Europe’s risky recovery funds

The EU strategy towards Covid-19 recovery involves gigantic stimulus response programs. While financial support makes sense, these initiatives often lead to fraud and corruption. Recent reforms may not be enough to prevent a repeat of these negative consequences.

In a nutshell

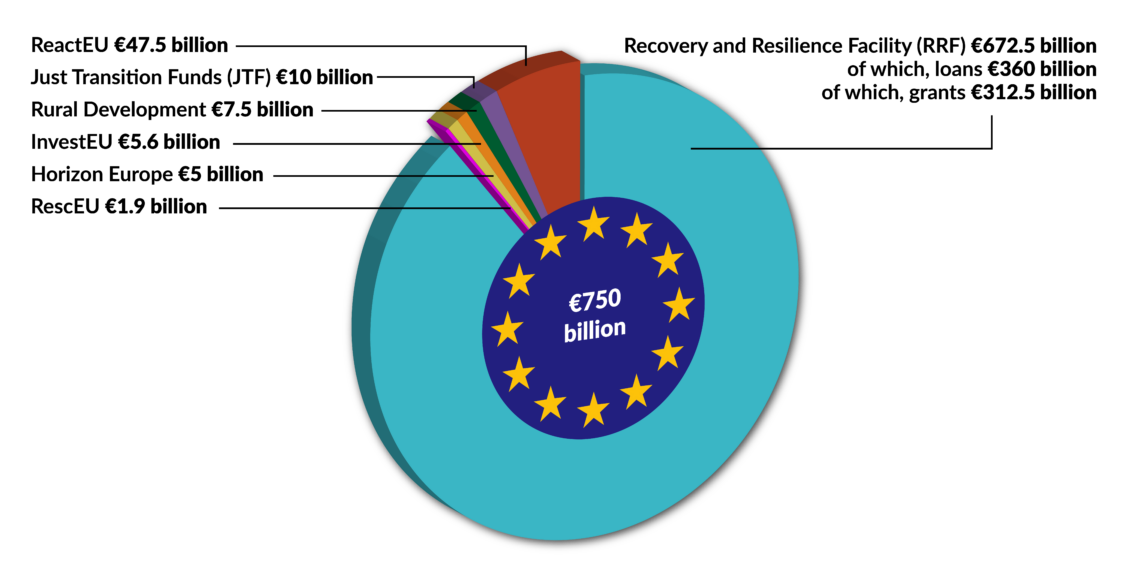

- The EU earmarked 750 billion euros as a Covid-19 stimulus response

- However, such funding tends to distort market competition

- It could also push Europe toward a planned economy

The Covid-19 crisis has created economic chaos and spurred a “stimulus response” from various governments to prevent a crash. Given the nature of the current shock, which hit supply first, the measures are targeting businesses and specific industries, especially with extra cash.

While most economists support such policies, many are also aware of their potential risks. The funding already provided, as well as broader economic history, offer some warnings for Europe in particular.

Last year, the European Union agreed on a 750 billion-euro stimulus package, based on newly issued debt. This Covid-19 recovery program began on January 1, 2021. It includes 360 billion euros in low interest loans and 312.5 billion in grants, with the rest doled out in other special initiatives. The money will be distributed in the first half of this year, after national governments each design a “recovery and resilience plan” that is approved by the European Commission (with each country allowed to inspect the others’).

More than a third of the funds must be spent on climate change mitigation, and a fifth on digitization. Two-thirds of the grant money will be disbursed in 2021 and 2022, according to three criteria: population, gross domestic product (GDP) per capita and the average unemployment rate over the five years preceding the outbreak. Plans can be submitted until April 30, 2021. As much as 10 percent of the funds assigned to the member states can be distributed before the investment projects are implemented.

Fraudsters rejoice

Given the huge amount of money, the first obvious risk is fraud. The Common Agricultural Policy has traditionally encouraged graft. Some of the most famous instances have involved Corsican cows, Greek olive trees and “Croatian sugar.” More recently, “oligarch farmers” in Hungary, the Czech Republic (a scandal involving Prime Minister Andrej Babis) and Bulgaria have hit the news. Ideally, subsidies should be conditioned on consistent, transparent rules. That is still not the case, despite recent improvements in several member states.

Most governments in Europe had already initiated a stimulus response and thrown money at the Covid-19 crisis before the historic deal. Greece, for example, released 1.14 billion euros of EU cohesion policy funds to some 90,000 small and medium-sized enterprises in July for projects on “competitiveness, entrepreneurship and innovation.” However, corruption is still a major issue in the country. Transparency International ranked it 60 out of 198 countries in 2019. In November 2020, the European Council’s GRECO (Group of States against Corruption) noted that the Greek authorities had not fully implemented eight out of its 19 recommendations for combating corruption. Measures to spend EU money are approved quickly – reforms much less so.

According to OLAF’s latest report, environmental fraud has been on the rise.

The European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) and the European Commission both produce annual reports on corruption, and these are not always encouraging. OLAF has a whole list of examples, from nonexistent projects, to money spent on private casinos, to inflated prices for both public and private projects. The most famous example is probably the Volkswagen subsidies from the European Investment Bank for an engine that instead of being more environmentally friendly, had technology that cheated emissions tests. Overall, in 2019, OLAF opened 223 investigations and recommended the recovery of 485 million euros.

Subsidy hunters

With the new European stimulus response, each national plan needs to be approved by the Commission, and other countries can also have a say. This seems like thorough oversight, and one hopes GRECO, OLAF and the Commission will effectively prevent fraud. But the other problem with subsidies is the fine line between fraud and abuse.

