The challenges of EU-China decoupling

Like the United States, the European Union faces the prospect of a systemic conflict with Beijing. However, an EU-China economic decoupling would pose significant challenges. Many countries on the continent, Germany foremost among them, are dependent on Chinese trade.

In a nutshell

- The pandemic has revealed the EU’s dependence on China

- Alignment with Beijing poses serious security risks

- The EU could seek a strategic alternative to a decoupling with China

In recent years, the European Union has gradually become more critical of China’s policies. Hopes for the long-awaited EU-China Comprehensive Agreement on Investment, in negotiations since 2013, have been dampened. Beijing’s call for ever-more discussions is thought to be a stalling tactic. A recent EU-China summit did not produce any substantial results.

By March 2019, one year before the pandemic, the European Commission had already downgraded China from a “strategic partner” to a “negotiating partner” and “economic competitor,” even a “systemic rival.” Beijing is now broadly believed to be undermining the EU’s global foreign, security and economic interests – as well as its promotion of democratic values and the rule of law. During the same year, French President Emmanuel Macron and high-ranking representatives of the European Commission declared an end to the period of “European naivete.” The Federation of German Industries has called for a more assertive and cohesive strategic policy toward China.

The 2020 pandemic deeply affected EU-China relations. Beijing was cast in an unflattering light after it launched a worldwide disinformation campaign around the origins of the virus. It also skillfully exploited faltering EU solidarity through “mask diplomacy,” by sending experts and medical supplies to Italy, Serbia and other European countries. Later, it emerged that Chinese medical gear was often defective and had not been donated by Beijing but in fact purchased by Italy and other European countries.

The disruption of global supply chains has not only affected the health sector, but also the automotive industry.

Moreover, the coronavirus has exposed Europe’s economic overreliance on China. The disruption of global supply chains has not only affected the health sector, but also the automotive industry and electronics manufacturers, among others. As a result, the EU plans to relocate some production capabilities for critical medical supplies and basic medicines to Europe.

A recent survey revealed that only 7 percent of Europeans perceived China as a useful ally during the pandemic, whereas 62 percent view China in a negative light. When the Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi toured through five European countries (Italy, the Netherlands, Norway, France and Germany) ahead of the planned Leipzig summit, both sides were disappointed.

By implementing its new security law in Hong Kong, Beijing disregarded international law and the Sino-British Joint Declaration of 1984. The agreement guaranteed Hong Kong a high level of political autonomy and democracy until 2047. After its implementation, the EU (including Germany) gradually became more critical toward the Chinese Communist Party. But the Merkel government has been accused of kowtowing and conducting an “automobile foreign policy” toward Beijing.

The technology race between the U. S. and China influences Brussels’ attempt to mitigate its supply-chain vulnerabilities. U.S. President Donald Trump’s decoupling strategy is a major challenge for the EU, which is unwilling to side with either party. European governments and the European Commission have called for a “Sinatra Doctrine” that would allow for a third way.

Strategic alignment

China is too large, too powerful and too sophisticated for Europe to consider emulating the U.S.’s formula for reducing economic dependence on it. All European governments are wary of disrupting their commercial ties to China for fear of economic repercussions. The European Court of Auditors recently stated that 15 EU member states had breached the bloc’s rules by concluding bilateral deals with China as part of the Belt and Road Initiative. These states have violated a 1974 Council decision that requires governments to inform the European Commission of economic or industrial “cooperating agreements” with third countries.

The technology cooperation between European and Chinese companies, universities and research centers has significant commercial and academic benefits. Technology supply chains are deeply intertwined. For German industry, China is no longer just an important production location, it has become a major research partner in digitization and artificial intelligence (AI). A technology decoupling from China would be more costly for Europe than for the U.S.

