Failed experiments in EU foreign policy

While many are quick to blame excessive nationalism for the EU failure to come up with a unified foreign policy, the situation is more complex. Proponents of centralization will likely need to adopt a more realistic approach, lest the union become even more fractured.

In a nutshell

- The EU has long struggled to unify its foreign policy – to no avail

- Member states struggle to give up economic interests for the sake of integration

- With

The proponents of an ever closer union of European states regularly struggle to answer a simple question: why does the European Union not fulfill one of the fundamental tasks of a confederation, namely to jointly ensure the security of its members and their external representation?

Push for centralization

A first effort to coordinate European foreign and defense policy at the supranational level failed in 1954 because of France, which categorically refused to give up its sovereign rights. A counter-proposal submitted by Charles De Gaulle in 1960 envisaged a “Europe of the Fatherlands,” with more political, cultural and military integration through increased collaboration between governments instead of supranational governance. The plan was put aside because of the resistance of those who wanted the “completion, deepening and enlargement” of the Treaty of Rome.

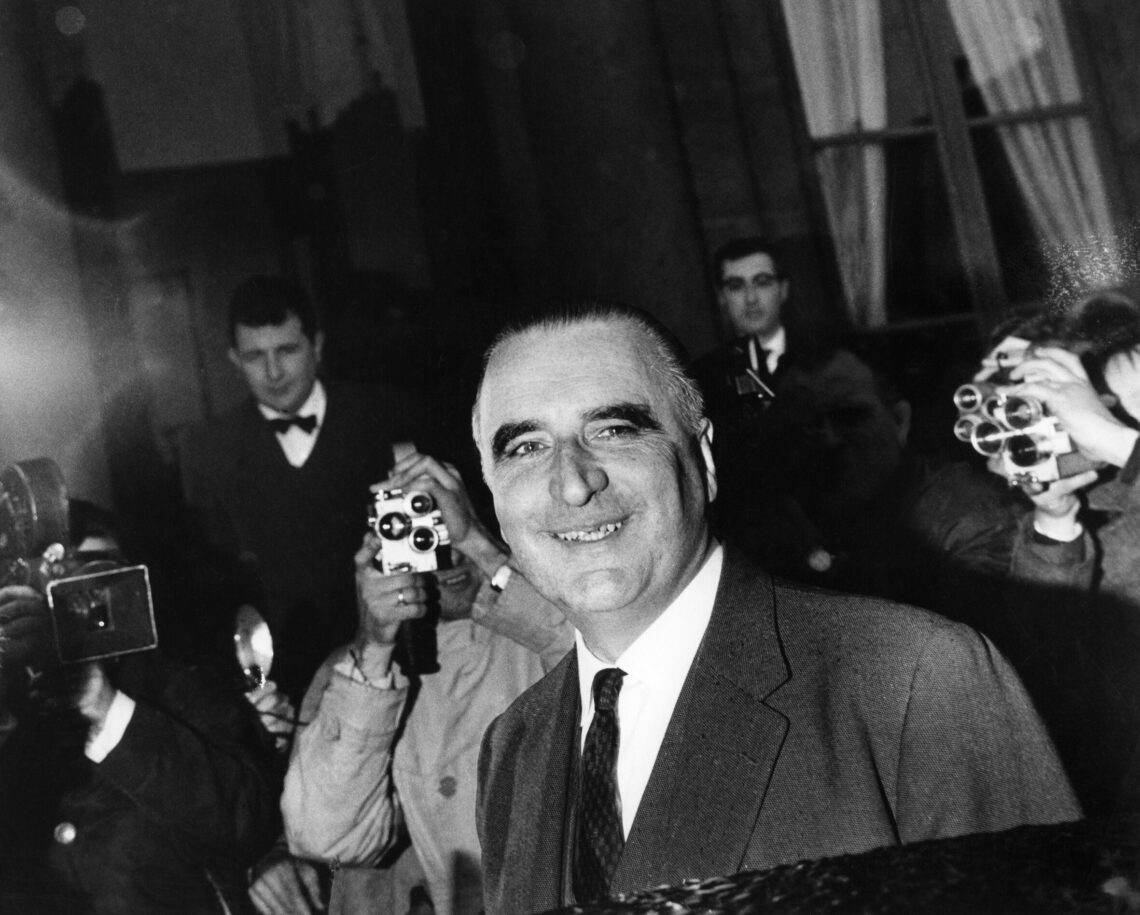

The resulting crisis was only defused after De Gaulle’s death, under his successor President Georges Pompidou. In 1969, it was decided at the Hague Summit to formalize the political power of the European community. The following year, the European Political Co-operation (EPC), meant to create a coordinated EU foreign policy, came into force. It did not, however, grant the European Commission or the European Parliament any competences.

Foreign policy priorities vary not because of nationalism, but because of diverging geopolitical and economic interests.

The turning point, which liberal Eurosceptics see as the fall from grace in European unification, came with the Maastricht Treaty in 1992. The Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) was established as one of the “three pillars” of the EU in addition to the economic and monetary union as well as police and judicial cooperation.

The inability of the member states to find a common response to dangerous crises close to home rapidly became glaringly obvious. While Germany supported Croatia’s right to self-determination during the war in Yugoslavia, the United Kingdom and France implicitly sided with Serbia by considering the Yugoslav federation legitimate even after the Croatian declaration of independence. The fundamental error of the Maastricht Treaty is the assumption that conflicts of interest can be overcome if nation states are given a supranational corset. This mistaken assumption also underlies the CFSP and the common currency. It does not take into account, for example, that Lisbon and Athens naturally have an attitude to Russia that greatly differs from that of Vilnius and Warsaw. The former colonial powers, France, the U.K., Italy and Spain, have more ties to the Middle East, Africa and Asia than Germany does. But in turn, Berlin works more closely with the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.

