Corruption in Africa: trends and scenarios

Sub-Saharan Africa has, according to some measures, the highest corruption levels. Although some countries have made great strides in fighting graft, others remain mired in corrupt systems. Democratic institutions are an important factor, but so is economic freedom.

In a nutshell

- Corruption is rife throughout Africa, though some countries are improving

- As graft becomes more visible, Africans will increasingly demand better

- Authoritarian regimes will use anti-corruption movements to quash the opposition

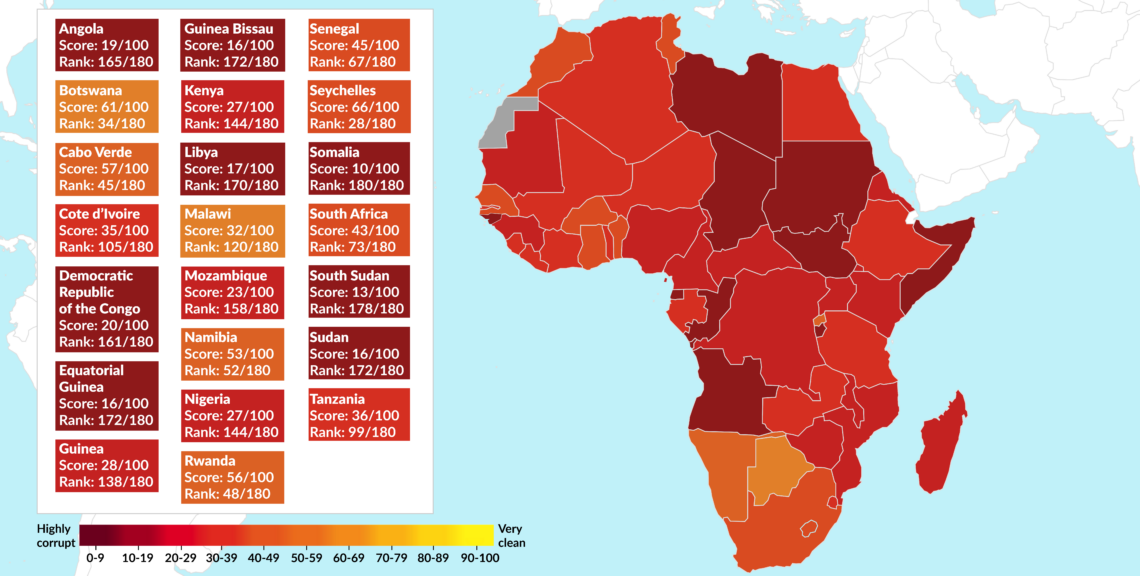

According to Transparency International’s 2018 Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI), sub-Saharan Africa remains the world’s most corrupt region. The picture is not homogeneous, however: while corruption continues to hamper growth in some big African economies, like Nigeria, South Africa and Kenya, countries like Botswana, Seychelles, Cabo Verde, Rwanda and Namibia perform better than OECD countries such as Italy or Greece.

The high incidence of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa is the result of a combination of historical, political and economic factors. After independence, corruption was widely tolerated both within and outside Africa, as a necessary growing pain. The first postindependence generation of leaders used their participation in liberation movements to legitimize their hold on power, while corruption, patronage and rent-seeking became commonplace. The phenomenon is reflected in the fortunes amassed by Mobutu Sese Seko of Zaire (1965-1997), Daniel arap Moi of Kenya (1978-2002), Hastings Banda of Malawi (1966-1994) and Muammar Qaddafi of Libya (1969-2011).

Furthermore, most of these countries did not have a significant – let alone independent – private sector. That situation was made worse by the adoption of socialist policies in several states. Likewise, civil society in many countries was often co-opted or dependent on foreign aid.

In some countries, large-scale corruption coexists with a functioning state and a formally democratic regime.

Financial opacity and abundant natural resources also drive corruption. According to a 2015 report by the High Level Panel on Illicit Financial Flows from Africa, an estimated $50 billion illicitly flows out of Africa each year as a result of illegitimate commercial transactions, tax evasion, criminal activities, corruption, bribery and abuse of office. The situation in Africa suggests a positive correlation between natural resources and corruption: rent-seeking behavior is prevalent in resource-rich countries like the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Nigeria and Sudan.

State capture and hidden debts

In some countries, large-scale corruption coexists with a functioning state and a formally democratic regime. In Mozambique, for example, a hidden debt scandal is having a profound impact on the country’s fragile economy. The debt dates back to 2013 and 2014, when high ranking political and military figures secretively negotiated a series of loans estimated to be worth $2.2 billion. Three factors amplify the impact of this case. First, the size of the debt, which corresponds to more than 15 percent of Mozambique’s gross domestic product (GDP). Second, the case is being investigated by the FBI, it involves at least four international banks and has consequences for bondholders in several countries. Finally, the practical implications – insolvency and credit suspension – have raised a fierce debate over the legality of this debt, since the loan was neither discussed nor approved by parliament.

