Borderless money in a hot, flat and crowded world

Countries are beginning to realize that they can benefit from more inclusive forms of device-centric money, payments and financial services.

In a nutshell

- Many governments are considering digital currencies

- CBDCs are unlikely to replace traditional money

- Rather, they could accelerate innovation in finance

Until recently, the idea that the world would be locked in a digital-currency space race seemed like an abstraction or science fiction. Yet today 105 countries, representing 95 percent of the world’s gross domestic product (GDP), are either researching, prototyping or deploying a digital national currency.

This does not necessarily mean the digital currency race will be won by the public sector, but rather that countries around the world still fear being left in the dust if big tech enters the digital currency market. While one public sector fear was never realized with the abandonment of Meta’s Diem project (formerly Libra), the other – that China would launch a digital renminbi – has come to pass and has raised the stakes for many countries to keep pace.

Digital currency space race

China’s e-CNY debuted at the Beijing Winter Olympics and according to some estimates more than 300 million active accounts may already be using it. By itself, the number of users may not be a cause for geopolitical concern, since much of the motivation for the People’s Bank of China’s (PBOC) digital currency efforts are domestically focused and aimed at putting the country’s big tech players in check. The real concern is that Beijing’s digital currency could result in a parallel payment system that may not be responsive to international norms, including post-9/11 financial crime compliance and sanctions regimes.

Whether or not to implement a CBDC remains a deep technological, policy and regulatory debate, with many complex and not yet fully understood risks.

These regimes, like the current technologies that move value around the world, are looking decidedly antiquated and vulnerable. Yet, as economic sanctions against Russia have demonstrated, countries do not weaponize their currencies, but rather the underlying delivery mechanisms. When it comes to geopolitics and economics, the payment system matters more than the amount transferred.

As value transfer becomes not only digital, but also distributed and decentralized with the emergence of device-centric banking and payments (and software-intermediated capital markets), borders may soon disappear. Digital money has met Thomas Friedman’s hot, flat and crowded world and central banks are none too pleased with the prospect of eroding monetary sovereignty or accelerating digital dollarization.

The demise of cross-border payments

If the internet democratizes access to knowledge and information through the removal of friction and traditional intermediaries, blockchain-based financial services (what some refer to as Web3) may chart a similar course for the movement of money. We do not send cross-border emails, but rather exchange freely and globally with trusted counterparties. Payments could become equally borderless as both retail and institutional adoption of digital currencies continues to grow.

If Web3 augurs the emergence of an internet of value, it would stand to reason that Western values of democracy, openness, trust and transparency should be hardwired into its code and conduct. This may well be the technological contest of our times, with close parallels to the 5G wars. The choice of standards and hardware and software providers could closely align to either an open vision for connectivity and competitiveness, or an authoritarian one.

Facts & figures

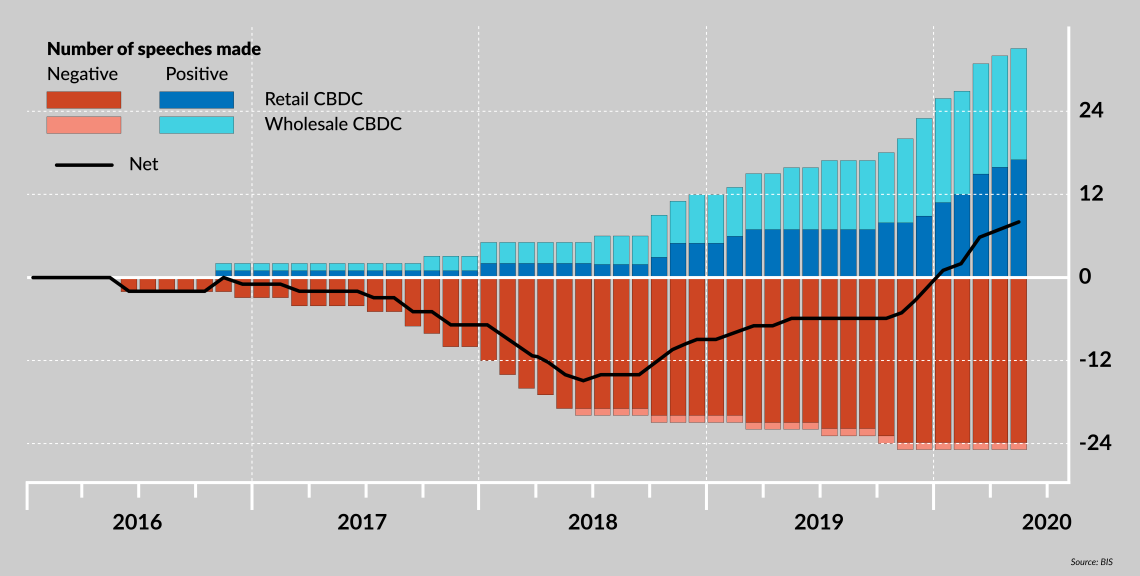

Increasingly positive perceptions of central bank digital currencies

To CBDC or not to CBDC

In the face of these choices, central banks around the world are wrestling with questions about how and whether to launch central bank digital currencies (CBDC). While the concept of a nationally issued digital currency is not new, based on central bank speeches, the idea only came into favor in the summer of 2019, the very time Libra was announced (possibly catalyzing China’s national blockchain strategy).

Whether or not to implement a CBDC remains a deep technological, policy and regulatory debate, with many complex and not yet fully understood risks. Some countries are beginning to question the merits of turning central banks into retail banking institutions, not to mention the specter of central banks becoming an economic monitoring device. This much was clear in the United Kingdom’s parliamentary inquiry on CBDCs, which deemed the idea of a CBDC “a solution in search of a problem.” Others appear to be advancing apace.

Responsible digital currency innovations are unlikely to destabilize their underlying reference currency or erode monetary sovereignty.

Meanwhile, major economies are starting to turn away from the idea that the private sector has no role to play in responsible digital currency innovation. Rather, some of the world’s largest and most sophisticated economies, from the United States, to the state of California (the fifth-largest economy in the world), to the UK, (where Queen Elizabeth II mentioned digital assets in a recent speech), to Singapore, are espousing whole-of-government approaches to Web3 economic competitiveness.

In a world where global financial needs do not take bank holidays, while traditional analog brick and mortar financial services have reached a point of diminishing returns, embracing always-on device-centric financial services should be a natural priority – even if these innovations cross borders and traditional boundaries. Indeed, the lack of broadly available open technology-powered services (digital public goods) proved to be a major pre-pandemic vulnerability amounting to nothing short of a Great Correction.

Scenarios

Like the original space race, the ongoing digital currency race is not a zero-sum game where one country wins at another’s expense. Rather, the whole world can benefit from more inclusive forms of device-centric money, payments and financial services. By this measure, the U.S. is currently ahead and the dollar is fast becoming the currency driving responsible, rules-based free market internet innovation. Money after all, whether physical or digital, relies on market trust in its underlying institutions.

Another likely scenario following the normalization and harmonization of digital currency is not that it will substitute traditional banking and money, but rather accelerate innovation in this sector. Notably, privacy could be improved through preserving digital and decentralized identity standards, as well as through an open-source technological road map for a veritable HTTP (hypertext transfer protocols are the set of rules enabling file transfers on the internet) standard for the movement of money on the internet. Neither of these standards would compete with traditional systems.

Responsible digital currency innovations are unlikely to destabilize their underlying reference currency or erode monetary sovereignty. Rather, the sum of these innovations would complete a lot of unfinished work in the global economy, potentially reaching the billions of people who cannot currently access the formal banking system – which is in itself a source of deep global instability and risk.