Recovery economics: Optimism or overheating?

Economists Larry Summers and Olivier Blanchard have become critical of President Biden’s spending plans. Though they are right that economic overheating could prove disastrous, at least the U.S. has an optimistic outlook – unlike slow-moving Europe.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. is engaging in audacious spending in response to Covid-19

- Critics say it increases the risk of economic overheating in the U.S.

- Though risky, the plan has brought back the optimism Europe lacks

A year ago, economies experienced the worst contraction in modern history. The most optimistic scenario at the time was a so-called V-shaped recovery – a sharp decline, followed by a quick return to pre-pandemic growth.

It quickly became clear that the pandemic would not just constitute a short shock, as some experts initially thought. Wave after wave, the coronavirus continued to put economies all over the world under tremendous strain, crushing the morale of businesses and consumers. Politicians and policymakers, bogged down in a dilemma pitting public health against economic health, finally resigned themselves to the reality that a far less favorable, L-shaped (sharp decline, sluggish recovery) economic future was in store.

New optimism

Then, out of the blue, there was a drastic change of mood in the United States. The headlines were increasingly rapturous: “euphoria,” a “seismic shock,” “a return of the Roaring Twenties.” Goldman Sachs published a research note called “Anatomy of a Boom.” These are clear signs that optimism is back, even though the pandemic is far from over. No one saw it coming. Just over six months ago, the world was stunned at the images of pro-Trump rioters storming the U.S. Capitol. Joe Biden’s presidency was violently disputed before it had even begun. The country looked deeply fractured.

When it came time to mass-produce and distribute the vaccines, the tide turned.

At the beginning of the pandemic, the country’s management of the health crisis was hardly a model of success. Death rates were high, the public health system seemed overwhelmed and inefficient, and leaders denied the seriousness of the illness. The Trump administration did not have a shining record. But when it came time to mass-produce and distribute the vaccines, the tide turned. The U.S. has long excelled in large-scale logistics, and this was no exception. When President Biden took office in January, he pledged to ensure that 100 million vaccine doses would be administered in his first 100 days. A few weeks later, he doubled that commitment, and the goal of 200 million doses was met ahead of schedule, by the end of April.

Bidenomics

The economic initiatives President Biden made in his first 100 days also turned heads. The septuagenarian surprised the world with his audacity when his administration took barely a few weeks to pass a gargantuan fiscal stimulus package. The $1.9 trillion American Rescue Plan, signed into law on March 11, grants working families a $1,400 per-person check – “helicopter money,” as Milton Friedman would put it.

There is more to come. Two longer-term investment packages have been announced and await passage through Congress: the $2.3 trillion American Jobs Plan, aiming to create millions of jobs and modernize infrastructure, and the $1.8 trillion American Families Plan, which puts the priority on the education and protection of children. These three eye-popping plans intend to “build back better” the economy and achieve a significant transformation in social policy. Together, they are supposed to form an essential step toward democratizing the economy and establishing a modern welfare state.

If all goes as planned, the economy will smoothly soak up the avalanche of money. Companies will scale up their activities to meet the soaring demand. They will need to hire more workers. Unemployment rates will fall, while investment and innovation rise.

With the pandemic forcing much of life to go digital, the American tech landscape has already changed drastically. Myriad disruptive technologies are available for investment in many sectors, including finance. Creative destruction is occurring everywhere. Eventually, strong, healthy, sustainable growth will return, something the industrial world has not experienced for decades. In such a “happy” scenario, as former International Monetary Fund chief economist and MIT professor Olivier Blanchard calls it, everyone would be better off – not just Americans. The rest of the world could benefit from the U.S. recovery as well.

From stagnation to fire

However, there is plenty that can go disastrously wrong, as both Mr. Blanchard and former U.S. Treasury Secretary Larry Summers have loudly warned. It is not that these two prominent Keynesians are opposed to the idea of stimulus – quite the opposite. Since the 2008 financial crisis, they have urged policymakers to rely more on fiscal policy and less on monetary policy. The latter, they believe, is largely at the end of its usefulness.

The amount of water that is being poured in vastly exceeds the size of the bathtub.

