A fragile alliance in the DRC

President Tshihekedi came to power thanks to an agreement with former president Kabila, who ruled the DRC for nearly two decades and still holds sway over much of the country. If the pact remains, President Tshihekedi could implement reforms that improve the economic potential of the DRC, but far-reaching political change is unlikely.

In a nutshell

- President Felix Tshisekedi and former President Joseph Kabila are sharing power in a coalition government

- The fate of their alliance will influence the DRC’s political scene for years to come

- Rising mineral prices could present a window of opportunity for the Congolese economy

Eighteen years after coming to power and two years after the end of his mandate, Joseph Kabila joined the list of long-standing African leaders forced to hand over the presidency. A combination of constitutional limits as well as international, regional and domestic pressures – epitomized by the popular slogan “Kabila must go” – gave him little choice but to stand down after the December 2018 elections. But even under new leadership, prospects for meaningful reforms remain low.

Informal alliance

While the end of President Kabila’s rule was met with relief by both regional and international leaders, opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi’s victory was far from consensual among the Congolese opposition and civil society. Reasonable doubts remain about the transparency of the electoral process, and it has become clear that the results derive from an informal alliance established between Mr. Kabila and his former rival.

Until recently, President Tshisekedi was part of the Lamuka coalition – a broad anti-Kabila front that included opposition heavyweights like Jean-Pierre Bemba and former Katanga Governor Moise Katumbi. In November 2018, the coalition selected former ExxonMobil manager Martin Fayulu to run against the president’s handpicked successor, former Minister of Interior and Security Ramazani Shadary. Mr. Tshisekedi then abandoned the coalition to establish an off-the-record agreement with President Kabila and ran for president. (Amid so much political polarization and electoral competitiveness, Mr. Shadary – a low-profile politician who was under international sanctions for his role in the repression of anti-Kabila protests – stood little chance of winning.)

Opposition leader Felix Tshisekedi’s victory was far from consensual.

Three months later, President Tshisekedi and former President Joseph Kabila declared their intention to rule together as part of a coalition government. For the former, the agreement represented an opportunity to win the presidency, while for the latter it meant avoiding imprisonment and maintaining his vast legacy and political influence without having to resort to violence.

Delicate balance

The outcome of this arrangement will be determined by two factors: the first one is how Messrs. Tshisekedi and Kabila agreed to share power; the second is whether they will follow through on the plan.

Furthermore, while President Tshisekedi’s victory has been presented as the first peaceful transition of power in the DRC, reforming the country’s political system will be a daunting task. While the president holds most of the formal power, other structures – some informal – play an important role.

The DRC is the largest country in sub-Saharan Africa, and with nearly 80 million inhabitants, one of its most populated. Non-state actors, especially civil society organizations, are sometimes the main providers of basic local services. In addition, rebel armed groups are key security actors in some areas. The 2015 decentralization reforms increased the number of provinces from 11 to 26, highlighting the poor performance of the country’s administrative capacity. Local and national authorities are connected by multiple patronage networks, where personal influence and capital accumulation remain prevalent.

This means that parallel power structures will play an important role in shaping the Tshisekedi presidency. It also means that former President Kabila, who was in power for 18 years, remains largely in control. More importantly, he holds considerable power over the security structures that remain relatively functional: the intelligence services, the police and the presidential guard.

Mr. Kabila’s party – the Common Front for Congo (FCC) – also controls 70 percent of the National Assembly (with 337 out of 500 seats) and the majority of provincial legislatures. Meanwhile, President Tshisekedi’s Cape for Change (CACH) coalition only secured 46 seats. This discrepancy between the presidential and legislative results reinforced suspicions of a pre-electoral agreement.

Not surprisingly, the formation of the government and the appointment of the Prime Minister (chosen by the FCC) were extremely slow. The new executive has 65 ministries, 42 from the FCC and 23 from CACH.

Tale of two countries

In the DRC, widespread poverty and state inefficiency contrast with the country’s huge economic potential. Approximately 73 percent of the population lives on less than $2 per day. Despite some progress over the last decades, the country ranks 176th out of 189 countries in terms of human development indexes. Corruption is widespread and pervasive: the country ranks 161st out of 180 in Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index and, according to a 2019 survey, an estimated 80 percent of public services users have paid a bribe in the previous 12 months.

Instability on the security front also hinders development. Eastern Congo remains the epicenter of a long-standing conflict involving an estimated 70 armed groups. The Mai-Mai militias, which have strong historical and political roots in the area, continue to perpetuate violence in the name of a vague agenda of “self-defense” and liberation.

The Congolese army managed to neutralize the leadership of the Democratic Forces for the Liberation of Rwanda (FDLR), mostly formed by Hutu rebels. However, security in eastern Congo is threatened by an Ebola outbreak in North Kivu that has already claimed more than 2,000 lives – the world’s second-largest epidemic on record. In the south-central region of Kasai, intercommunal violence, perpetrated by groups like the Kamwina Nsapu and Bana Mura, has displaced more than 1.4 million people since 2016. In the mine-rich Katanga Province, which accounts for 71 percent of the country’s revenue, autonomist aspirations have reemerged in the past years, further eroding the legitimacy of the central state. In the northeastern region of Ituri, long-standing tensions between Lendu farmers and Hema herders began escalating in June 2019. Unsurprisingly, the economy remains heavily militarized and state legitimacy is weak.

