The EU won’t let a good crisis go to waste

The Covid-19 crisis gives EU leaders an opportunity to regain popularity by handing out billions of euros in aid. Such huge sums threaten to weaken the market and could create serious long-term cracks in the European project.

In a nutshell

- EU leaders see the crisis as an opportunity to dole out largesse

- The rescue package increases bureaucracy and inefficiency

- This could deal long-term blows to the European project

Winston Churchill is alleged to have once quipped that one should “never let a good crisis go to waste.” When the European Commission proceeded to cobble together its historic 750 billion-euro Covid-19 rescue fund, it offered a perfect illustration of how that political wisdom could be transformed into reality.

At the outset of the year, dark clouds hung over Brussels. Ranging from European Union leaders’ flagging popularity, to the impact of Brexit on the new long-term budget, to the wobbly Italian economy, there were serious grounds for concern about the continued viability of the euro, and perhaps even of the European project.

Then the Covid-19 pandemic arrived – a perfect storm that caused enormous damage but also brought great opportunity. After having seemed destined to leave office in disgrace over her handling of the immigrant crisis, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made a spectacular political comeback, buoyed by the country’s impressive handling of the crisis. French President Emmanuel Macron was less fortunate, taking significant flak for his sluggish response to the virus. Yet, he still improved his standing, as did many other European leaders.

EU limbo

The pandemic breathed new life into the sputtering Franco-German tandem. Forgotten are the days when Chancellor Merkel complained of having to constantly clean up after President Macron’s blunders on the international scene in relations between France and the EU.

With Berlin and Paris in sudden agreement that 750 billion euros in borrowed money would work wonders, it was left to the “frugal four” – Austria, Denmark, Sweden and the Netherlands – to organize a rearguard action, seeking to reduce the share of handouts versus loans in the total package. Meanwhile, the previously controversial long-term budget was passed with minimal adjustment. Gaping holes left by Brexit will be covered. The frugal countries were bought off with rebates on their net contributions.

The question is whether this will be a breakthrough for the European project or the final nail in its coffin.

Will this be remembered as a great breakthrough for the European project, or the final and costliest nail in its coffin? The wisdom of doling out such vast sums with so little accountability is questionable. The track record of abuse of funds received from Brussels should perhaps have given leaders pause. But the urgency of the political crisis effectively overshadowed any such consideration.

Judging from the jubilant reactions of the main players once the deed was done, it is also obvious that something bigger was at stake than simply helping those worst hit by the pandemic. In the words of President Macron, “This is the most important moment in the life of our Europe since the creation of the euro.” However, if the real purpose of the rescue fund was to save the euro, then there is plenty of reason to question the wisdom of the initiative.

To those who view the euro crisis as caused by the halfway house of a currency union without a fiscal union, the rescue fund provides the first step toward a solution. With the EU on track to becoming a transfer union, we may now be looking at the eventual creation of a United States of Europe. But the prospects for this vision to be realized remain dubious, at best. In the meantime, the most likely outcome is that the EU will be stuck in a limbo, with lingering resentments and deep disagreements over the specifics of what has been agreed.

Moral hazard

The most immediate impact of the rescue fund will be to paper over such problems. The injection of borrowed funds will provide a short-term economic boost, and the handouts to countries in the south will alleviate grievances that those in the north had been shamefully slow to act upon.