Diverging priorities

Foreign and security policy priorities vary not because of nationalism, but because of diverging geopolitical and economic interests, as well as historical and cultural background. During the war in Yugoslavia, the invasion of Iraq, the Arab Spring, the intervention in Libya and the war in Syria, France, England, Italy and Germany found themselves on different sides, and none of these countries had nationalist parties in government.

Henry Kissinger’s legendary “Who do I call if I want to call Europe?” was not answered by the CFSP. Even three decades after Maastricht and a year and a half after Brexit, the EU is not seen as a homogeneous bloc in Washington, Moscow and Beijing, but as a large network bound by more intergovernmental cooperation than in other parts of the world. The U.S., Russia and China do take into account the statements of the High Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy – but only after ascertaining how things stand in Berlin, Paris and other European capitals.

The principle of subsidiarity, so often invoked and so often disregarded in the EU, should also apply in the field of foreign policy. Agreements between two or more EU countries, or individual member states with countries outside the Union, are often better suited to complex, dynamic realities. This has become apparent again in the crisis surrounding Europe’s vaccine rollout.

Western Europe’s homogenization efforts always met resistance.

The drive to forgo bilateral relations and look for a “European solution” is decreasing. Centralists will need to come to terms with this reality whether they want it or not, if only because their ability to keep member countries on a leash is diminishing. The EU discourse has become defensive; Brussels now mostly tries to safeguard whatever centralization has already been achieved.

EU centralists argue that European states can only defend themselves against external threats by joining forces – an old argument. There have been several attempts to place the continent under one authority. In Carolingian Europe, Charlemagne had set himself the goal of restoring the Roman Empire and confronted the Eastern Roman empire of Byzantium. In the East and south of the Alps he was considered a barbaric usurper. In the West he was canonized three and a half centuries after his death.

The myth of Charlemagne as the father of Europe inspired Napoleon in his attempt to subordinate the continent. Even Nazis and fascists pursued unification. Western Europe’s hegemonic homogenization efforts always met resistance. Napoleon’s revolutionary expansionism, Hitler’s racist imperialism and Stalin’s Sovietization produced violent national counter-movements.

Now too, centralization and homogenization in the EU are reactivating national awareness. At a time when the EU is looking to expand in south-eastern Europe, migration and the euro are exacerbating conflicts between its northern and southern member states. Charlemagne’s legacy is no longer an inspiration, but a burden.

European nations did unite of their own free will whenever they had to fight a common enemy. They fought against Arab and Ottoman expansionism, against revolutionary France, against National Socialist Germany and against the Soviet Union. Most recently, NATO served as protection against Moscow, which could only be kept in check by joint efforts.

New risks

The threat picture has changed since the collapse of the Soviet Union. Although eastern EU member states still feel threatened by Russia, Western Europe no longer does. In Berlin and Paris, even the illegal annexation of Crimea and the aggression against Ukraine were not viewed as a permanent impediment to relations with Moscow. Germany is sticking with the construction of the Nord Stream 2 pipeline regardless of opposition from its eastern neighbors, and against Washington’s explicit reservations.

European centralists are hoping for further initiatives from Berlin and Paris. But the “Franco-German locomotive” that was supposed to pull other countries along and promote integration has been rather quiet recently. In Germany, the Merkel era is coming to an end. The CDU’s electoral defeats in Baden-Württemberg and Rhineland-Palatinate suggest there could be a chancellor from the Greens for the first time. One can only speculate about the foreign and security policy effects of a possible left-wing coalition, but no European policy initiatives should be expected from Germany this year.

Like with Russia, the EU cannot agree on a common line toward Beijing.

Meanwhile, French President Emmanuel Macron used Ms. Merkel’s weak leadership in the EU, Brexit and Joe Biden’s victory to make his common security policy plan palatable to Europeans. He alludes to the Gaullist rhetoric, but strives for an even more centralized, French-led EU in a Europe that extends “from the Atlantic to the Urals.” Mr. Macron neither assumes nor excludes cooperation with the U.S. and NATO, but emphasizes the need to make Europe autonomous. The EU, says the French president, cannot rely on Washington in an emergency. He sparked controversy in Berlin when he remarked that NATO had become “brain dead” under U.S. President Donald Trump. The German Defense Minister Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer countered that the transatlantic alliance would remain a pillar of her country’s security policy.

Outlook

In March 2021, British Prime Minister Boris Johnson presented the House of Commons with a comprehensive document on the foreign and security policy priorities for the next few years. It is the first fundamental redefinition of the UK’s global role since the end of the Cold War. Mr. Johnson reaffirmed his country’s commitment to NATO and Euro-Atlantic security, and stated that his country would remain ready to counter the threats emanating from Russia. But the geopolitical focus has shifted to the Asia-Pacific region, where China poses a growing risk to British interests. Accordingly, London wants to cooperate more intensively with Japan, South Korea, India and Australia. The British fleet will be enlarged and an aircraft carrier will be dispatched to the South China Sea. The number of nuclear warheads is to be increased from 180 to 260.

Ms. Merkel, Mr. Macron and Mr. Johnson’s behavior toward President Biden is somewhat reminiscent of Noah’s sons, who cover their father’s nakedness. The decline of the U.S. and the rise of China dominate international security today, overshadowing all other conflicts. And, like with Russia, the EU cannot agree on a common line toward Beijing. Torn between economic interests and fears of Chinese hegemony, the EU stares as if spellbound at the worsening conflict between Beijing and Washington. The world is losing Europe, but it does not look as if the world will notice.