The future of macroeconomic policy

While the scale of the pandemic requires government intervention, it is worth asking what the consequences of those rescue measures will be. Left unchecked, some European countries’ bloated public sectors could become even less efficient as a result of Covid.

In a nutshell

- Governments have responded to Covid-19 with aggressive intervention

- These practices could prove difficult to abandon once the crisis comes to an end

- Helicopter money and Modern Monetary Theory could become go-to solutions

This report is part of a GIS series on the consequences of the COVID-19 coronavirus crisis. It looks beyond the short-term impact of the pandemic, instead examining the strategic geopolitical and economic effects that will inevitably be felt further in the future.

The COVID-19 crisis began as a supply shock caused by the lockdown to contain the spread of the virus. But when businesses shut down and unemployment rises, a negative aggregate demand shock rapidly arises, making it difficult to disentangle the two effects. Given the enormous economic disruption caused by the pandemic, economists widely agree that authorities should carry out monetary and fiscal interventions to soften the blow and avoid a depression.

In the United States, the Federal Reserve lowered interest rates and launched quantitative easing (QE) measures to increase liquidity in the economy and facilitate credit in the hope of avoiding personal and corporate bankruptcies. In the European Union, the European Central Bank offered an 870 billion euro package as well as more regulatory flexibility for loans granted by banks, especially for small and medium enterprises. Going forward, helicopter money could be used. The Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act, signed in March by U.S. President Donald Trump, amounts to a huge $2.2 trillion fiscal stimulus that includes “stimulus checks” to households. In other countries, governments duly postponed citizens’ social security, tax and utility payments.

Ratchet effect

Despite their necessity given the emergency situation, the magnitude of the interventions raises the question of their long-term consequences. Government tax revenues are collapsing as consumption and production freefall. Indirect, VAT-style taxes and household and company levies are melting rapidly. This puts governments in a tight spot. When gross domestic product (GDP) falls, public debt automatically increases.

Monetary and fiscal policies might intermingle even more than they have in the past 12 years.

It is obvious that monetary policy will have to rescue fiscal policy. This means the crisis will greatly strengthen trends already present since the 2008 crisis or earlier: more interventionism, more bailouts, more direct and indirect government control. Monetary and fiscal policies might intermingle even more than they have in the past 12 years.

Two opposite scenarios could emerge. In the first one, given the extraordinary medicine, the “patient” will become addicted. This means the much-awaited end of the sanitary lockdown may not take us back to normalcy. In his 1987 book Crisis and Leviathan, economic historian Robert Higgs demonstrated how governments tend to inflate during crises, both in size and impact, and never go back from there – the so-called “ratchet effect.” The other scenario sees the crisis as a screening phase for bad governance and lack of accountability, offering a chance to revitalize democracy.

Scenarios

Scenario 1

On the left and far right, many citizens will seize the opportunity to blame the “neoliberal virus” in a confused, mixed-bag analysis decrying the dangers of globalization (and the supposed need to reshore all activities) and the “dying” public health service (forgetting current spending levels, as well as the private sector’s welcome innovation and production capacity during the pandemic). According to these factions, the superiority of socialism over capitalism and globalization will be demonstrated by governments coming, yet again, to the rescue of the economy (notwithstanding several governments’ failures during the crisis). One should not underestimate the nationalist dimension of this type of socialism, which could have far-reaching political consequences.

The risk of an EU implosion is now serious.

With various programs of temporary income subsidies and proposals for money dropped directly into people’s pockets on a one-off basis with “stimulus checks” (approved by the U.S. Senate on March 27), Universal Basic Income (UBI) should become even more popular than it has been in recent years. But UBI is not the miracle solution that its left and right-wing advocates presuppose. It would end up weighing heavily on public finances and weaken democratic accountability given the dependence it would create – which would lead to even less fiscal responsibility.

The public sector, especially the public hospital unions in some countries, are already using the crisis to request more government funding. They are clearly in a position to do so. “Thank you NHS” placards have become common in the United Kingdom. In France, President Emmanuel Macron, who recently called on the police to contain nurses protesting his reforms, now had to praise them as heroes of the nation. He promised them a massive investment plan and substantial pay raises.

