a presidential account. Such practices allowed Mobutu to establish an official presidential budget of $400 million per year. He employed a 10,000-strong presidential guard and built a vast patronage network. Mobutu was deposed in 1997, with an impressive personal fortune estimated at between $1 billion and $5 billion. In 1986, after Switzerland’s unprecedented decision to freeze the accounts of Philippine President Ferdinand Marcos, Mobutu channeled his money to accounts all over the world, from China to South America.

Throughout the Cold War, corrupt leaders in resource-rich and strategically relevant countries received their money from governments and companies. In a world where corruption was not at the top of the agenda and there was little regulation, some of the money was spent to sustain patronage networks, build luxurious palaces and hold elaborate ceremonies. The rest was placed in safe havens overseas, in bank accounts and properties.

During the Cold War, corrupt leaders got money from governments and companies.

Three factors have contributed to the persistence of corruption in the post-Cold War period. The first is globalization, with its multiplication and acceleration of financial flows. The second is continual rent-seeking, involving political elites and foreign companies. The third is the consolidation of what Zambian economist Dambisa Moyo describes as “systemic aid.”

Moving the money

The end of the Cold War, the subsequent waves of democratization and the acceleration of globalization changed the corruption dynamic. Geopolitical interests, while still important, became less prominent. Public scrutiny and the increased availability of information required corrupt leaders to find more sophisticated ways to accumulate and hide illicit money. Increasing anti-corruption regulations have made life more difficult for kleptocrats throughout the world.

Plenty of prominent figures have already been caught with their hands in the cookie jar. In South Africa, high-profile politicians and leaders were arrested for their corrupt involvement in state capture. In the Democratic Republic of the Congo, the “Lumumba Papers” revealed that in 2016 large sums of money were transferred to the country’s national election commission. Moreover, the president’s former chief of staff was convicted of embezzling more than $48 million. In Angola, a former transport minister was sentenced to 14 years in prison for corruption and embezzlement of state funds. In Malawi, banker Thomson Mpinganjira was arrested for allegedly attempting to bribe judges.

Facts & figures

To avoid being caught, corrupt officials channel their fortunes into the international financial system. In Africa’s case, the money often goes to countries with former colonial ties or to family members.

None of this would be possible, however, without the support of legal firms, banks, real estate professionals and public relations companies. In 2016, an investigator for Global Witness, an organization dedicated to fighting corruption worldwide, revealed that 12 of the 13 law firms he had approached were open to discussing moving illicit money from Africa to the U.S.

Moreover, many of the most upscale real estate properties in places like London and Manhattan were acquired through shell companies. According to a 2017 investigation by the New York Times, more than half of the $8 billion worth of annual transactions in New York real estate involved such firms. Given today’s rapid dissemination of information, reputation protection has also become more important. Therefore, PR firms have gained a key role in whitewashing corrupt practices, as seen in the Gupta Scandal in South Africa.

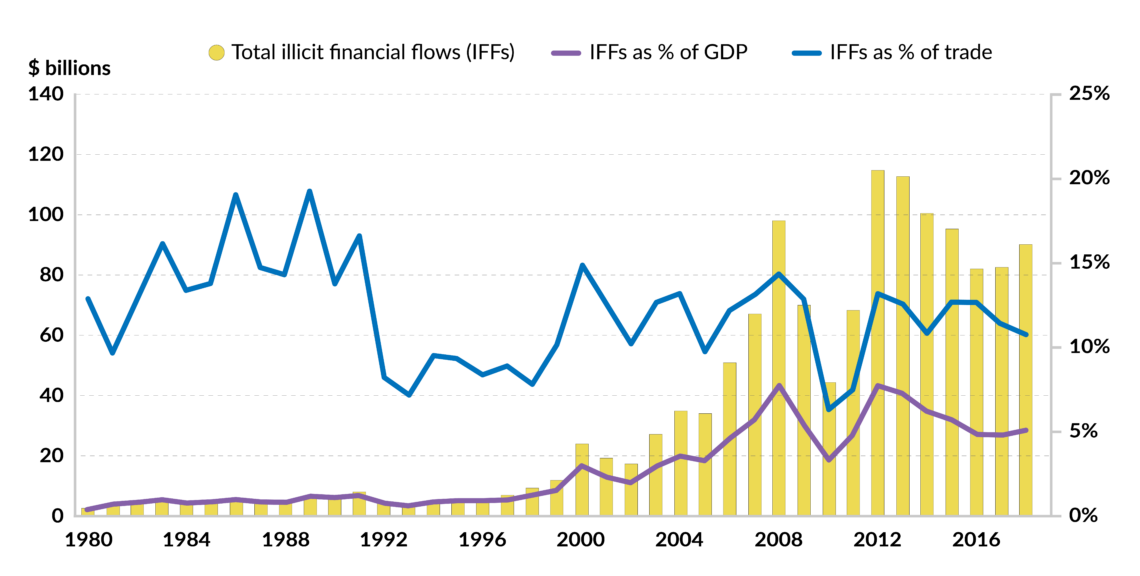

A recent report by the Brookings Institution estimated that between 1980 and 2018, foreign direct investment and official development assistance to sub-Saharan Africa reached nearly $2 trillion, whereas illicit financial flows from the region reached $1 trillion. Those illicit flows sharply increased in the early 2000s. South Africa, the DRC, Nigeria and Ethiopia were the top sources of outgoing money. The rapid rise coincided with a global commodities boom and was accompanied by a shift in destinations for the money, with the East Asia and Pacific regions assuming a more prominent role.

