The pitfalls of adopting a European minimum wage rule

While designed to provide the poorest workers with a decent standard of living, the European Union approach is flawed and may lead to greater unemployment and higher costs.

In a nutshell

- The agreement calls for a national minimum wage in 21 of 27 EU countries

- It is set at 60 percent of the median or 50 percent of the average wage

- The rules are nonbinding, but may lead to further centralization in Europe

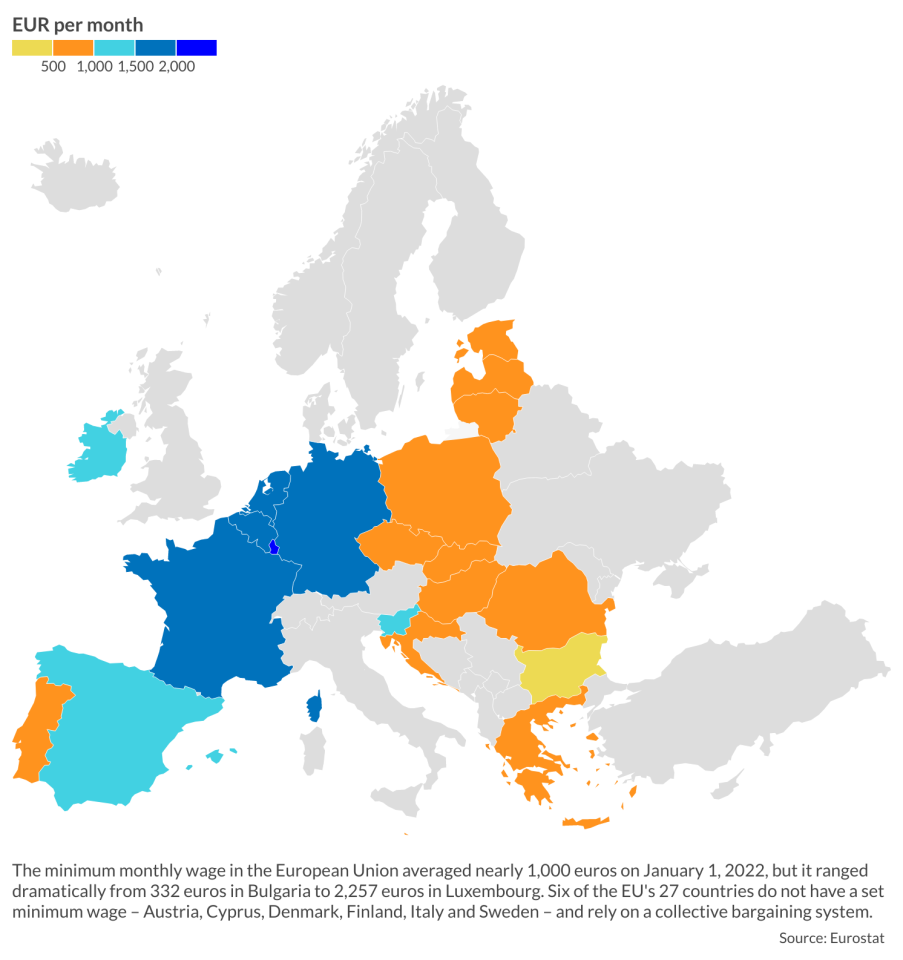

The European Union and the European Parliament reached an agreement in June on a common framework for rules to set the minimum wage in the 27 EU member states. Except for six countries that will keep their collective bargaining system (Austria, Cyprus, Denmark, Finland, Italy and Sweden), the other 21 would have their national parliaments implement a new framework setting the national minimum wage to 60 percent of the country’s gross median wage or 50 percent of the gross average wage. While the rules are nonbinding, some fear the effort is counterproductive and could lead to further centralization in Europe.

Decent standards

The notion of an equitable wage has been around since the 1989 charter on workers’ rights and it is supposed to provide a decent standard of living. The question of poor workers is certainly a crucial one. Some people often have several jobs just to scrape by. Besides job instability, their limited purchasing power is a legitimate concern. Hence the strategy is to find an adequate level of income by setting a minimum wage, while tying it to national wage levels (rather than a straightforward European minimum wage).

A high minimum wage – more than 50 percent of the national median wage – can produce unemployment, and in fact reduce the work hours and incomes of lower-skilled populations, especially among the youth, whose unemployment rate is already 13.9 percent in Europe, and as high as 29 percent in Spain and 31 percent in Greece. To make economic sense for the employer, wages should not be higher than the value produced by the employee being hired.

Some economists think that to ensure decent living standards, government should, in the short term, use fiscal policy to compensate for the low wages that businesses pay, thus using redistribution to avoid distortions of the market price system. A longer-term perspective insists that an improved business environment will generate better-paying jobs.

The concept of living standards should consider net income, which includes subtracting taxation and adding welfare benefits. European nations are welfare state societies in which the levels and structure of taxation and benefits vary greatly. Some countries have steeper progressive tax systems, while others have generous entitlements. The variations in taxes and benefits among EU member states make the 60 percent of the median wage standard appear arbitrary.

Inflation matters

Although the proposition has been in the pipeline for at least three years, the current inflation in Europe provides new justification for higher minimum wages. From food staples to energy, prices have risen dramatically in the past year (an annual 8.6 percent increase in the Harmonized Index of Consumer Prices in the eurozone in June). Because of higher prices, it is getting even more difficult for poorer workers to make ends meet; hence the need to protect their purchasing power via new wage regulations.

However, because higher wages mean higher costs, companies will pass on these increases to the consumer, feeding inflation, and thus possibly eroding the purchasing power of workers. That is the same dilemma with broader wage inflation indexing. Another solution could be to permanently reduce value-added tax (VAT) rates or other indirect taxes to make goods cheaper. Such an approach might also provide a good opportunity to reform government bureaucracies and entitlements to make public spending more effective and thus reduce taxes.