What is wrong with President Biden’s proposal, in their view, is that it is “excessive” and “irresponsible.” The magnitude of the response should be in proportion to the scale of the problem, Mr. Summers insists. However large it might have been, the hole that Covid-19 has ripped in the economy is substantially smaller than the trillions of dollars the Biden administration plans to inject over the next decade. The “amount of water that is being poured in vastly exceeds the size of the bathtub,” Mr. Summers wrote. Policy needs to be “grounded in realities” – and “these are not,” he argued.

The most immediate consequence of President Biden’s historic stimulus could be an overheating of the economy. According to Mr. Summers, the U.S. economy is not just heating up; it is “on fire.” Curiously, Mr. Summers himself insisted for years that the American economy was trapped in what he called “secular stagnation” – a world of persistently low growth, low interest rates and low inflation. Now, he seems to have changed his tune.

Expanding bubbles

There are signs that the U.S. economy could be expanding at an unsustainable rate. Since businesses began reopening, consumers have started spending more aggressively than most forecasters anticipated. Global supply chains have been pushed to their limits. At the same time, there seems to be growing evidence of labor shortages in many sectors. The culprit, Mr. Summers says, is the all-too generous unemployment insurance extended until September. It creates incentives for people to stay out of the labor market at a time when companies need workers to return so that they can ramp up production.

In a recent press conference, U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Jerome Powell countered the claim of job shortages. The phenomenon is anecdotal, he said. After all, there are still more than 9 million people out of work in the U.S. “We don’t see wages moving up yet,” he added. What Mr. Powell cannot deny is that a sharp rise in consumer prices is already happening in the U.S. In April, they were 4.2 percent higher than a year prior. Bubbles are appearing and expanding throughout the economy: in the real estate and stock markets, and in non-fungible tokens and cryptocurrencies, for example.

Chairman Powell expresses confidence that the economic overheating is only temporary.

Even though the economy is accelerating fast, the American central bank is unwilling to raise interest rates for now. It recently announced that it would keep short-term rates at near-zero for at least a year or two. Bond buying will go on at a monthly pace of $120 billion until the economy has fully recovered. Chairman Powell expresses confidence that the economic overheating is only temporary, as is the inflation. People do not expect inflation to rise sharply in the long term because there is “still significant slack in the labor market,” he said in his April statement.

Mr. Summers, who appears increasingly frequently in American media these days, retorts that in the 1970s, the Fed also often pointed to “transitory” factors, but ended up facing a 15-year period of high inflation, the longest in modern American history. Interest rates shot up to 20 percent. The period is now known as the Great Inflation. Is Mr. Summers insinuating that the U.S. could relive such a challenging episode in the coming years?

Forced recession

Mr. Summers recently called the Fed’s wait-and-see attitude a “dangerous complacency.” His point is that inflation could spiral out of control if the central bank were to intervene too late. The specter of the Great Inflation would be looming. The Fed would then need to raise rates much more drastically than if it had acted earlier when the situation was still manageable. It would be forced to tighten monetary conditions to the point of slowing down the entire economy. In other words, it would need to fabricate a recession to break the vicious cycle of economic overheating and return prices to acceptable levels. Years of ultra-accommodative monetary policy, not to mention the trillions of dollars in fiscal stimulus, would have gone to waste.

If the biggest economic policy experiment of all time were to fail, depression could be waiting at the end of the road.

The post-pandemic American economy would be back at square one: stagnation. The secular stagnation theorist could say that America has not succeeded in breaking out of the “low-for-long” trap; the current euphoria is nothing but a manic episode of a chronic depression. If the biggest economic policy experiment of all time were to fail – which, according to Mr. Summers, is “the preponderant probability” – depression could be waiting at the end of the road.

Shock of expectations

Detractors of President Biden’s spending plans are correct on many points. Inflation could become a problem. Growth could disappoint. The stimulus may not even benefit those who need it most. There will be inefficiencies, waste of resources and malinvestment. These drawbacks are inherent to the kind of megastate that the Biden administration wants to build.