Facts & figures

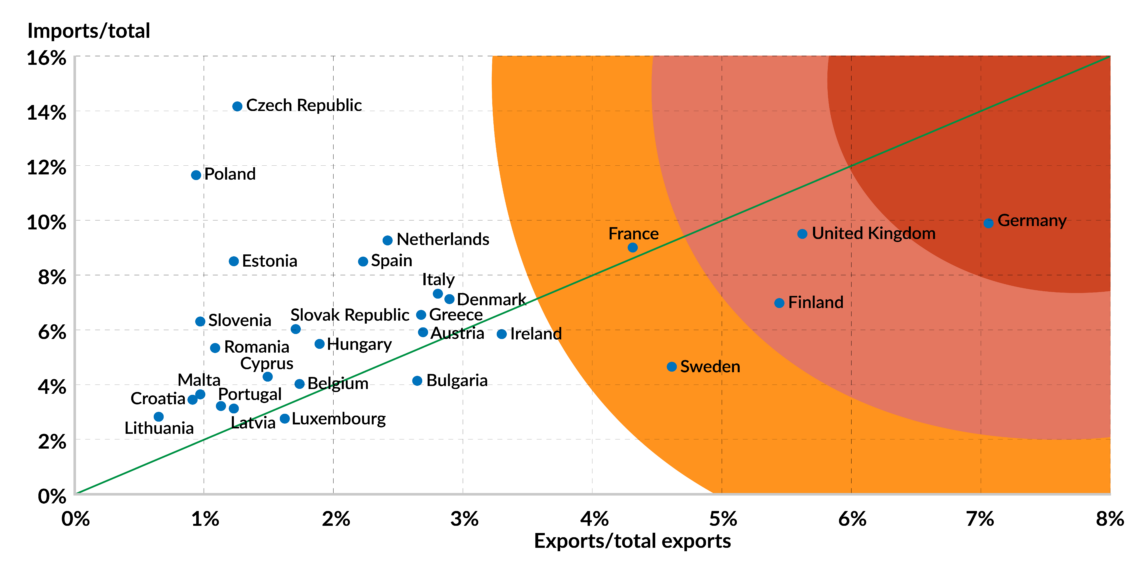

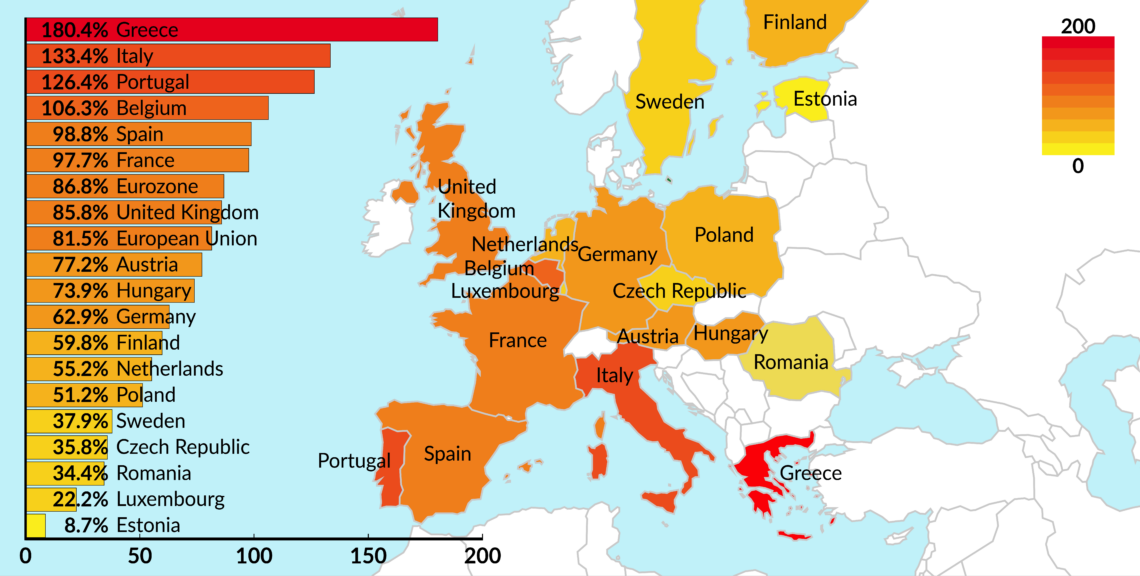

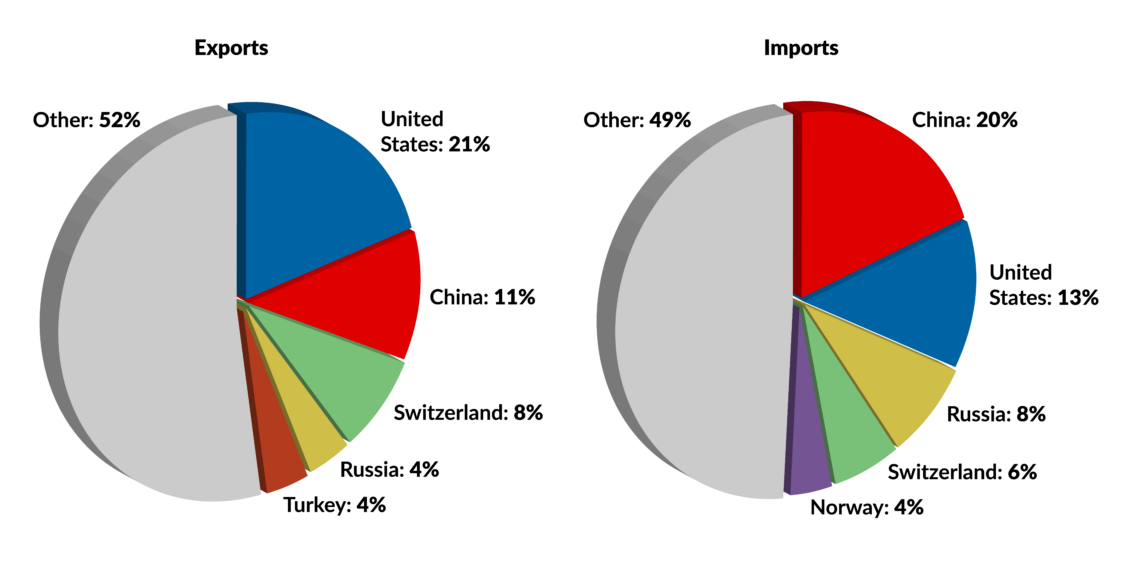

Both Berlin and Brussels are alarmed by the U.S.-Chinese bid to reach technological self-sufficiency. In 2019, EU trade with China amounted to 199 billion euros (representing 6 percent growth since 2017). German investments in China went from 30 billion euros in 2010 to 81 billion euros in 2017. Germany and Europe will have to balance economic imperatives and security interests.

Skeptics suggest that despite the EU’s growing interest in developing digital and AI technology, it may already be too late to catch up with Chinese – or American – progress. In other words, if you cannot beat China, join it.

This would entail more “preemptive obedience” and self-censorship toward China and lead to the expansion of Chinese political influence in Europe. The likeliness of this occurring would increase if the EU faces more economic problems in the future.

EU – China Decoupling

Globalization has increased economic interdependence by stretching supply chains across the world. But this interdependence does not mean geopolitical rivalries no longer exist. The EU in general and the Merkel government in particular have been slow in realizing the challenges China poses from this perspective. Berlin had hoped that the West’s growing ties with China would ultimately transform its political system into a Western-style democracy. But this German narrative, taken from its own Soviet-era integration policies, has not materialized.

Commercial interests and national security requirements have become more difficult to disentangle, making a decoupling from China much more challenging for the EU.

Europe is becoming more aware of the wider systemic competition and strategic rivalry emerging. Commercial interests and national security requirements have become more difficult to disentangle, making a decoupling from China much more challenging for the EU. Since almost all AI technologies are developed by civilian industries, the military has to collaborate with private companies to cope with these new digital and cybersecurity threats. The situation has created unprecedented challenges: essentially all emerging technologies are of a dual-use nature. China’s “military-civil fusion” strategy seeks to systematically exploit new developments for both civilian and military use. In response, the U.S. and other Western universities and research centers have begun to cut ties with Chinese telecom companies such as Huawei and ZTE.

Sinatra Doctrine

