The EU’s future: Like Switzerland or more like Italy?

The drive to transfer ever more sovereignty from diverse member states to Brussels is turning the European Union into an inefficient, centralized nation-state construct.

In a nutshell

- EU creators sought to curb nation-states’ destructive potential

- European supranational empires of old offer valuable guidelines

- Instead of a confederation, Brussels is pushing toward a large nation-state

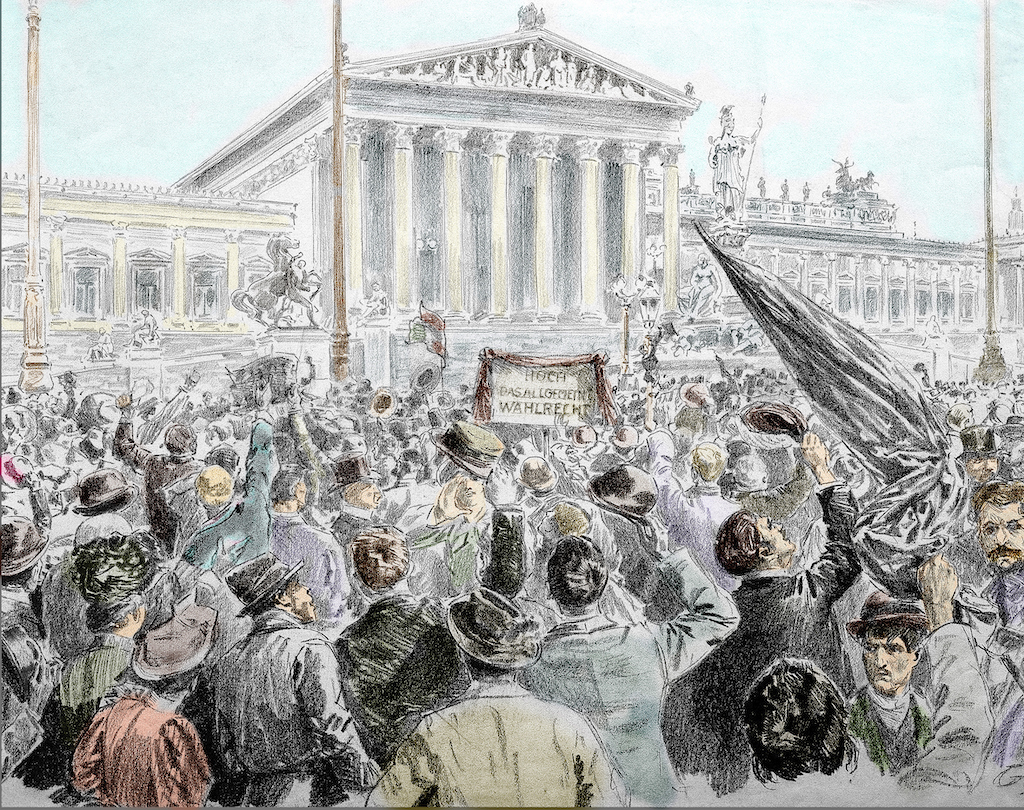

Critics of the European Union often deem it to be an imperialist project. Its founding fathers, who lived through two world wars, were indeed wary of the effects of unleashing nationalist ideas in the old continent. Firsthand experience made them seek institutions that resembled the old supranational empires, which allowed, at least potentially, for the coexistence of different national groups. Hence, instead of unfettered sovereignty for nation-states, they labored for the post-World War II international order to be a rules-based system transcending national boundaries. The hope was that it would curb nation-states’ destructive and protectionist potential.

None had seen the issue more clearly than English historian and politician Lord Acton (1834-1902). In an 1862 essay, he prophesied the totalitarian potential of nationalism. He maintained that a single national group associated with a single government was the most subversive and arbitrary of all political ideas, even more so than socialism. The modern theory of nationality held that such a setup was bound to generate conflicts, he insisted. Lord Acton argued that “the co-existence of several nations under the same State is a test, as well as the best security of its freedom.”

Allure of the nation-state

Long criticized as remnants of a pompous past, supranational empires have become an object of longing after nationalism swepd Europe in two world wars. So, in a sense, the EU founders had in mind something that resembled old empires, though updated to be reconciled with democratic politics.

However, supporters of the EU tend to be leery of placing it in the same box as empires of the past. The union’s architecture is a stratification of treaties that are difficult to disentangle; Brexit showed that. For the most part, European institutions are not the result of a top-down design but the coming together of competing interests and national diplomacy. They have not sprung off the head of Zeus but have been the result of a piecemeal process and of countless compromises, most of which left this or that set of nation-states less than fully happy.

It promises the resolution of conflicts by going for a single control room in society.

And this is not a gripping narrative, particularly in times like ours, in which political ideas aggressively compete for attention. One needs bigger and bolder claims to impress one’s audience. On top of that, a narrative that focuses on a step-by-step process (and often two steps forward and one backward) naturally tainted with compromise is at odds with our most deep-seated ideas about politics.

In the modern era, the nation-state has been the most successful of political institutions, digging the grave of supranational empires and smaller political units because of its claim to monopoly. It promises the resolution of conflicts by going for a single control room in society, trading diversity for unity and pluralism for stability so successfully that we can hardly think of using other categories in discussing its legitimacy.

