Taxing the digital economy

Fear countries’ own digital tax has led to an alternative at the OECD. The new proposal would abandon the tax’s connection to the business location and would work toward an international minimum tax on corporate profits. If the plan succeeds, consumers may pay the price. If not, the tax rates will remain low and promote investment.

In a nutshell

- The new OECD digital tax plan would have dramatic effects

- A failed EU effort has led to unilateral tax policies

- The new proposal would decouple digital taxes from location

- It also works toward a global minimum tax on corporate profits

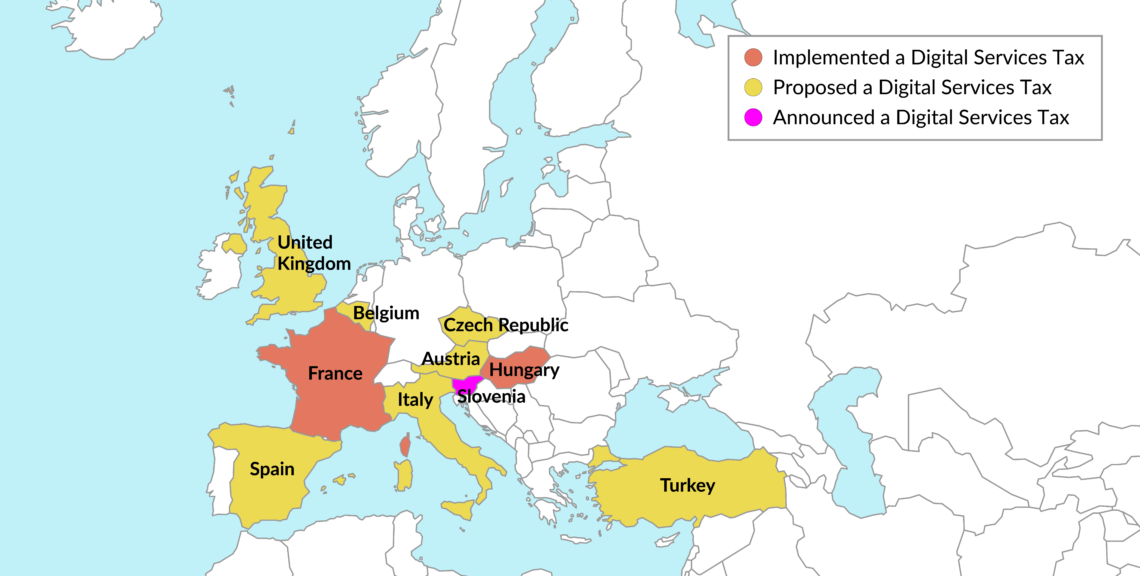

Last year the European Commission (EC) proposed a new tax on digital transactions, set at 3 percent of revenues from online advertising, sale of user data and facilitated user interactions. The proposal was unable to gain consensus support. This year, more than 10 countries have proposed unilateral domestic variations on the EC proposal and France has implemented the tax for 2019.

The growing prevalence of digital services taxes has motivated an international effort – led by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) – to rewrite the global tax rules, with the goal of addressing how to levy taxes in the digital economy. The current proposal has two pillars. The first is based on a new method of allocating a portion of consumer-facing corporations’ profits based largely on sales, rather than on business location – abandoning the corporate tax’s connection to physical location.

The second pillar proposes several changes working toward an international minimum tax on corporate profits. The OECD proposals would be a dramatic policy shift, with long-lasting effects that could lead to higher and less efficient business taxes worldwide.

Gross receipts taxes

New taxes on gross receipts are economically costly and likely not a sustainable source of revenue for unilateral actors in the long term. In most cases, the new digital taxes are more a bargaining tactic than serious proposal. Singling out profits from specific businesses or activities for special taxes is poor policy, and business taxes should generally be equally applied, without penalizing or preferencing one type of activity over another. Many of the proposed taxes go further, taxing a firm’s digital revenues as well as its digital profits.

Revenue-based taxes are economically problematic in their own right, because tax rates across similar businesses can vary dramatically depending on profitability and business structure. A start-up business could earn no profits after accounting for their costs and still be subject to a tax on their gross receipts, resulting in effective tax rates above 100 percent. Some of the proposed taxes attempt to alleviate this problem but do so ineffectively.

Many of the proposed taxes go a step further, taxing a firm’s digital revenues in addition to its digital profits.

The cost of unilateral digital service taxes is largely passed on to domestic consumers through higher prices, as with a tariff or excise tax. Given the high economic costs of these taxes, it is encouraging that countries considering unilateral digital taxes are also committed to an international alternative. Without a global solution, countries like France seem to realize that they cannot sustainably increase business taxes on their citizens without the help of the United States and the OECD. Government and business leaders are indulging in the fantasy that unilateral action is sustainable, paving the way for a severing of the link between location and taxes.

The OECD alternative

The current urgency of the OECD process is driven by the concern that countries around the world will begin unilaterally implementing digital levies, following in the footsteps of the French digital services tax and India’s equalization levy on online advertising and revised permanent establishment rules. The manufactured instability in the current system is driving an OECD alternative to unilateral action.

Countries pushing for expanded taxing rights are motivated by two different goals. Most prominently, certain European politicians seek to tap into an anti-U.S. and anti-big business sentiment, by finding new ways to levy higher domestic taxes on foreign firms. Following the failure of the EU digital services tax proposal to gain consensus, France has taken the lead, with a unilateral turnover tax on digital revenues.

The more fundamental challenge to the existing system comes from jurisdictions that seek to expand their tax base and thus generate more revenue. Countries like India can do this by linking business profits to the large numbers of consumers who use online services provided by businesses with little direct connection to the country, and thus register relatively little traditional taxable income. The ongoing OECD process is no longer just about base erosion or profit shifting per se — it has become an entirely political debate about the appropriate division of taxing rights.