The country has economic potential and a growing middle class.

But a more enthusiastic narrative is also taking shape. The country has economic potential and a growing middle class. Despite multiple risks and an extremely adverse business environment (the DRC ranks 183rd out of 190 economies in the 2020 World Bank Doing Business Report), it continues to attract foreign investors.

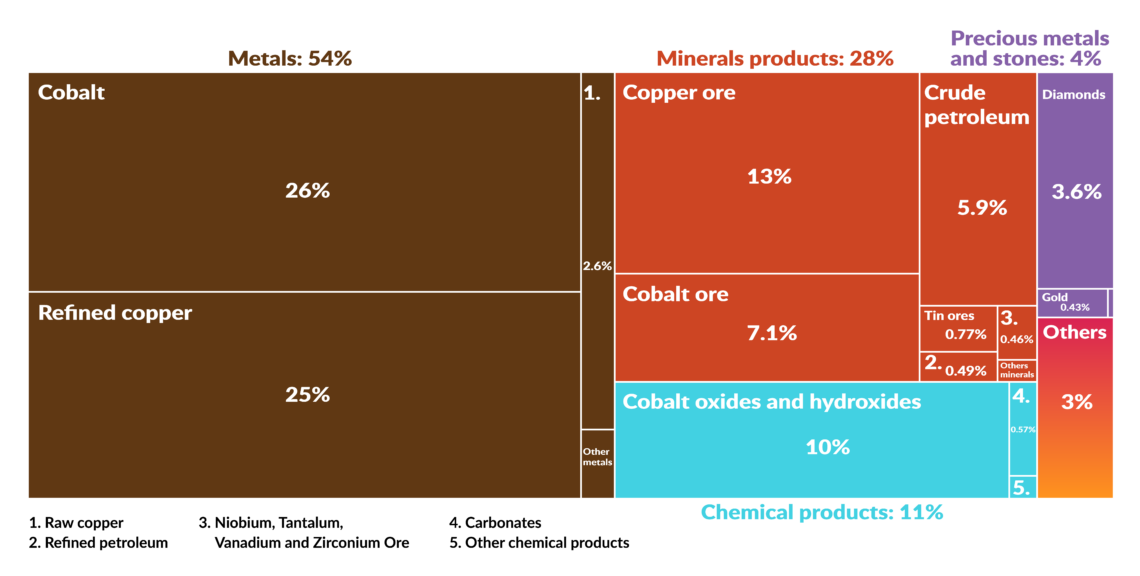

The explanation lies in the country’s mineral wealth. The DRC is Africa’s biggest producer of copper and cobalt – a key component of lithium-ion batteries, crucial for the automotive and energy storage industries. The two minerals account for three-quarters of the country’s annual exports. In 2018, it was the source of some 69 percent of the world’s cobalt supply.

Under the most likely global economic scenarios – especially as the “green economy” accelerates – demand for cobalt will probably increase in the next five years. The DRC will likely remain an important geoeconomic player. Chinese companies are investing in the region, which is key in Beijing’s ambitions to become a high-end producer of goods. Seven of the largest mines in the DRC are Chinese-owned.

Scenarios

Despite difficulties resulting from his opaque power-sharing agreement, President Felix Tshisekedi seems committed to political reforms. He released political prisoners and allowed the return of political exiles, including outspoken opponents like Moise Katumbi and Sindika Dokolo. Political opponents are given more freedom than under President Kabila. President Tshisekedi has also affirmed his commitment to economic diversification, regional integration and better conditions for business.

Concrete steps – like simplifying access to visas and reducing the time and costs of opening a business – have been taken, but it is too soon to determine whether the government will follow through with more critical changes. However, there is at least one front where palpable progress has been made. The rapprochement between the DRC, Rwanda, Angola and Uganda – as seen at the July 2019 summit on regional security and development – and potential membership in the East African Community represent a significant shift. The latter will likely affect not only the regional outlook, but also the DRC’s internal balance of power, in favor of President Tshisekedi.

Under the most likely scenario, the agreement between Mr. Tshisekedi and Mr. Kabila will hold in the short term thanks to convergent interests. While former President Kabila will retain significant power over both formal and informal power structures, regional and international pressures should dissuade him from openly confronting President Tshisekedi. Meaningful political and economic reforms – including the reform of the Constitutional Court or the dismantlement of extractive patronage networks – remain unlikely.

Yet, the agreement is brittle. Access to power in the DRC will be increasingly rewarding due to mineral reserves and potential on the global market. The political situation will probably become highly unstable ahead of the 2023 elections when Mr. Kabila, aged 53, is expected to make a comeback.