Europe’s misguided tax crusade

While the United States cuts taxes to spur growth, the European Union is blacklisting countries regarded as threats its fiscal system. The contrast speaks volumes about the economic priorities on both sides, and does not bode well for the long-term viability of Europe’s welfare states.

In a nutshell

- U.S. tax policy prioritizes economic growth, while Europe’s seeks to protect revenue

- To preserve costly welfare states, the EU must prevent internal tax competition

- The EU can enforce fiscal compliance, but it will prove to be a pyrrhic victory

At the end of 2017, there were two important events in the world of taxation. With a view to making American companies more competitive, President Donald Trump kept his electoral promise and cut taxes on corporate profits significantly. And with a view to preventing the rest of the world from outcompeting European producers, the European Union served notice that it would renew and intensify its fight against tax evasion (violations of tax laws), tax avoidance (exploiting loopholes in the tax legislation) and unfair tax competition.

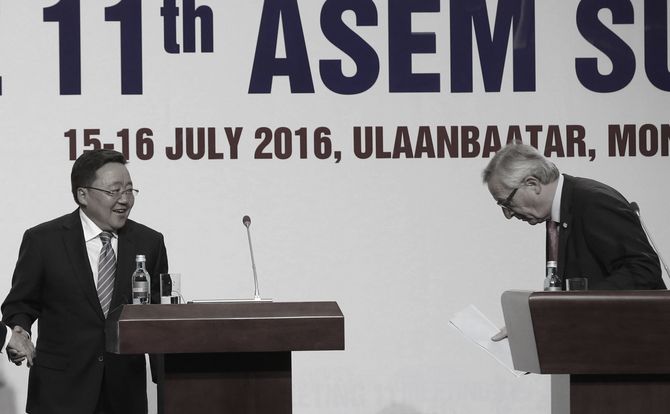

To that end, the European Commission prepared a blacklist of 17 countries. According to the Commission, each of these countries represents a serious threat to fiscal and commercial order worldwide. The list includes South Korea, Mongolia, Tunisia, the United Arab Emirates and smaller states such as St. Lucia and Samoa; it excludes EU members themselves.

Divergent approaches

The principles informing the American and EU approaches to taxation are clear. According to the current U.S. administration, the best way of solving economic problems is growth. High rates of economic growth make public expenditure sustainable, keep unemployment low, eliminate the need for monetary somersaults to stimulate demand, and ultimately serve to defuse social tensions. In this light, by reducing the tax burden, President Trump showed the way to encourage entrepreneurship and create wealth.

The EU’s take is manifestly different. From the European perspective, the main policy goal is to avoid cuts in the public expenditure necessary to maintain a large welfare state and engage in redistribution. Thus, tax revenue must stay high and possibly rise.

Downsizing the role of government does not rank very high on European political agendas.

Growth is important because it creates more revenue, allowing more spending and more redistribution. It also allows governments to sustain larger amounts of public debt. Yet while economic growth is acknowledged to be the key to higher living standards for the entire community, achieving high rates of growth is not considered important enough to justify the required structural changes. Downsizing the role of government does not rank very high on most European political agendas.

A simple question

On second thought, however, it is hard to believe that those 17 countries could present a serious threat to any EU policy, no matter how bad the policies might be. Growth has recently picked up in Europe as well, and economic forecasts admit some optimism.

If so, why has the European Commission reverted to its focus on tax evasion and tax avoidance, targeting a handful of harmless countries, when it could simply relax and enjoy the expanding tax base that economic growth delivers? It is theoretically possible for a company with substantial operations in France to set up its headquarters in, say, Ulan Bator and demand that Paris and Brussels respect Mongolian tax rules. Yet that would not deter the national tax authorities and the EU from extracting taxes and possible fines from the offender, even without a tax treaty with Mongolia.

The simple answer is that the European Commission does not believe that Mongolia, Tunisia or Samoa are fearsome competitors that will soon attract swarms of European companies seeking tax havens. The real purpose of this EU tax crusade, we would suggest, is to keep some of its member countries – for example, Malta, Ireland and the Netherlands – in line.

Faster growth and more optimism about the future have encouraged entrepreneurs to expand their businesses and contemplate more ambitious investments. The size of this pie amounts to trillions of euros, and many countries want a slice. EU members are no exception.

Now that entrepreneurial spirits are stirring, countries and regions hostile to entrepreneurship stand to lose out. If some EU countries were to take this opportunity to follow in President Trump’s footsteps, the EU’s own cherished project – which emphasizes a more centralized vision of economic policymaking at all levels, along with a unique tax strategy that nurtures a large welfare state and rampant state intervention – would be doomed.

Foolish pride

With this in mind, the European Commission has chosen to act preemptively. Its priority is to enforce discipline within its own ranks, while reminding EU members about their duty to enforce tax compliance, to resist the temptation to engage in a race to the bottom (tax competition), and to punish those who do.

The renewed efforts to combat low-tax regimes are thus not directed at tax havens, but at those who might disrupt the tax cartel already operating in Europe today.

The European Commission will probably succeed in enforcing fiscal discipline – and foolishly feel proud about it.

If this assessment is accurate, should we expect growing tensions within the EU, as some countries resist the strategy imposed by Brussels?

In the short run, the Commission will probably succeed in enforcing fiscal discipline within the EU bloc – and foolishly feel proud about it. For this to happen, however, two conditions must be met.

First, economic growth must remain satisfactory, so that enough tax revenue flows into government coffers to prevent anybody from questioning the current tax regime. Second, the gap between global and EU economic growth rates must not become too glaring, so that high taxation is not blamed for scaring away too many investors.

In the long term, the outlook could be considerably darker. Europe may have reason to brag about the sharpness of its fiscal claws. But the excessive tax burden will only help kill growth, while other parts of the world keep forging ahead.