The OECD consensus plan seeks to overlay, on top of the existing accounting rules, a new formula-based system to distribute estimated residual digital profits and allow countries to levy a minimum tax on international profits. These additions to the existing system will open the door to a more radical rewrite of business taxation and put new levels of complexity on an already overly complex system, without fully addressing the concerns of the countries pushing the OECD process forward.

Continued instability

The OECD’s goal to “stabilize” the international tax system is incompatible with abandoning the requirement for physical presence. Any consensus solution to allocate a portion of profits based on consumers or users will likely be an unstable compromise that will quickly precipitate a world of unilateral expansions of the OECD system, resulting in higher taxes on all businesses.

The proposal is essentially a multilateral consensus to use a standardized apportionment formula for certain profits. In the U.S., this system has given way to unilateral revisions. Apportionment, even when not standardized, can simplify the currently complex system and, when constrained by physical presence, may even facilitate tax competition. However, when the formula is disconnected from business location, countries are able to export their tax burden to firms and entrepreneurs outside their borders. Individual governments will always look for ways to expand their tax base, and destination-based apportionment — without regard for business location — makes this easier.

Following the OECD’s relatively narrow reforms for certain digital profits, populous consumer countries will still want a more comprehensive reallocation of taxing rights to the end user, and origin countries will want to protect the tax connection to employment, investment, and physical location. However, once the existing connection to business location is undermined, there is no logical place to stop the reallocation of profits by some other system. Countries that think they can increase their revenues through the change will always want to expand the portion of profits allocated based on end users.

The OECD dispute resolution mechanisms that would serve as the backstop to keep countries from abusing the newly provided data and framework are insufficient to stop newly empowered unilateral actors from expanding their share of profits. The OECD process relies on soft diplomatic power and international norms to maintain a functioning dispute system and police the current transfer-pricing regime. The current unilateral actions taken by France and India, and threatened by others, show how fragile any new system will be. As soon as a few countries decide they want to move more fully to a user-based formula, they will have a powerful precedent to act outside the OECD framework. The dispute resolution system and treaty network are only as strong as the parties’ commitment.

A successful OECD process resulting in a new apportionment system for residual digital profits will only be a temporary equilibrium. The power of unilateral action as a cudgel for reform has proven effective. Countries that want taxing rights entirely allocated to users or consumers will be emboldened to use OECD tools to determine a new tax base with greater ease, and then act on their own again.

A fully unraveled OECD process resulting in a destination-based, corporate income tax apportionment regime could remove the incentive to keep corporate tax rates low and reward countries that lack innovative and entrepreneurial business sectors due to bad policy choices. In most models, destination-based taxes are less susceptible to the competitive pressures of capital mobility and business location decisions, allowing business tax rates to rise. Coveting the American industry, and the tax base that comes with it, is not a legitimate reason to overturn the international tax order. Abandoning physical permanent establishment would reward poor policy, like digital services taxes on gross receipts, by giving countries a new tax base simply because they have an internet-connected citizenry.

Minimum taxes

The second pillar of the minimum tax proposal would only increase the economic costs of moving toward a destination-based formula for corporate tax apportionment. In the abstract, setting a minimum global tax rate and empowering countries around the world to increase taxes on foreign profits that are arbitrarily labeled as undertaxed will neuter competitive pressures to keep tax rates low.

Consumers and workers will see higher taxes passed on to them through higher prices and slower wage growth.

Sovereign decisions in designing business tax systems could be in jeopardy. Countries that understand that business taxes are borne by workers through lower wages might want to have no corporate tax or levy a simple, low rate. Other countries, like Estonia and Latvia, have reasonably high statutory tax rates, but only tax business profits when they are distributed to shareholders. These systems carry significant economic advantages.

Minimum taxes that allow other countries to punish sovereign domestic policy decisions to keep business taxes low and economically efficient would eliminate the benefits and incentives of good tax policies. A minimum tax would buttress the reapportionment of taxing rights by giving high tax countries, as well as populous consumer countries, greater ability to tax businesses outside their borders at economically inefficient tax rates.

The future of international taxation

The future likely holds one of two paths for international tax systems. Neither will be good for consumers or workers, who will suffer when higher taxes are passed on to them through higher prices and slower wage growth.

The OECD-proposed minimum tax and overhaul of physical presence rules will require the cooperation and consent of the largest economies in the world. Achieving this kind of collaboration is still an unlikely outcome. Simply getting such a proposal through the U.S. Congress, let alone legislatures in the rest of the world, would be a herculean task in the current political climate.

However, if the OECD process does succeed, effective tax rates will quickly rise for many large multinational firms, as the new system is designed to make highly digitalized firms pay more tax. In the medium term, the OECD system will be unstable as consumer countries will continue to agitate for a more comprehensive reallocation of taxing rights based on consumer location. As global profits are increasingly taxed based on consumers, and global minimum tax rates are enforced, domestic tax rates will rise as the pressures of tax competition wane.

In the more likely outcome that no consensus is reached through the OECD process, the historical consensus that business location matters will still be eroded. Businesses and countries, including the U.S., have conceded through the current OECD process that a new system is needed. Unilateral digital taxes and other extraterritorial threats will continue as a way to keep the pressure up for broader international change, but they will likely not be implemented beyond a few countries.

If international efforts to increase tax data collection and sharing continue to proliferate, they will provide the tools necessary for countries to fish for more tax revenue, especially from businesses outside their borders. International taxation will continue to be chaotic. However, as long as there is no consensus on how to overhaul the current international system, global effective tax rates will likely remain low, promoting investment and growth.