China’s trade and investment practices have endangered EU interests in Europe and beyond. Despite the deeply intertwined supply chains, the EU cannot ignore Beijing’s new belligerent “wolf warrior” diplomacy or the increasing cybersecurity risks caused by involving Huawei and other Chinese telecom companies. President of the European Council Charles Michel has recently stated: “Europe needs to be a player, not to be just a playing field.”

Europe is caught between U.S. and Chinese pressure because it cannot unite around a third way. It does not have its own competitive AI and high-tech digital industries. It is U.S. tech giants (Google/Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, Apple and Facebook) and their Chinese counterparts (Baidu, Alibaba, Tencent, Huawei and ZTE) that are the “gatekeepers to the internet” thanks to their unprecedented volumes of data gathered from billions of users. The EU is only beginning to stand up for its interests. It now seeks to defend its technological and digital sovereignty from Beijing’s state-backed enterprises, while restricting foreign access to its own markets as China does.

Facts & figures

Germany’s new policy guidelines for the Indo-Pacific region outlines a third way. The strategy emphasizes multilateralism and a rule-based international order but also attempts to enhance regional security cooperation and diversification of regional trade. However, it is unclear if those objectives will be met. Much depends on German EU leadership, and on the general willingness to pursue common European projects in the Indo-Pacific. It is becoming clear that the bloc can no longer rely exclusively on traditional soft power instruments without any hard power to defend its interests, as even Chinese commentators have highlighted.

Scenarios

The most likely short-term script, given the level of economic dependence and the lack of an EU-wide policy toward Beijing, might be a combination of alignment with China and a third way strategy. This would allow Europe to reconfigure some of its critical global supply chains without giving up its global interests.

The EU hopes to become a strategic and economic competitor for China and the U.S. by encouraging investment into its digital and AI industries and by protecting its high-tech industry. But in the mid- to longer-term, an increasing decoupling from China appears inevitable. The security issues tied to new technology developments cannot be disentangled from economic cooperation.

In the growing clash of systems between Western democracies and authoritarian governments like China and Russia, the EU will have to pick a side – at least in the mid-term perspective. In these circumstances, more transatlantic cooperation would be in the interest of both Europe and the U.S. However, Washington will have to take European realities into account if it wants to effectively impleme a broader Western policy toward Beijing.