A faltering Eastern Partnership

The Eastern Partnership has lacked a strategy since its creation in 2009. Designed to promote European values in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Belarus, Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, the project has done little to reduce poverty and corruption. Furthermore, the participants have often struggled to balance allegiances to Moscow and Brussels.

In a nutshell

- The Eastern Partnership’s vague goals set it up for failure from the start

- The plan has brought no improvement to security or economic growth in the region

- Without the prospect of EU membership, countries had little reason to make structural changes

Over a decade has passed since the European Union launched its much-vaunted Eastern Partnership (EaP) program. The ambition at the time seemed laudable. The “Big Bang” enlargement of May 2004 had brought a host of Central European and Baltic countries into the EU, increasing total membership from 15 to 25 – in parallel to a similar expansion of NATO. The combined outcome was a fundamental transformation of European trade and security infrastructure.

This also raised the question of how to deal with those left out. Given that appetite for further expansion to the east was low to nonexistent, it was decided to offer a second-best alternative in the form of Association Agreements. The latter would bring willing nations closer to the EU, albeit without guaranteeing membership any time soon, if ever.

Building on the ambition of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP) to create a “ring of stability and prosperity” around its periphery, at its Prague Summit in May 2009 the EU decided to propose a closer Eastern Partnership. A group of six nations was invited, namely, EU neighbors Belarus, Ukraine and Moldova, as well as Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia in the South Caucasus.

Deep-seated hesitation

A decade later, the verdict on the project remains mixed, mainly because no clear criteria for success were set out beyond the elusive goals of friendship, value promotion and exchange of ideas.

The official stance is that the EaP has worked well – delivering on procedures such as the acceptance of Associations Agreements. Following a period of flagging enthusiasm, marked by the war in Ukraine, the Brussels summit in November 2017 adopted a pragmatic final declaration, envisioning 20 deliverables by 2020. In the run-up to the 10-year anniversary in May 2019, there was much additional soothing. In April, the External Action Service even posted a factsheet to debunk a set of “Myths about the Eastern Partnership.”

All six partner countries are marred by endemic corruption, of staggering proportions in some cases.

Less optimistic observers would conclude that the purpose of the partnership should have been to promote economic growth and good governance, to combat corruption and advance conflict resolution. From this angle, the EaP can only be deemed a failure.

Ukraine and Moldova are tied for the dubious distinction of being the poorest country in Europe. All six partner countries are marred by endemic corruption, of staggering proportions in some cases. With the exception of Belarus, they also have unresolved military conflicts with Russia. The general situation has gotten much worse since 2009.

It could be argued that blaming this on the EaP is unfair because no serious resources were ever committed toward tackling those issues. But one is then left wondering what the real purpose of the exercise was.

One thing made clear by the outcome of the EaP is the collateral damage that is bound to follow the hesitation that occurs when value promotion and hard-nosed national interest cannot be balanced. It is a trait that characterizes much of EU policymaking.

The EaP was born out of the European Neighborhood Policy (ENP), which had invited neighbors to the east and south to share visions of peace, stability and prosperity. The ENP offered real benefits to all parties involved, including an arena for member states in southern Europe to develop their own national interests, and a platform for increased cooperation with Middle Eastern and North African countries.

Strategic failure

The game plan changed because of the 2008 war between Russia and Georgia. Taking a lead in expressing harsh critique against Russia for its aggression, Sweden and Poland convinced the EU to carry out an interest-driven policy, namely providing security for countries under perceived threat from Russia. The declared ambition was to counterbalance the Kremlin’s insistence on viewing the countries in question as a “sphere of privileged interest.”

Building closer relations with countries between Russia and the EU carried risks. Russian authorities could easily conclude that the EU’s true intentions were to push them even further out of the community of European nations.

The answer from the EU was and remains that it seeks to promote its values. The accompanying mantra is that all countries have inalienable rights to choose what trade and security structures they wish to join. Russia was told, in no uncertain terms, that it had no right to interfere. The very notion of spheres of interest that is so dear to the Kremlin was anathema to political elites in Europe and in the U.S.

