Scenarios for investment managers’ exploitation of ESG

“ESG” is the new buzzword in finance and investment. The initials stand for “environmental, social and governance” – three criteria deemed necessary for sustainable business. The new focus on such goals, however, also serves a new excuse for underperformance.

In a nutshell

- ESG stems from calls for “sustainable” business

- However, it gives financial executives leverage over their clients

- The use of such criteria could lead to excessive risk or fraud

In the world of finance and investment, a lot of new hype has emerged over what is known as “ESG,” or environmental, social and governance – the three factors some consider key for “sustainable” business. What began as an activist cry from the left wing of the political spectrum has become an issue of reputation for fund managers and other financial professionals. Now, Wall Street executives have discovered how to use ESG for their own personal enrichment without being held accountable. One could say ESG now stands for “executives salivate greedily.”

Before explaining how ESG has become a tool for managers and executives to pursue their own agenda at the expense of their clients and customers, it is important to set out a definition of ESG and explain the principal-agent relationship.

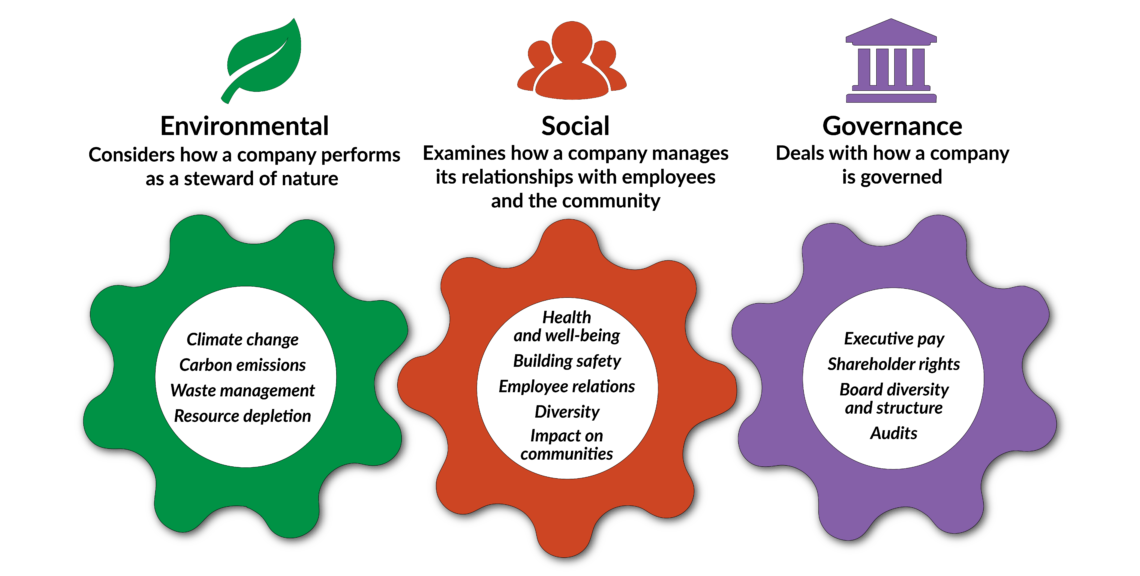

Environmental, social and governance are sets of criteria for screening potential investments. Environmental criteria are supposed to assess how a company performs as a steward of nature. Social criteria examine how it manages relationships with employees, suppliers, customers, and the communities where it operates. Governance deals with a company’s leadership, executive pay, audits, internal controls and shareholder rights. Sometimes, ESG is also referred to as sustainability. It is still an open discussion whether climate-related criteria fit into the “E.”

ESG could easily encourage financial executives to pursue their own interests at the expense of their clients.

The principal-agent relationship is an arrangement in which one entity appoints another to act on its behalf. In the world of finance and investment, the investor is the principal, and the fund managers and financial executives are the agents. In this system, the agent ideally has no conflict of interest in carrying out an act on behalf of the principal. In reality, however, agents may have several incentives to pursue their own agendas, even at the expense of the principal. While being accountable to the latter, the agent can take advantage of various asymmetries – for example in execution, information, time or fee structure.

ESG could easily become yet another asymmetry encouraging managers and financial executives to pursue their own interests rather than those of their principals. The opportunities are manifold; some are inherent to ESG and some result from the implementation process.

Facts & figures

Problems in ESG

Contrary to what its proponents suggest, ESG criteria are not clearly defined. Instead, they are full of trade-offs and value judgments arising from the fundamental conflict between the notions that the three concepts represent. On one hand, not everything that is socially desirable is good for the environment. On the other, not everything that is environmentally friendly has a positive impact on a firm’s governance.

Applying ESG principles often requires highly contextualized value judgments. An investment in a hydropower dam could reduce greenhouse gas emissions. At the same time, it might negatively affect the local ecosystem. The decision whether to invest in the dam is a trade-off between environmental priorities.

