The Chinese challenge and Europe’s dithering

The tensions between U.S. and China open plenty of opportunities for the EU to cooperate with Beijing. At the same time, the U.S. administration is putting pressure on its allies. Choosing either side poses risks, but further procrastination brings dangers of its own.

In a nutshell

- China wants a closer economic partnership with Europe

- The U.S. wants Europe to join it in bringing China to heel

- Brussels would prefer to leave it up to member states

Over the past two decades, China has all but mesmerized the West. At first, the expanding Chinese market attracted waves of European and American companies in search of easy profits and low labor costs. Later, the growing strength of Chinese producers in important high-tech industries like telecommunications and artificial intelligence was perceived as a harbinger of the West’s impending decline in lucrative and strategically critical sectors.

Not surprisingly, the two major Western players – the United States and the European Union – have reacted differently to the challenge due to their economic conditions, their historical backgrounds and the nature of their leaders.

The American superpower fears that its role as the dominant global performer is in jeopardy. It believes that China is free riding on U.S. technology and trade openness, and that it should therefore be punished accordingly. Indeed, the trade war unleashed by U.S. President Donald Trump is less a crusade for “fair trade” than an effort to keep China in check, both economically and geopolitically. The upshot is that while the Chinese have been making headlines for their supposed technological prowess, the Trump administration has tried to show the world that the U.S. is the only bulwark against Chinese supremacy.

The trade war unleashed by U.S. President Donald Trump is less a crusade for ‘fair trade’ than an effort to keep China in check.

So far, the outcome has been mixed. That Beijing has decided to keep a low profile during the trade dispute is not necessarily a sign of weakness. China’s economic slowdown is less dramatic than had been anticipated, while its ties with Russia have strengthened, for example in the energy sector. On the other hand, U.S. allies have not always appreciated Mr. Trump’s aggressive approach: most are comfortable dealing with Chinese companies and welcome Chinese investments.

Confused response

While Washington’s reaction to the challenge from the Chinese has been firm, Europe’s response has been confused: poor leadership and varying geopolitical views among the member countries are the main reason. If Europe continues to send mixed messages, it will miss out on economic opportunities and feed tensions, both with China and the U.S.

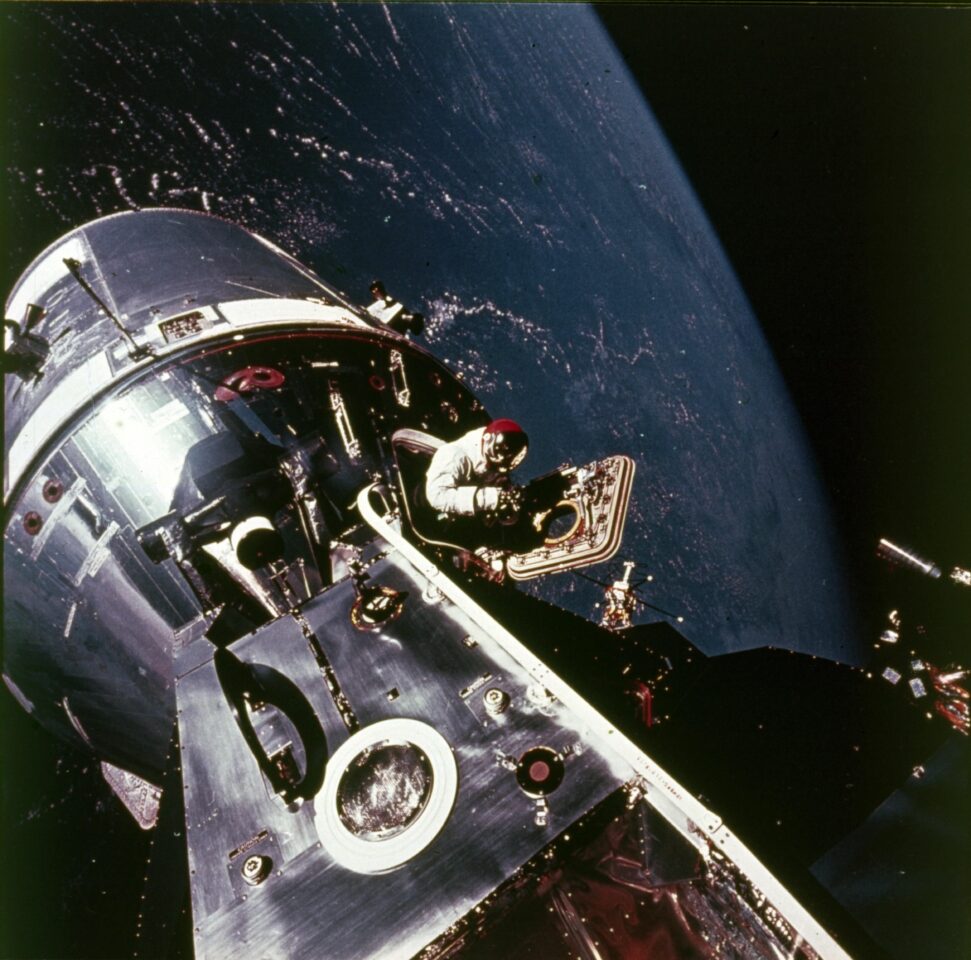

In theory, a European strategy should be based on its beliefs about Chinese technological capacities. Some 60 years ago, many Western observers were convinced that the Soviet Union was about to become the world’s technology leader, with clear military repercussions. It took the Americans a decade to persuade the world otherwise.