The diehard integration enthusiasts call for an “ever closer union.” They do not seem to consider the EU an institution (or, more precisely, a set of institutions) inherently different from nation-states as we know them, but instead as a large nation-state. The dream is that of a “federal” Europe, yet not in the sense of a federal, pluralistic, perhaps even dynamic arrangement. The federalism which the europhile dreams of is a process that leads from diversity to a single unit – out of many, one, as in the motto of the United States.

A confederative model

Hence the idea that the EU should replicate the sort of powers nation-states used to possess. The notion is best epitomized by the rather strange locution “sovereignty transfer.” Sovereignty, which implies the ultimate authority in decision-making, is accounted for like a cake to be sliced, and the slices can be moved from Paris and Rome to Brussels. Once enough pieces are transferred to Brussels, the conventional wisdom goes, we will have something resembling the cake we originally started with but bigger, as slices will have come through from all over the continent.

A confederative model for Europe was not a fantasy, and it resembled what we had and wanted to have for a long time. The founders thought of a supranational space in which no nationality could easily overcome the others, and all would learn to live in peace. However, that implied a pragmatic sorting out of those public goods that could be supplied at the European level versus those that should be provided by member states or at the lower level of government. In the European jargon, this came to be known as the principle of subsidiarity, a concept borrowed from Catholic social doctrine stipulating that political matters ought to be handled by the competent authority closer to the people affected by them.

The current logic assumes that Brussels should become more powerful while Rome, Berlin and Paris less so.

If the principle of subsidiarity were to be followed strictly, the EU’s 27 member states would aim to become like a larger Switzerland with its 26 cantons. The issue here is not the powers Brussels currently enjoys. The Swiss confederation is a more compact political body than the EU, and Bern is more powerful in its relation to the historic canton of Appenzell than Brussels is to Berlin.

Yet the logic behind the confederation is that a range of powers and responsibilities are clearly and openly delegated “up” to the higher level of government: something which, to be fair, could also bring about changes within the boundaries of nation-states, such as devolving some responsibilities “up” may nudge to devolve others “down.” In its short-lived secessionist phase, the Italian Northern League (the political party now known as Lega) proposed something like this arrangement.

Creeping power grab

The current logic is, however, different. It assumes that Brussels should become more powerful while Rome, Berlin and Paris less so. The idea does not fit a clear and well-defined list of functions that are best left to European institutions. Instead, europhiles tend to look for opportunities that might allow them to give carte blanche to Brussels, albeit beginning with apparently limited endeavors. Hence, the EU is supposed to grow through crises and thanks to crises: whatever the problem or issue, it could foster a slice of national sovereignty to be cut and brought up to a higher level.

Behind this, there is an overarching belief in the higher efficiency of centralization, which is perhaps the true landmark of modern politics. Politicians trust themselves more than the taxpayers; they seek a single control room, and the more it controls, the better. This approach fits well with a protectionist outlook of economics, which sees Europe (“fortress Europe,” as some say) as one trading bloc set to countervail others (the U.S., China). In this perspective, the EU is a bigger version of France – philosopher Anthony de Jasay calls this approach “the Europe of Colbert,” not by chance.

A European national identity seems to be surrogated by an appeal to shared political values.

There are many problems with this, but two of them stand out. The first one concerns the issue of identity. Certainly, Europe is not short on identity, but being a European is a matter of culture and, as such, it suits civil society better than any political project. Nationalities, no matter how artificial, were used to cement nation-states as they appealed to all classes in society and bound them together in a sometimes perverse but certainly efficacious sense of unity. Similar sentiments are difficult to evoke at the EU level because the EU precisely lacks the raw material nation-states used in the past: a common language, for a start. So far, a European national identity seems to be surrogated by an appeal to shared political values: a version of “constitutional patriotism” in a political framework where the Lisbon Treaty plays a surrogate to a proper constitution.

Scenarios

The second problem is that if the design is unitary and aims to make Europe look like a single nation-state, the process remains a step-by-step advance. Were the aims limited and a confederation the ultimate goal, this would work nicely. But since the idea is to go for a bigger nation-state, the method looks at odds with the object. The ambition is to find different tipping points, search for subterfuges, and build levers that eventually would reach the actual goal.

The critical point is the consolidation of European public finance, which implies some level of international redistribution. A significant step forward was accomplished with Covid-19 and the so-called “NextGenerationEU” funds, sowing the seeds for an ever-closer union. Yet this creates conflicts, particularly between those member states that will be net beneficiaries and those that will be net payers. This can be seen in the tension between the northern and the southern European states. The first group is made up of social democracies, like the second. However, they have kept their budgets under control. Subsidizing more indebted states may be the price to pay for European unity but is perceived by many voters as unfair.

At the moment, Europe does not look like a bigger France in the making but a bigger Italy. This is the model of nation-state Brussels is inadvertently pursuing.

Italy transfers funds from its northern part to the south. The flows are not exceptional or meant to overcome some particular problems; they are regular and have brought minimal results thus far in fostering the Mezzogiorno’s (Italian south) development. Per capita income used to be half that of the north after World War II, and it is still half today. Tensions caused by this unevenness have been remarkably small. However, suppose those dynamics were introduced between the Dutch and the Portuguese or the Germans and the Italians. In such a case, political tensions would escalate rapidly.

Europe could become a bigger Switzerland if its leaders were not so bent on making it a bigger nation-state. What they aim for is a bigger France, but instead, they may wind up with a bigger Italy.