This problem is exacerbated by a lack of methodology. Different service providers and indices rank the same firms very differently. Sustainalytics, FTSE and MSCI serve as instructive examples. In FTSE’s environmental rating, electric-car maker Tesla gets the lowest possible score; in the MSCI’s, Tesla scores near the top. All aspects of ESG considered, fossil-fuels extractor Exxon outranks Tesla according to FTSE and Sustainalytics. But according to MSCI, Tesla is better at ESG than Exxon.

The arbitrariness is also manifest within the individual indices. For example, the FTSE ranks Tesla low because of the high electricity consumption of its cars and its supply chain. However, FTSE does not seem to apply the same criterion to Alphabet, the parent company of Google, a service that is dependent on electricity on both ends of its supply chain.

Herein lies the first problem of ESG: It is opaque, it lacks reliable methodologies and it is always based on value judgment. These asymmetries give the agents (managers and executives) room to impose their agendas on their principals (customers and clients).

There are several additional problems. Fund managers and financial executives have no more expertise in value judgments than their clients do. Moreover, the arrangement to which both sides agreed usually does not delegate value judgments to the agent.

Suboptimal performance

The second set of problems lies in how fund managers and financial executives use ESG. In most agency relationships, optimal contracting is a pivotal issue. Contracts give agents an incentive to optimize performance. However, agents also care about their own reputation. While the performance is shared with the principal, the reputation is the agent’s. With ESG, agents can polish their personal reputation while charging their principals for it.

In most contracts, the principal pays for expenses related to accessing data and gaining knowledge for ESG. This can either happen directly or through the agents increasing the management fee, which is independent of performance. Conforming to ESG is increasingly used to explain underperformance. In the name of these three letters, agents even change indices or modify tracking errors.

There are many ways for agents to use ESG to deviate from what their principals want.

By exploiting the lever ESG provides, the relationship between principal and agent becomes antagonistic. There are many more technical ways in which agents can use ESG to deviate from what the principals want. For example, a principal may prefer passive investments when ESG requires an active role. In captive systems like pension funds, the real principals, the insured individuals, do not even have a voice in decision-making. Moreover, the quality of ESG data is often dubious.

Some fund managers and financial executives outsource ESG processes. This on its own increases the costs for principals. Ironically, it also creates two governance problems: If ESG is as important as the agents claim, is it legitimate to outsource those processes? Moreover, if the agents that outsource are feeding ESG “gatekeepers” – a few select firms making decisions about compliance – is it good governance to encourage oligopolies?

All these arguments point to the third set of problems with ESG. It has significant potential to distort the decision-making process to the unilateral gain of the agents. Agents can embellish their reputation by creating the impression that they are making the world a better place, but they are doing it at the expense of their principals.

Remedies

What could the principals do to stop this new method, which fund managers and financial executives can use to disguise their greed? For one, they could engage in the decision-making process and challenge their agents’ motives, methods and costs. If they do not have a voice, they could do what managers fear most: inform the public.

Secondly, they could set up mechanisms to curb their agents’ room for maneuver. Most importantly, they could tie ESG-related fees to performance. Also, they could make sure that fund managers and financial executives carry not only most of the costs but are also personally liable for any underperformance originating from ESG.

Where principals have a voice in the decision-making process, they could challenge their agents’ motives

Finally, principals could sue their agents if any ESG is implemented without their explicit consent. In the case of captive principals, they could sue the individuals involved in the decision-making process. These individuals have a personal obligation to the insured collective. A lawsuit reminds them that their primary loyalty should be to the insured, and not to their own reputation or to managers and executives.

Scenarios

The diffusion of ESG into the investment world can play out in different ways. Three scenarios frame the various outcomes.

In the worst case, ESG is just another avenue for irresponsible risk-taking or even fraud. Paralleling, for example, the cases of the defaults or mortgage-backed securities, or financier Bernie Madoff’s fraudulent operation, once the broad market realizes the problematic nature of the schemes – the absence of methodologies, the arbitrariness in investment decisions – principals will lose their money.

In the best of cases, ESG has a positive impact. There is certainly room for socially conscious investing, as there are dedicated opportunities for impact-financing in sustainable development, the environment and climate. Also, maintaining good governance should be a concern for principals and agents anyway. But even in this scenario, in the absence of supervisory mechanisms, the principals still carry all the cost of the positive impact. It is doubtful whether they will also keep the rewards – it looks like managers and executives will reap at least some of the benefits without shouldering the drawbacks.

A third and more probable scenario would see principals take some of the above-mentioned actions to change their agents’ incentives. Currently, ESG is more popular with fund managers and financial executives than with their customers and clients. This calls for caution. Is it more likely that the financial sector has suddenly and completely changed its priorities, or that managers and executives have discovered a new source of income?

For the prudent investor, the answer is the latter. This makes this third scenario more probable than the other two. The unlikely association of managers and executives with left-wing activists and sections of the media to champion ESG is an even starker indication that agents are using it primarily for their own selfish motives: to generate income, to embellish their reputation, or both.

In the 1987 movie “Wall Street,” Gordon Gekko declares: “Greed, for the lack of a better word, is good.” Apparently, a better word has been found: ESG. It is synonymous with greed but sounds a whole lot better.