The large variety of national and European programs has brought about a new profession: subsidy hunters. Most large municipalities have teams dedicated to hunting subsidies for local projects. Obviously, lobbies for private interests have also developed such services. Given that more than a third of the funds will have to go to climate change mitigation projects, the chance is high that many companies will turn to “greenwashing” (presenting a project as more environmentally friendly than it really is) to attract subsidies. According to OLAF’s latest report, environmental fraud has been on the rise.

The frequency of fraud and abuse will greatly depend on whether authorities can counter these threats. In Europe, leaders count on devices such as the Early Detection and Exclusion System (EDES), which is supposed to protect the EU’s financial interests “against unreliable persons and entities by excluding them from participation in EU funds award procedures.”

Moreover, the European Public Prosecutor’s Office launched this autumn will have “the power to carry out criminal investigations and prosecutions,” which should help recover embezzled funds. These entities should be aided by the Whistleblower Directive, which member states must transpose into their national laws before the end of 2021. Still, given the magnitude of the new funding, it is worth wondering whether the new tools will suffice.

Rise of the zombies

Besides the obvious short-term risks, there are other, less visible, longer-term pitfalls. The subsidy process can, for instance, lead to a “zombification” of the economy. European Central Bank President Christine Lagarde noted in a speech in November that “concerns about ‘zombification’ or impeding creative destruction are misplaced.” But some observers beg to differ. Such stimulus response policies can allow stagnant firms struggling to repay their debts, with poor prospects for future growth, to prolong their zombie-like existence, notably thanks to low interest rates.

According to research conducted by the Bank of International Settlements before the outbreak of the Covid-19 pandemic, the number of zombie firms has been rising since the 1980s: from 2 percent to 12 percent of all companies in 2010, with each economic downturn ratcheting up their ranks – later recovery did not lower this percentage. Since they are much less productive, zombie firms pull down the average productivity and innovation in the economy. They crowd out investment and human resources and prevent their allocation to better uses, in more dynamic firms.

While zombie firms protect some employment – a visible benefit – they are also a drag on the economy and therefore block other jobs from being created – an invisible but pernicious drawback. In times like these, with generous stimulus response programs doled out at such rates, these companies are under less pressure to reduce debt and restructure. Public decision makers want to avoid short-term unemployment at all costs. Nonviable businesses will actively lobby for more subsidies, invoking their allegedly beneficial economic role.

Shielding firms from bankruptcy will lead to an unofficial system of protection.

While public officials’ pursuit of short-term goals can be excused given the magnitude of the current crisis, in the mid- or longer-term perspective, the unfortunate effect of shielding firms from bankruptcy and restructuring will be the emergence of an unofficial system of protection and legal cronyism. Often government aid comes with strings attached. For example, Senior Aerospace, a French firm specializing in hi-tech components used in Airbus aircraft and Ariane rockets, received half a million euros in subsidies to bring its production from the Netherlands back to France (an investment of 1.5 million euros). While driven by good intentions, such reshoring operations can hinder the modern, efficient logistics of international value chains, increasing costs and prices.

Central management

Attaching such strings could gradually allow politicians and bureaucrats to create a form of centrally managed economy. While the pandemic emergency must be mitigated with a stimulus response in the short term, the risk remains that in the long term these new controls will stay in place. Crises spur the growth of bureaucracy and central regulation. Recovery never seems to reverse the process.

So even without fraud and abuse, these huge spending programs tend to distort prices and competition. The Common Agricultural Policy (which accounts for 40 percent of the EU budget) has distorted the market for years. In fact, the oversight systems put in place to make sure the funds are not used illegally could even justify more control and surveillance, and thus more distortions.

Centrally managed economies typically have two problems. The first is a lack of knowledge. Central planners do not have sufficient information to identify needs and address them properly (often called “picking winners”). The second is that bureaucrats have no incentives to perform well – they have no “skin in the game” – like investors do. Instead, they are playing with other people’s money. Not only do they lack any incentive to choose wisely, but they may also want to support projects that benefit them politically, rather than those that are most economically sound.

It is hard to see how the enormous amounts of government funding could not create a bubble of inefficient projects.

Taken together, these two problems raise the issue of accountability. The environmental sector is a good case in point. It is hard to see how the enormous amounts of government funding could not create a bubble of inefficient projects, crowding out better alternatives that do not necessarily meet EU criteria. While the environment is certainly an important cause, even mild forms of central planning and subsidies can end in catastrophe. They delay or prevent timely, smoother market corrections. The road to hell, as they say, is paved with good intentions.

Magic money

If another crisis over the misallocation of resources were to erupt, more lax monetary policy would be needed to soothe the pain. The fallout would be similar to that of the 2008 global financial crisis – a spiral of interventions to correct past mistakes that led to new ones.

Monetary policy in recent years both in Europe and the United States has pushed interest rates to historically low levels, allowing governments not to worry about market pressures on their debt. The expectation was that they would reform in the meantime. However, many failed to do so, planting the seeds of future situations that will “require” another stimulus mechanism – and bringing us even closer to a centrally managed economy.

Most stimulus spending is financed by unconventional monetary policy. A recent note from the Bank of France stated that more than 750 billion euros of debt issued between March and August 2020 in the European Union has been bought back by the Eurosystem: 59 percent of government debt and 63 percent of private debt. Banks and collective investment funds bought the rest, usually not to make a profit, but mostly to use it as collateral for central bank loans – also landing that debt on the ECB’s balance sheet.

Given the current context, there is no reason to think that the course of monetary policy will change soon. More and more people are calling on authorities to forgive debts taken on to weather the pandemic. The atmosphere does not bode well for fiscal transparency, accountability and sound reform. Even if pro-market forces in Europe resist the trend, the gradual rise of a centrally managed economy remains a possibility.