The U.S. mulls more Covid-19 bailouts for states

As the U.S. government wrangles over another round of Covid-19 relief, one of the thorniest issues is whether to lend more federal money to states and local governments. Instead of covering the shortfalls in tax revenue, more federal aid merely increases debt.

In a nutshell

- The U.S. has already doled out $325 billion in Covid-19 relief to states

- More federal money to local governments expands the already hefty national debt

- States have the tools to make the necessary fiscal adjustments

In debating another round of Covid-19 relief, the United States Congress is deadlocked over additional federal money to state and local governments. While it is true that business closures and job losses have reduced tax revenue, claims of pervasive fiscal disaster are overblown. Further bailouts would exacerbate the U.S.’s enormous federal debt and reinforce the profligacy that plagues state finances far more than the pandemic.

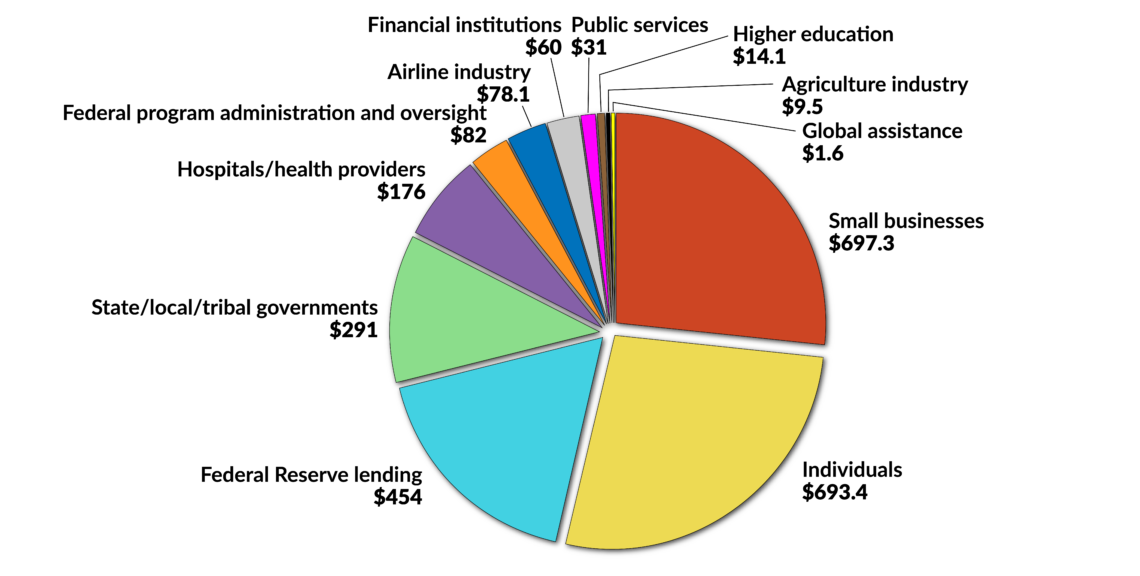

To date, the federal government has authorized about $325 billion in coronavirus aid to state and local governments as “revenue replacement” and to supplement healthcare, education, housing, transit and other safety net programs. For its part, the Federal Reserve has established a $500 billion loan fund for states and large municipalities.

In May, the Democratic majority in the House of Representatives approved an additional $875 billion for states and localities as part of a $3 trillion stimulus package that the Republican-led Senate refused to consider. In turn, Senate Democrats blocked a Republican relief bill – dubbed the “skinny” alternative, at $500 billion, without yet more aid for states and localities. The latest offer from the White House, totaling $1.5 trillion in new spending, includes about $300 billion for states and local governments. It has drawn bipartisan criticism, with Republicans opposed to the price tag and Democrats demanding more.

Managing the lockdown

Democrat governors are warning of fiscal calamity, a useful cudgel against President Donald Trump in an election year. Politicians tend to regard spending as the remedy for every crisis – contrary to all evidence of inefficacy. As noted by scholar Amity Shlaes, “[A] government that wants to grow, wants to foster fear because then people suspend disbelief and give in to whatever the government wants.”

The onset of the Covid-19 outbreak reduced state and local tax revenue by $13 billion (3 percent) between the first and second quarters of this year. Sales and excise tax receipts recorded the largest decline, at 6.4 percent, while personal and corporate income taxes fell by a combined 1.7 percent. In contrast, property tax collections increased slightly, by about 0.7 percent.

Politicians tend to regard spending as the remedy for every crisis – contrary to all evidence of inefficacy.

Most states and localities are managing the economic lockdown rather well, given the circumstances. The full brunt of the crisis has yet to be felt because many states extended deadlines for tax payments that otherwise would have been due in April 2020. But the seven-point drop in U.S. unemployment since April bodes well for a relatively quick rebound, as does the health of the housing market.

The Wall Street Journal reported that August sales of previously owned homes rose 10.5 percent (on an annualized basis) – well ahead of last year’s levels. Analysts say many buyers are looking to add space for home offices. That is welcome news to local governments, for which property tax collections constitute some 72 percent of the tax base.