The main problem for the leading promoters of the EaP, foreign ministers Carl Bildt of Sweden and Radoslaw Sikorski of Poland, was that while they did secure verbal backing for the project, they failed to corral the rest of the EU behind any substantial measures. The reception was lukewarm at best. In the words of one observer, to many member states it was at best irrelevant, at worst an irritant in seeking to strengthen relations with Moscow.

Facts & figures

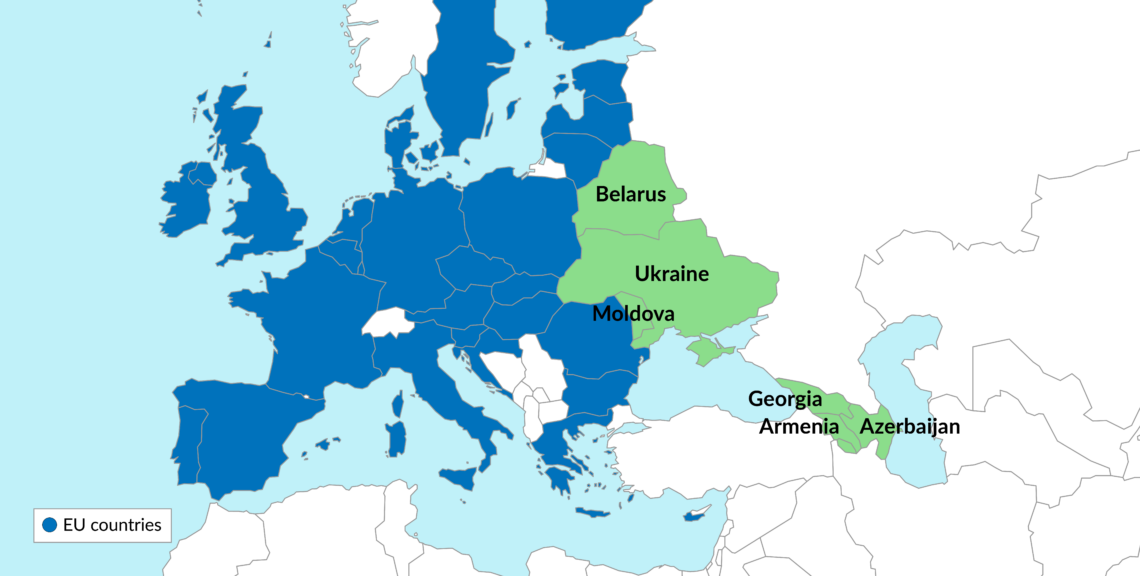

Countries of the Eastern Partnership

It was unclear whether there was adequate support amongst political elites within the designated partner countries. Belarus would prefer its union with Russia. Azerbaijan would play both sides. Armenia joined the Russia-led Eurasian Union. Even in the remaining three countries, internal tensions over how to balance relations with Russia and the EU have caused serious political tensions.

Opinion polls have also shown that less than five percent of the concerned populations are aware of the existence of the EaP; in the EU the figure is less than one percent. The implication is that this has very much been a self-serving elite project, driven by a small circle of foreign policy activists (and Eurocrats), with support from like-minded political players inside the region.

The absence of a clear vision for the partnership was highlighted by the lack of EU membership as an end goal. Proponents of the EaP believed that the mere exercise of trying to fulfill membership requirements would have benefits. This was disingenuous. Experience from former candidate countries shows that potential membership is vital in securing political acceptance of all the hardship entailed in structural adjustment.

It has also been argued that some of the countries in the EaP have indeed made progress, for example in terms of increased trade with the EU. Ascribing this to free trade agreements is a dubious argument. The main reason why some of the countries in question have recorded a rising share of trade with the EU is that trade with Russia has plummeted. And in cases where there has been an increase in the volume of trade with the EU, the main trading partners have been neighboring Germany and Poland – in the case of Moldova also Romania. The involvement of other EU member states remains insignificant.