The U.S. space projects of the 1960s made a huge impression on public opinion and massive public investments into those programs played an important role. However, the real lesson of that decade – one that we sometimes forget – was that free-market systems provide technological results superior to those of a centrally planned economy.

Facts & figures

In the U.S. and Europe, we see technological success, while in centrally planned systems, failures abound. A well-performing technological environment is one where scientists interact with entrepreneurs and engineers to transform bright insights into useful products and processes, and discard ideas that are unlikely to lead to promising developments outside of the labs. Competition and cooperation are the key ingredients, and the U.S. became great partly because it had them in abundance. The Soviet bloc was doomed because it lacked them.

Sensible strategy

A sensible European strategy therefore depends on how the Europeans judge the Chinese economic system in perspective (rather than solely on its current performance) and its chances to promote innovation in high-tech industries. The answer is not obvious, and yet the issue receives little debate. Despite the general image promoted by the media, Chinese pride and self-complacency might hide a less flattering reality.

There is little doubt that the Chinese government regards its technological potential and its foreign-currency reserves as principal geopolitical weapons when dealing with other countries and the EU. Beijing is saying that tight cooperation with China is the key to the future of trade and technology. It has shown its readiness to make resources available to ensure that collaboration turns into a set of long-term engagements (based on a wide range of joint investment projects, not only in infrastructure). These are persuasive arguments. But will China deliver? And at what cost? Europe has three options, from which different scenarios follow.

Committing to China

One option would be to commit to closer long-term economic ties with Beijing. This means that Brussels will fine-tune its regulatory frameworks and trade barriers so as not to harm Chinese exporters too much, encourage the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) and look at Chinese foreign direct investments with a more benevolent eye. The costs of such a strategy are not negligible. The Americans will not be happy and might retaliate in a variety of ways, regardless of the consequences for their interests.

The ubiquitous presence of government in the Chinese economy will prevent the development of viable technological growth.

For example, Washington might scale down its military presence in Europe, start extended trade disputes with the EU or perhaps introduce some kind of targeted regulation hitting European investments in the U.S. Moreover, they could open an entirely new front and set limits on European access to American technology. Would this path be worth it for Europe?

Probably not. Chinese companies are outstanding developers of existing technologies and possibly innovative pathbreakers in several areas. Yet, the ubiquitous presence of government in the economy will prevent the development of what is necessary to enhance viable technological growth: competition, interaction, unfettered exchange and cross-fertilization that only a vibrant market economy can deliver.

This is not to say that Europe is much better. Tying together one success story of the past (Europe) and one basket of partially empty promises (China) is unlikely to be a satisfactory recipe for a long-lasting, peaceful and fruitful partnership. And divorcing a disappointing technological partner could be very costly, as some highly indebted African countries are finding out.

Ignore the dragon

The second option for Europe would be to ignore the Chinese variant. This would also come at a price. Failure to cooperate with them today might put European companies at a disadvantage tomorrow. If the current tensions between Beijing and Washington subside, and if part of their deal were to include privileged treatment for American partners, Europe might be left behind.

Moreover, Europe’s reluctance to cooperate with China might send the wrong message to Moscow. It may be perceived as a sign of weakness and servility to the U.S – not the ideal starting point for developing a long-term partnership with Russia.

A hardline EU approach might raise problems for internal cohesion.

Finally, a hardline EU approach might raise problems for internal cohesion. Foreign policy has always been a weak spot for the bloc. Choices that involve economic geopolitical issues are likely to lead to situations in which Brussels takes a position that is soon made irrelevant or circumvented by at least some member countries. Further and perhaps more acute problems could arise if the European Commission were to take measures that contravene formal or informal agreements already sealed by member countries.

Weak compromise

Can the EU extract itself from this dilemma or find room for compromise? The obvious solution would be for Europe to acquire credibility at home and technological bargaining power on a global scale. This, however, will not happen any time soon.

The charisma and the road map of Europe’s leaders are not overly impressive. Their efforts to acquire credibility through ever-greater regulation and paperwork scares risk-taking entrepreneurs. The current mix of subsidies to shrewd applicants supported by wily consultants, with sanctions on thriving businesses is unlikely to take Europe very far.

The third option, compromise, seems the most likely but will make nobody happy. Presumably, Brussels will let each member country have its way with China, decline to decide on an overall strategy and try to ease tension with the U.S. by grand pronouncements in favor of Western values and loyalties.

In doing so, however, the EU authorities might further dilute Europe’s geopolitical role, create more disputes with Washington and hinder its ability to be a global economic actor in the east. That could hurt its relations with China, and possibly with Russia and India in the future.