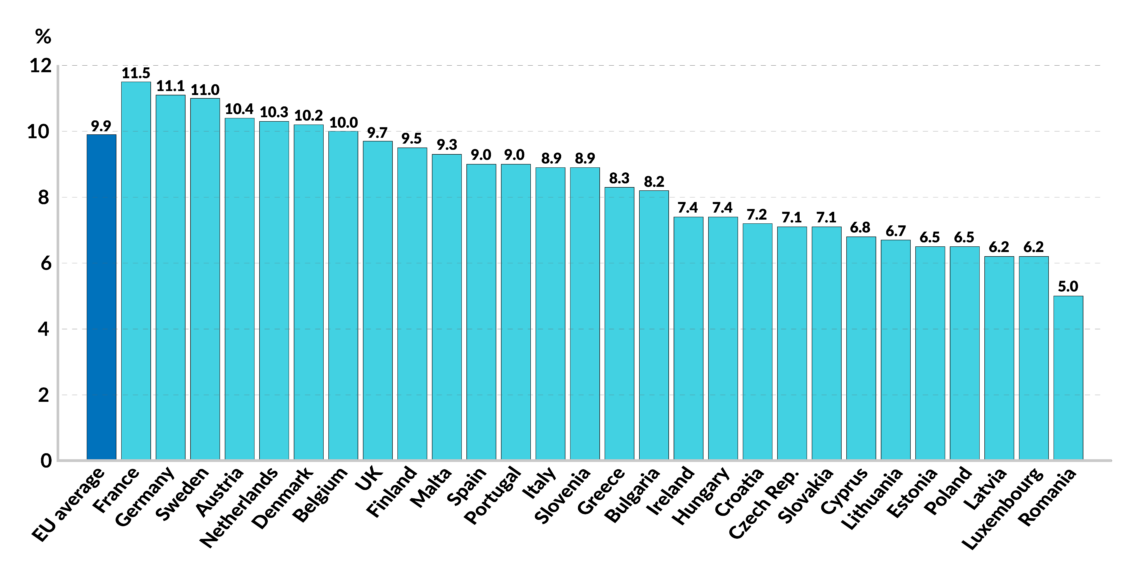

Of course, in most countries hospital workers deserve better working conditions and higher remuneration. However, international comparisons show that in many places money is spent neither wisely nor efficiently in hospitals. A study by the Institute for Research in Economic and Fiscal Issues shows an important discrepancy between France and Germany in health services provided for the same amount spent (number of beds, nurses per patient and so forth). These are caused by the costly growing bureaucracy in French public hospitals over the past two decades. The right policy would be to spend better, not more, following the subsidiarity principle – decentralized schemes generate more accountability and care efficiency.

Facts & figures

Public bureaucracies would obviously benefit from more public spending. After all, as Rahm Emanuel, then White House chief of staff, famously said in 2008, “never let a good crisis go to waste.” Public choice analysis is clear: more redistribution means governments will acquire more power. As Professor Higgs demonstrated, several programs created during the Great Depression went on for decades after the crisis. Cronyism and collusion would feed overlarge bureaucracies with barely any democratic oversight.

In Europe, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen suspended the Stability and Growth Pact rules (which had only been partially respected in recent years anyway) on March 20. Several European countries are getting more vocal about coronabonds and call for solidarity. With Russia and China helping Italy, the risk of an EU implosion is now serious and could be used to blackmail a reluctant German Chancellor. An increase in EU bureaucracy – and its costs – is thus still in the cards.

The private sector could also lobby in favor of large fiscal deficits during the crisis. Many sectors based on travel and tourism – from airlines to hotels, but also transport, shale oil companies, maritime shipping, and all the affiliated banks – will probably take a long-term hit and request bailouts. Such conditions are ideal for collusion and cronyism. Analysts are already wondering why the CARES legislation has allocated $60 million to NASA and $25 million to the Kennedy Foundation. According to others, the “alphabet soup” of the Fed rescue plan has already nationalized part of the U.S. credit market.

Given the already enormous public debt and crumbling tax revenues, some economists advocate more helicopter money and monetization of public debt to finance expansionary fiscal policy. But in the context of all the pressures listed above, it is very likely that this monetization will become a permanent feature of macroeconomic policy, leading to an infinite “fiscal QE” as economist George Selgin calls it. Over the past five years, the comedy of the Fed’s normalization policy has shown how hard it is to reverse even traditional QE.

Modern Monetary Theory, a heterodox economic theory that advocates the monetization of fiscal policy, could go mainstream. This would probably not bode well for accountability – and democracy.

Scenario 2

A more optimistic scenario could emerge. The lack of public spending reform and the perpetual postponing of fiscal balance – not to mention fiscal surpluses – are now revealing their true cost. The doctrine of “automatic stabilizers” posits that the government puts money aside (surplus) in good times and spends it (deficits) in bad times. Obviously, in places where there have not been surpluses for many years, the mechanism cannot work and a crisis like the current pandemic becomes an existential threat. Inadequately prepared countries are also often those with large deficits.

Executive powers and the various agencies with highly paid bureaucrats that have either created regulatory obstacles to market solutions (think of the Food and Drug Administration in the U.S.) or have clearly not done their job (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in the U.S. or regional health agencies in France) have been criticized. In France, the battle between the Parisian medical establishment and independent Professor Didier Raoult in Marseille over hydroxychloroquine as a treatment for COVID-19 has also created mistrust toward the elite.

People now want to hold public decision makers accountable.

This crisis could give doctors and nurses sufficient leverage to request more efficiency and a reduction of bureaucracy in both hospitals and agencies. People have begun to wonder why, despite hundreds of billions of euros invested in health, simple surgical masks are not available. More generally, public finance mismanagement in France and Italy, for instance, seems to correlate with the magnitude of the catastrophe during the current epidemic.

People now want to hold public decision makers accountable. That is a good thing for democracy because citizens will notice the costs of bureaucracy and intervention, as well as the often ill-chosen priorities into which their money is invested. No longer victims of the “fiscal illusion,” they will realize that their costly health system is inefficient. This movement toward a sound re-appropriation of public spending could boost civic responsibility – a step toward fiscal responsibility and democratic accountability.

To rebound after the crash, societies will need more flexibility and freedom from stifling bureaucracies. The unsung heroes of this crisis are the volunteers, the small entrepreneurs and companies churning out 3D-printed face shields, makeshift ventilators or hydroalcoholic gel – civil society in a market economy at its best. These phenomena could help prevent the first scenario described.

The probability that the positive forces of the second scenario will counter the negative trends of the first is not negligible for an optimist, provided sound economic education is available on the market of ideas.