Is Europe taking a better path to recovery? Olivier Blanchard believes so. “There will be no economic overheating like in the U.S., but this is not a disaster, and may even be an advantage in the long run,” he wrote. The European strategy is certainly slower. Delays have accumulated all around. The European Union trails in vaccine rollout. The common recovery fund (NextGenerationEU), agreed upon last July, was finally ratified by all member states at the end of May. The initiative should start distributing money to national governments a full year after it was initially conceived to fight an urgent crisis.

Facts & figures

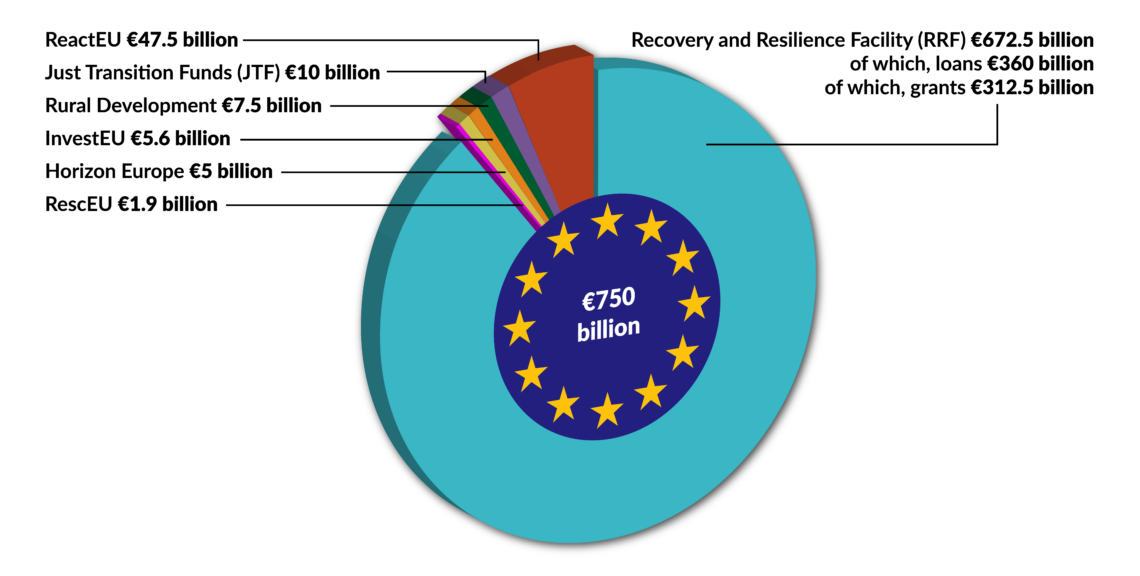

Also, the size of the European package – 750 billion euros in grants and loans – is far smaller than the American proposals, which total as much as $6 trillion. “The risk of doing too little is greater than that of doing too much. … The lack of ambition is weighing us down,” wrote Peter Praet, the former chief economist of the European Central Bank. The institution’s former vice president, Vitor Constancio, is on the same wavelength. “Washington is experimenting with policies to completely overcome the crisis, while Europe is languishing under the weight of its specters and fears,” he lamented.

Scenarios

The success or failure of the European recovery package will ultimately depend on whether beneficiaries use the money wisely. The problem is that the EU, as it so often does, is relying on governments and technocrats – rather than citizens and entrepreneurs – to restart the economic engine. It can only hope that member states spend the funds responsibly. If a government squanders the money, there is not much Brussels can do.

Furthermore, the EU’s divided member states seem unable to agree on a common prospect for the future. While some will continue adopting expansionary fiscal policy for a long while, others may eventually be tempted by austerity.

So, yes, Mr. Blanchard is correct to say there will be no economic overheating in Europe – but only because there is no genuine upswing in sight for many European nations. Instead, Europeans see stagnation and gloom in their economic future, which affects their decisions. European leaders simply have not succeeded in communicating optimism to their citizens. American leaders did.

Whatever comes of the ambitious Biden plan, it has created a formidable “shock of expectations.” This in itself is an achievement that will bear fruit. Economists know that expectations often become self-fulfilling – for better and for worse.