Facts & figures

Social dumping

Another justification for this EU-wide minimum wage regulation is the “social dumping” of lower-wage workers from Eastern European countries who find employment elsewhere in the European single market. The argument was made by then-French Secretary of State for European Affairs Clement Beaune (among others) in June 2022. Two issues seem to be worrying policymakers.

First, lower wages give Bulgarians, Romanians and others a so-called unfair competitive advantage compared to other Europeans like the French and the Dutch, thereby supposedly contributing to the offshoring of industrial activity toward the east and to deindustrialization in the west. The idea is to at least increase Eastern European wages by setting rules comparable to richer countries.

Inequality is typically higher in emerging economies because of their development as market economies only about a generation ago.

This resembles the basic protectionist argument found in the anti-globalization narrative. Low wages in emerging economies with less infrastructure and less research and development (R&D) give them their comparative advantage. Inequality is typically higher in emerging economies that developed as market economies only about a generation ago. They are still on the steeply rising side of the Kuznets’ bell curve that ties inequality and development, notably because not all regions have jumped on the bandwagon of development.

Some experts worry that in such a context, forcing a reduction in wage inequality through higher national minimum wages could kill these countries’ main comparative advantage. As for deindustrialization in some Western countries, there is a host of factors, from heavy taxation, legal uncertainty and bureaucratic stifling, to misguided education policies that harm competitiveness.

The second idea is that workers such as plumbers, mechanics and others are willing to work in richer European countries for wages that are higher than those at home, but still lower than what is typical in places like Germany or France. These workers are seen as representing another source of unfair competition within the national labor market of rich countries. Increasing the minimum wage in their home countries is thought to reduce these Eastern European workers’ incentive to work abroad. The poster child of such resentment was the famous “Polish plumber’’ in the middle of the first decade of this century.

Some observers note that despite the social justice guises, the argument is again very much protectionist and hurts the competitive advantage of these workers. And it contravenes the logic of the single market. The argument is even somewhat bizarre for Western countries where such trades are actually lacking workers, either because of educational policies that push young people to get devaluated university diplomas instead of productively promoting vocational training (as in France) or because of demographic reasons. (Accordingly, some might add that rich Switzerland, for instance, should try to encourage higher regulated wages in France since “poorer” French workers are unfairly competing with the Swiss in the French-speaking cantons.)

Average arguments

One problem of indexing the minimum wage to the national median wage, especially at 60 percent, is that if the economy needs more highly specialized jobs with higher wages in successful bigger companies, the median wage will increase, forcing a rise in the national minimum wage. Smaller businesses with a good chunk of minimum wage workers will bear most costs, damaging their profitability, and thus their incentive to hire and invest.

The Austrian Economics Center’s 2017 report on minimum wage argued for taking a territorial perspective. One country is not a monolithic economic territory with a homogenous level of development. If some regions enjoy economic growth, pushing up the national median wage, it means businesses in poorer regions that do not enjoy as much economic growth will end up having to pay higher minimum wages even though their profits have not increased, potentially increasing unemployment. Critics could reply that this would automatically decrease the national median wage, but it is not the case, as jobless people, who do not earn wages, do not affect the median wage.

This process can result in polarization: businesses in poorer regions of emerging eastern economies will find it harder and harder to remain profitable. This would generate more joblessness and thus poverty, as well as territorial imbalances. While the regulation would undoubtedly be short-circuited by undeclared work, some jobless and poor workers will migrate to richer, more dynamic economic territories, provided they can find decent housing they can afford. The problem in parts of Europe is that increased regulation of land use makes finding and paying for housing very complicated and costly. One serious way to increase workers’ purchasing power would be to relax such regulations to reduce the cost of housing.

Frenchized Europe?

Many analysts see the 60 percent of national median wage reference as quite high. Some experts from eastern countries set it rather at 40 percent. Maybe it is no coincidence that the agreement (like several others, such as the Digital Market Act, the Digital Services Act or the Due Diligence Directive) was finalized during the French presidency of the Union. The French minimum wage indeed stands at 61 percent of the median wage, making it the second highest in Europe.

The French have tried to push the adoption of their centralized social model to the rest of Europe.

The French experience with such a high minimum wage is not exactly successful. French unemployment has never dipped under 7 percent for the past 30 years, and most of the time it hovers around 9 percent. Wages tend to gravitate just above the elevated minimum wage. A key reason is that wages up to 1.6 times the minimum wage are partly exempted from social taxes, incentivizing companies to remain under the threshold. However, this in turn impacts the productivity of workers with the weakest perspectives of earning more.

The French have tried to push their centralized social model on the rest of Europe. The problem is not only that it is not efficient, but it is criticized as being undemocratic.

One outcome of the model is that only 7 percent of the French workforce is unionized, mostly in the public sector. Unions are effectively subsidized by taxpayers’ money and enjoy asymmetric power as they regularly block the country’s economy. Public servants enjoy lifelong jobs, union rights and the right to strike.

Scenarios

It is no wonder that countries like Sweden and Denmark rejected the idea of indexing a national minimum wage to the median wage, as they want to keep their traditional bottom-up system of collective wage bargaining between employee and employer. Clearly, the Danish or Swedish models, based on subsidiarity and accountability, are incompatible with the French centralized social model, which seems to be gaining ground in Europe despite its flaws.

From this perspective, some conservative observers worry that this minimum wage initiative is just the beginning. The European project is more and more ambiguous, with rising pressure to increase centralization. Varying taxation systems and welfare rights would eventually pose problems for uniform minimum wage rules. This would be a justification for further intervention to harmonize such systems as well, and a big step closer toward centralization in Europe.