Despite efforts to increase transparency and regulation, financiers could rapidly circulate illicit money around the world, thanks to a vast network of transnational actors. They have used vehicles such as offshore accounts, shell companies and family offices to circumvent regulations and conceal the money’s origins and beneficiaries. According to research by Oxfam, some 30 percent of Africa’s wealth may have been moved offshore.

Corruption-authoritarianism link

Rent-seeking and corruption have become pervasive in some African countries due to historical, economic and cultural factors. These include weak property rights, incipient civil societies and a lack of incentives for private enterprise and investment. Because the state often has a monopoly on political and economic power, capturing the state and its resources becomes the only game in town.

Money from extraction can fund militias, bribe key decision makers or buy votes.

Corrupt leaders in Africa have used their control of political and economic institutions to enrich themselves and perpetuate their power. This trend is particularly visible in countries where politicians and military officials control access to valuable natural resources, generating perverse incentives and a vicious cycle. The money from extraction can be distributed to fund militias, bribe key decision makers or buy votes.

Not surprisingly, long-ruling leaders like President Paul Biya of Cameroon, President Teodoro Obiang of Equatorial Guinea or President Ali Bongo of Gabon have amassed vast personal fortunes.

Take Cameroon, where Paul Biya has been president since 1982. The country is rich in oil and minerals. However, between 1977 and 2006, more than 50 percent of the country’s oil revenues did not make it into the federal budget. In a 2018 report, the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP) claimed that President Biya had spent at least 1,645 days on private visits abroad since coming to power. Despite widespread poverty, Boko Haram attacks and a separatist conflict, the president won another seven-year mandate in 2018 thanks to a firmly established system of coercion and appropriation.

However, as the case of South Africa shows, corruption can also be endemic in democratic countries with economies that are relatively developed compared to the rest of the continent. The scandal that led to the fall of President Jacob Zuma exposed a process of state capture involving key ministries, companies, public agencies, the prosecution authority, and the police. By exerting control over key institutions, a political and economic elite could embezzle illicit funds while securing political power.

Aid’s collateral damage

Donors and aid agencies often unintentionally represent the supply side of corruption. Aid can assume several forms, from bilateral and multilateral aid to humanitarian relief, technical assistance programs or debt pardoning. Annually, the volume of humanitarian assistance alone is estimated at $171.3 billion.

Whether that assistance is effective remains a contentious issue, with some researchers pointing out that aid dependency causes economic inefficiencies, harms industrialization, fosters corruption and slows growth. The funds are misappropriated by providers, contractors and political officials who pay kickbacks, inflate salaries or overcharge for goods and services.

A recent study published by the World Bank found a positive correlation between its own payouts to the most aid-dependent countries and increases in deposits in offshore financial centers that originate from those countries. The leakage rate, according to the study, is about 7.5 percent. Given the absence of external and independent regulation, multilateral aid from international organizations tends to be more vulnerable to corruption than bilateral aid.

The pandemic will strengthen state power in Africa.

For example, in the early 2000s, contractors and officials misapplied 90 percent of the $100 million in funding for a refugee resettlement project in East Africa. In Uganda, in 2005, the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria suspended nearly $370 million worth of grants after evidence of theft and mismanagement. In Malawi, in 2013, a loophole in the computer-based financial information storage system was exploited by government officials who diverted up to $250 million to private companies in exchange for fictional services.

During the 2014-2016 Ebola epidemic, the Red Cross lost $5 million to fraud in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea. In the DRC, a recently discovered scam saw aid workers, chiefs and local officials colluding to siphon off money in an emergency aid program. In another case, refugees from five African countries have accused UNHCR employees and local officers of demanding bribes in exchange for access to food, medical referrals and resettlement.

More recently, in South Africa – where the government secured a $4.3 billion loan from the International Monetary Fund to ameliorate the effects of the Covid-19 pandemic – several scandals came to light involving the misuse and diversion of funds. Abuses ranged from fraud schemes in the purchase of personal protective equipment to patronage-based politicization of food distribution.

Scenarios

Four trends will determine the future of corruption in Africa. First is the advancement of anti-corruption mechanisms. Second are changing public attitudes and the appearance of anti-corruption movements. Third is the evolution of state power. The final trend is the extent to which the Covid-19 pandemic affects capital inflows to Africa.

Under the most likely scenario, political corruption will slightly decrease in the medium term. Like in other regions, the pandemic will strengthen state power in Africa. Yet while centralized power favors corruption, two trends will push in the opposite direction. One is the development of ever-more sophisticated anti-corruption mechanisms, asset recovery efforts and stricter regulation. The other is African citizens’ increasingly vocal opposition to corrupt practices.

Moreover, aid flows could shrink due to economic uncertainty, political polarization and agencies’ fear of besmirching their reputation. Cooperation with Africa will focus on a more business-oriented approach based on mobilizing private-sector investment. The United Kingdom, the European Union and the U.S. have promoted such strategies, which could help decrease mid-level corruption.

Under a second, slightly less likely scenario, political corruption will remain pervasive in the long term. Political leaders would adapt to new circumstances by depending less on coercion and more on bribery. Though increasing regulation may still deter some graft, the aid industry would remain vulnerable to corruption due to the absence of independent regulators and disparate accountability mechanisms.