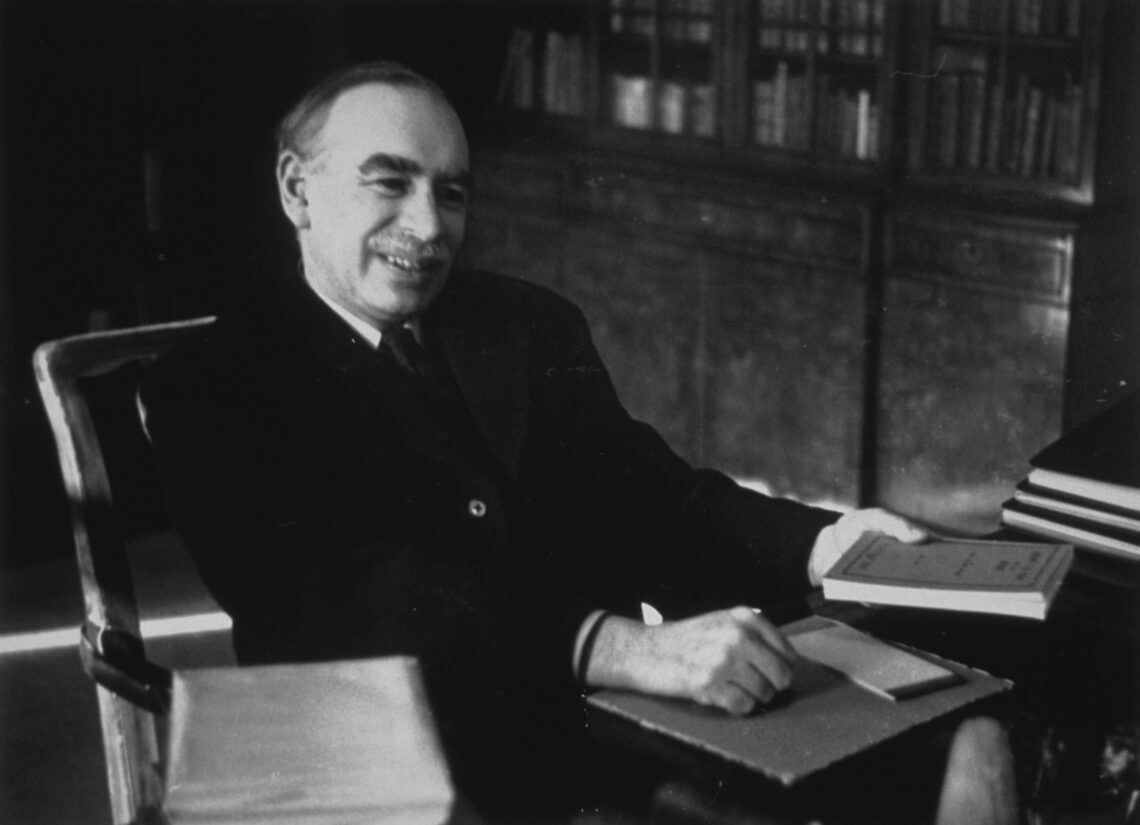

Readers may recall John Maynard Keynes’s classic metaphor of paying people to dig holes in the morning and to return to fill them in the afternoon. The main purpose is to boost demand. How the money is spent is less important. This is where the Covid-19 rescue fund begins to look more problematic. Since the crisis will be a long haul rather than a short, sharp shock, how the money is spent will become increasingly important. There are three major problems.

The first is that any regime based on a political imperative to get money out the door fast will be plagued by moral hazard. Working under severe stress, with complex new procedures, government agencies will be at a serious disadvantage against unscrupulous operators eager to help themselves to a piece of the action. This goes over and above the obvious risk that organized crime groups will deploy their skills in setting up bogus operations to claim a large chunk of the support.

Even in countries with well-ordered judiciaries and high standards of respect for the rule of law, the temptation for enterprises to fudge their books will be strong, while authorities will be overloaded by the need to enforce the rules. In the end, much of the money will be disbursed to beneficiaries who do not qualify and will not produce the expected positive response.

‘Deadweight loss’

The second problem is that the rescue fund will be associated with two forms of direct “deadweight loss” (a cost to society created by inefficiency). The machinery needed to manage the fund will consume resources that could be devoted to productive undertakings. While it may be argued that the gains made from preventing a wave of bankruptcies will outweigh such short-term transaction costs, there is also a considerably more detrimental longer-term cost.

By making public funds available for bailouts, Brussels will enhance the role of what economist Jagdish Bhagwati once branded as “directly unproductive profit-seeking activities.” The point is that entrepreneurs are offered ways to profit by undertaking activities that do not produce goods or services. If such activities are more lucrative than traditional productive entrepreneurship, the outcome will be a deadweight loss in current output.