Another notable case was the process of state capture during Jacob Zuma’s presidency (2009-2018). This case is relevant because South Africa is among the continent’s most consolidated democracies. While this did not prevent high-level, systemic corruption within the ruling African National Congress party, the corruption was denounced and exposed by the opposition and civil society organizations and brought to court. The separation of powers, as well as political and civil liberties, played a decisive role in exposing and dealing with the corruption, if not containing and sanctioning it.

‘Improvers’

Two African countries – Senegal and Cote d’Ivoire – are among the 20 “improvers” singled out by the 2018 CPI. According to the African Development Bank’s 2019 African Economic Outlook, these countries are also expected to be among the continent’s fastest-growing economies in 2019 (with growth rates of 7 and 7.4 percent respectively). In both cases, growth has been driven by political stability, macroeconomic reforms and business-friendly policies.

Facts & figures

Democratic performance

2018 Ibrahim Index of African Governance: Human Rights & Participation ranking

In the CPI, Senegal improved from 36 points in 2012 to 45 points in 2018 – two points above the global average. This achievement reflects a combination of political will (under President Macky Sall’s leadership), strong institutions (including a court to specifically address cases of illicit enrichment, as well as a National Office against Fraud and Corruption) and sound legislation (such as the 2014 asset declaration law).

Cote d’Ivoire, which went from 22 points in 2011 to 35 in 2018, shows a similar trajectory. President Alassane Ouattara, an admirer of the Rwandan model, ordered the creation of new anti-corruption bodies, including the Brigade for the Fight Against Corruption, a High Authority for Good Governance and an Anti-Racketeering Unit. The parliament passed an anti-corruption law in 2014, while mechanisms were established for citizens to report bribery and media campaigns were used to raise awareness. These measures have been reinforced by the effective investigation and persecution of high-level officials.

Wait and see: Nigeria and Angola

During Nigerian President Muhammadu Buhari’s first term, some important steps were taken. They include the creation of a presidential advisory committee against corruption, the Treasury Single Account initiative (to consolidate all government agency income in a single account at the Central Bank of Nigeria), improvements in public procurement and asset declaration, and the implementation of a national anti-corruption strategy. The results have been mixed. Several high-profile politicians have been prosecuted and the country has recovered a significant amount of stolen funds. However, those targeted are mostly from the opposition People’s Democratic Party, while the repatriation of funds has been marked by controversies, including the decision – ahead of the presidential elections – to redistribute the money to around 302,000 households in 19 states.

In Angola, President Joao Lourenco has also taken concrete measures against corruption. While the country still ranks 165 out of 180 countries according to the CPI index, Angola managed to gain four points since 2015. Since Mr. Lourenco came to power, more than 250 politicians, ambassadors, public managers and high-ranking members of the military have been investigated, and several other high-profile figures prosecuted. The list includes Isabel dos Santos, who was removed as chief executive of the huge oil firm Sonangol, Jose Filomeno dos Santos, the former CEO of the Angolan Sovereign Fund, as well as prominent figures within the People’s Movement for the Liberation of Angola (MPLA) party, such as a former transport minister and the ruling party’s former spokesman. Contrary to what is happening in Tanzania, where President John Magufuli’s personal anti-corruption crusade is deterring investors, in Angola, anti-corruption efforts are in line with President Lourenco’s economic strategy, aiming at diversification, reinforcement of the private sector and reengagement with the International Monetary Fund.