The conclusion is that the EaP has failed to achieve substantive results simply because it never had any real chance of succeeding. There were good reasons why the partners were not given a “membership perspective.” Accepting tiny Moldova would have been possible, as a low-cost gesture of goodwill, but the very thought of admitting Ukraine was clearly out of bounds.

The main reason why Ukraine could not and will not become a member of the EU is that it is simply too large and too poor. Accepting it as a member, with full access to structural funds and agricultural subsidies would imply crowding out of vital lobby interests within the EU, mainly but not exclusively for French and Polish farmers. It is precisely for these reasons that Turkey will never join either.

Potsdam and Yalta

The most important shortcoming by far was that, in a program designed to provide security, there was no strategic vision on how to deal with Russian resentment. Many have maintained that the EU did go out of its way to ensure that the Kremlin would not feel left out, in the same manner, that many claimed that NATO did all it could to ensure that expansion would not be perceived as a threat to Russia. Again, this is disingenuous.

Although the Kremlin did at times speculate that it might join both the EU and even NATO, such speculation could only be interpreted as joining on even footing with Germany, France and the UK, or in the case of NATO, with the U.S. Any belief that Russia might desire to join a partnership with the EU as a rank and file member was an obvious nonstarter.

Russian President Vladimir Putin has given ample illustration that he remains mired in the world of Potsdam and Yalta, where the “big boys” sit together around a table and decide the future of the world. Failing to realize that this table no longer exists, he deeply resents not being offered a seat.

In a program designed to provide security, there was no strategic vision on how to deal with Russia.

In formulating the EaP, it should have been clear that further expansion was bound to deepen Russian irritation. And in contrast to the EU, Russia did have a clear strategic vision. While Brussels was busy promoting its values and soft power, Moscow was preparing to play hardball, to stand up for its interests with military force if need be.

Ukraine provides the most tragic illustration of the consequences. At the Vilnius summit in November 2013, the EU was bent on forcing Ukraine to choose EU ties over relations with Russia. It was a choice that Kiev was not able to make, for economic and security reasons. The Kremlin pushed back and the rest is history.

By the time of the Riga summit in May 2015, the game plan had again been transformed. Emphasis was no longer on expansion and the promotion of common values but rather on security and on defusing tensions with Russia.

In an interview on the day before the meeting, European Council President Donald Tusk noted that the partnership program had never entailed a guarantee of EU membership. To this he added, rather cynically, that while Kiev, Tbilisi, and Chisinau “have their right to have a dream, also the European dream,” it was not up to him to deliver an empty promise. What was on offer was merely a road toward sharing European values: “I mean not membership in a predictable future, but to European standards, to our cultural and political community.”

Scenarios

Looking forward, the Eastern Partnership will surely muddle along. Such large bureaucratic structures entail heavy vested interests and they cannot be allowed to simply disappear. We may thus expect further summit meetings to issue regular self-congratulating status reports.

In typical fashion, on November 15, 2017, the European Parliament adopted a resolution on an “EaP Plus,” designed to reward those who had made significant progress on reforms. Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine may now look forward to being included in the Customs Union and perhaps in the Schengen area. Since nothing of substance has changed, the likelihood of positive developments is slim.

The EaP may credibly claim to have achieved the promotion of intercultural exchange, and of the exchange of people that was already an integral part of the ENP. Granting visa-free travel to Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine has facilitated travel for both work and study abroad, not to mention youth mobility. It is still unclear if the impact will enhance development prospects at home, or simply accelerate the already troublesome brain drain.

Beyond all the rhetoric about soft power and value promotion, the EU remains beholden to the national interests of its member states. The fact that it has given 200 times more financial assistance to Greece than to Ukraine does illustrate that closer-to-home hard-nosed national interest remains the EU’s strategy.

No one has captured the essence of the faltering Eastern Partnership better than German Chancellor Angela Merkel. Speaking in front of the Berlin parliament on May 21, 2015, before leaving for the Riga summit, she noted that, “We must not create false expectations.” It would surely have been much better for all concerned if that warning had been issued in 2009.