Placing a premium on relations with bureaucrats rather than customers will have a negative impact on market efficiency.

Placing a premium on learning skills that pay off in relations with bureaucrats, rather than those with suppliers and customers, will also have a seriously negative impact on longer-term market efficiency. While this problem is not new, giving the transfer bureaucracy such a huge boost will make the challenge much thornier. The result will be to further erode the traditional entrepreneurial culture of seeking gain by staying ahead of the competition in the marketplace.

Bureaucracy rules

The third problem is that the rescue fund puts bureaucrats, instead of markets, in charge of allocating funds. There are good arguments both for boosting demand by injecting money straight into household budgets (a practice dubbed “helicopter money”) and for providing targeted relief to the poor. But the case for taxpayer bailouts of failing businesses is much less obvious. While most enterprises remain sound and can thrive once demand comes back, there are also many that were on the ropes before the pandemic.

A gigantic intervention to protect jobs in the short term means many companies that should have been allowed to fail will be rescued. This will have profoundly negative implications for restructuring and revitalizing the European economy. Above all, it begs the question of whether bureaucrats are better than bankers at lending to firms in need.

The fundamental geopolitical test will be whether post-Covid Europe can stand up against the perceived threat of China muscling in on European markets. Some have argued that the EU needs to mobilize its strong regulatory capacity. This is a shallow argument. While it is true that competition policy has a good track record, the results achieved against Gazprom have not been impressive.

Entrepreneurial dynamism

The real potential of the European project lies in the dynamism of its entrepreneurial sector. China has already bypassed Europe in many areas of scientific achievement. What remains is the critical step from invention to innovation. This is where institutions favoring flexible private entrepreneurship become critical. Russia’s example shows that if institutions do not favor entrepreneurship that can commercialize technological breakthroughs, then even the brightest minds will only get you so far.

The colossal rescue operation will increase centralization and nonmarket intervention.

The future of the European economy hinges on whether that link can be protected, and preferably, enhanced. China learns fast. The current trend in Europe, meanwhile, is toward unlearning by not doing. The colossal Covid-19 rescue operation will enhance that process, increasing centralization and nonmarket intervention.

Allowing the pandemic to trigger a wave of bankruptcies would have brought mayhem. But it would also have made room for Schumpeterian creative destruction. Given that economic demand will be much different post-Covid than it was before, allowing markets to lead the way toward restructuring productive capacity would have been advantageous. The European airline industry is not alone in being long overdue for restructuring.

Southern discomfort

Those who rejoice that the euro has been saved (for now) may also consider that the essence of the arrangement has been to provide German manufacturers with a competitive edge against producers in the south, who face less favorable institutions and are precluded from compensating via devaluation. If the euro were to collapse, the value of the deutschmark would soar.

Repeated interventions in the south are the price German taxpayers are paying for retaining the edge of an undervalued currency. With every new bailout comes not only more erosion of budgetary discipline and a greater emphasis on working with bureaucrats, but also an increased political sense of entitlement to be bailed out. With the Covid-19 rescue fund, the latter has gone into overdrive.

As the bills for the rescue begin to come due, and the economic recovery is sluggish at best, the early triumph of the fund may well translate into a Pyrrhic victory. While governments in the frugal countries will face growing criticism for having sold out, prompting a return of demands to exit the EU, governments in the south will face growing resentment over imposed restrictions on how money can be spent. Countries like Hungary and Poland will fight to keep rule-of-law clauses at bay.

With Ms. Merkel out of the game, President Macron will face the specter of a renewed showdown with Marine Le Pen. As the social costs of the pandemic begin to bite, his image of being a technocratic “president of the rich” will not be helpful. In Italy, anti-EU Matteo Salvini may return to power. The bribe implied by the rescue package may still turn out to have been too small to neutralize such challenges. Meanwhile, the Chinese are getting ready to up the ante.