Political regimes

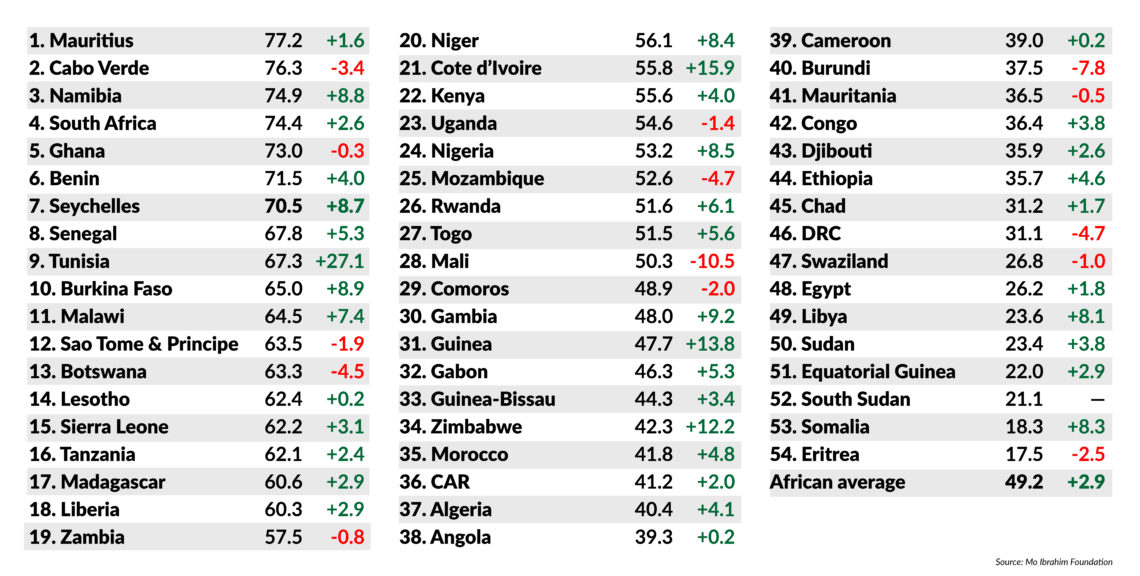

According to the 2018 CPI, Somalia is the world’s most corrupt country. Besides Somalia, five African countries are among the bottom 10 performers: South Sudan, Sudan, Guinea Bissau, Equatorial Guinea and Libya. According to the Fund for Peace’s 2018 Fragile States Index, South Sudan and Somalia are the world’s most fragile countries; Sudan is on “high alert,” Guinea Bissau and Libya on “alert” and Equatorial Guinea – a country under an authoritarian dictatorship – is on “high warning.” Seychelles, Botswana, Cabo Verde, Rwanda and Namibia, in turn, are the least corrupt countries in sub-Saharan Africa, according to the 2018 CPI. Cabo Verde, Namibia and Seychelles are also among Africa’s top performers when it comes to human rights and participation, according to the 2018 Ibrahim Index of African Governance.

Some cases suggest that strong institutions and economic freedom may be as important as democracy.

Consolidated democracies have lower corruption levels, while dominant party and authoritarian dictatorships tend to be more corrupt. The explanation is simple: remaining in power indefinitely is an expensive business, especially in a time when the political costs of open state violence increase. It takes money to use more subtle strategies. In countries where elections are not free and where there is no clear distinction between private and public, the best way to remain in power is by sustaining power structures, especially the military and security services.

However, some cases suggest that strong institutions and economic freedom may be as important as democracy. Rwanda, which is not among Africa’s most democratic countries, is perceived as less corrupt than South Africa. Despite its democratic deficit, Rwanda ranks first out of 54 countries in the Ibrahim Index’s Transparency and Accountability category and second out of 54 countries in Sustainable Economic Opportunity. Sub-Saharan Africa confirms the negative correlation between economic freedom and corruption: Africa’s less corrupt countries score top positions when it comes to economic freedom, according to the Fraser Institute’s 2018 Human Freedom Index.

Scenarios

Corruption – both in Africa and around the world – is expected to become increasingly visible and relevant for political developments, reflecting three strong trends which will likely continue. The first is increasing access to information and the resultant rise in public scrutiny. The second is the enactment of anti-corruption legislation, both in the private sector and at the state and multilateral levels. While such legislation does not guarantee that corruption will be exposed, the increase in coordination efforts and information sharing mechanisms will likely raise awareness and visibility. Finally, while globalization has increased the opportunities for corruption, as well as its scope, it has also made misconduct more difficult to conceal.

Considering this, we can anticipate two distinct scenarios:

Adaptation without transformation

Under this first – more likely – scenario, future anti-corruption efforts would become comparable to the democratization efforts of the 1990s. Anti-corruption and probity will become a new paradigm, reshaping institutions, political rhetoric and political agendas. However, in several African countries, this new paradigm will not lead to substantial transformation but rather to strategies for adapting to the demands of populations, foreign investors and multilateral organizations. These strategies could gain momentum if the global leadership crisis accelerates, in an era marked by polarization in the European Union and the United States.

The map of corruption in sub-Saharan Africa will remain heterogeneous: in countries where relatively low corruption levels coexist with democracy and strong institutions, the situation is expected to hold steady or even improve. In countries with dominant parties or authoritarian dictatorships, the anti-corruption drive will likely be used for political purposes, either to neutralize the opposition or to accelerate power changes through populist campaigns. Persistent corruption will threaten or delay the achievement of important regional goals. These include closing Africa’s infrastructure gap (private investors will be deterred by the high risk, while the efficacy of public spending will remain low) and implementing the African Union’s Agenda 2063.

Substantial transformation

This less likely scenario would be driven by a combination of factors leading to a drop in corruption levels throughout the region over the next decade. This “perfect storm” includes both political and economic drivers: mounting popular pressure – eventually leading to regime change in countries like Sudan or Malawi – and/or better leadership from a new generation of politicians; an increase in the political and economic costs of corruption; and slow but steady income growth in countries like Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa, reducing the marginal utility of corruption.

Even under this best-case scenario, large-scale and endemic corruption will persist in Africa’s most fragile states. In some authoritarian regimes, it will be increasingly difficult to interrupt the vicious cycle under which leaders do not relinquish power because they fear persecution.