State and local finances would have been much worse were it not for the sustained gross domestic product (GDP) growth and booming stock market of recent years, which considerably strengthened budget reserves. For example, states’ total balances have more than tripled (on a dollar basis) since the depth of the Great Recession – from $31.6 billion in 2009 to $118.8 billion in 2019 – according to the National Association of State Budget Officers (NASBO).

Spending cuts

Going forward, the decline in tax revenue is manageable if states can restrain spending. The federal aid has more than made up for the tax receipts lost to the lockdown. Congress and the White House have authorized a whopping $325 billion in Covid-19 relief for state, local, and tribal governments (out of $2.6 trillion in total pandemic relief funding).

Spending cuts need not decimate core functions of state and local government given the spending increases of the past three years: 3.4 percent in fiscal year 2018 compared to fiscal year 2017, and 5.7 percent in fiscal year 2019 over fiscal year 2018 – for a total of $2.1 trillion in fiscal year 2019.

Facts & figures

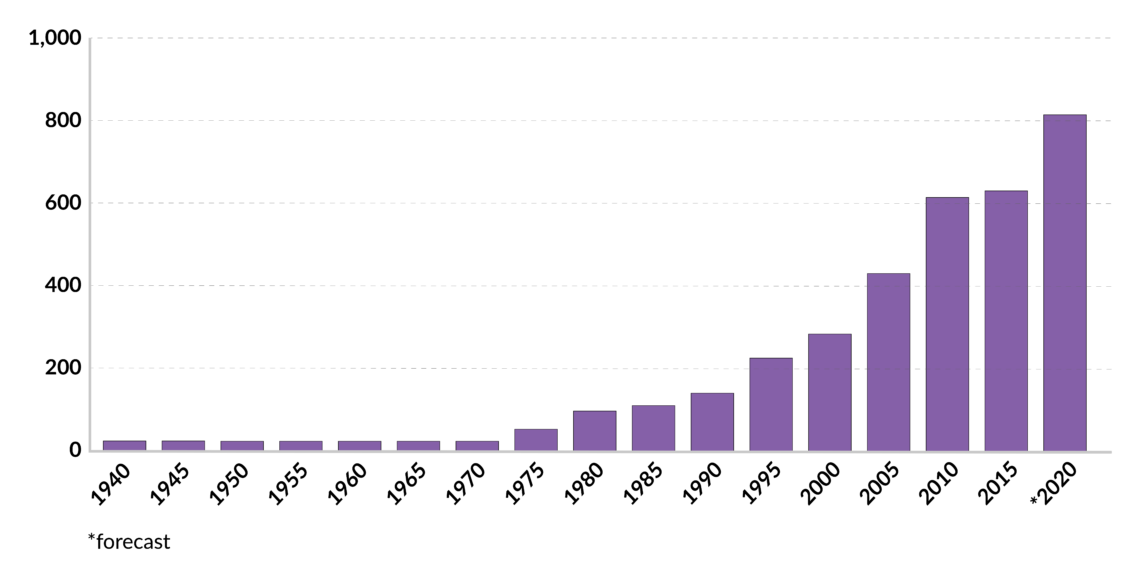

The Covid-19 relief also supplements the ever-generous federal outlays paid annually to states and localities. This year alone, the so-called federal grants in aid will exceed $791 billion – or about a quarter of states’ revenues overall. The annual aid is authorized by Congress for healthcare, education, transportation, environmental protection, labor initiatives, community development and homeland security, among other uses.

The number of programs through which ordinary federal aid is appropriated – nearly 1,400, at present – has tripled since the 1980s, according to Chris Edwards, director of tax policy studies at the Cato Institute. Some of the funds are necessary to cover services mandated by Congress. But more generally, the federal largesse enables states to expand discretionary spending.

Most states were able to bolster their “rainy day funds” as a result of economic growth that more than made up for the losses of the 2010 recession. The aggregate balance in reserve funds reached an all-time high of $118.8 billion last year (13.7 percent of general fund spending). Since fiscal year 2010, in fact, the median rainy day fund balance, as a percentage of general fund spending, has increased from 1.6 percent to 7.8 percent, according to NASBO.

Challenges

Several states do face serious fiscal challenges because of Covid-19. For example, with oil prices in a slump due to telework and reduced travel, energy-centered states such as Texas, Oklahoma, Alaska and New Mexico have been hit hard. But a handful of other states are facing gaping deficits and massive debt as a result of long-standing budget imprudence, not Covid-19.

States’ unfunded public pension systems also pose a significant problem even in the best of times.

Illinois officials, for example, have consistently failed to shore up the state’s reserves, which total a measly 0.3 percent of general fund expenditures this year – or enough cash to last about 15 minutes of state spending, according to the Volcker Alliance, a government watchdog group. Pennsylvania posts a pitiful 0.9 percent, while Nevada and Kansas each have effectively zero.

States’ unfunded public pension systems also pose a significant problem even in the best of times. Unfunded retirement liabilities, totaling $855 billion in the aggregate, constitute the largest proportion of the $1.4 trillion in state-level debt, according to the think tank Truth in Accounting, which publishes the annual Financial State of the States report. On a per capita basis, New Jersey is the most indebted state, with a shortfall of $57,900 per taxpayer. Illinois ranks second, at $52,000, followed by Connecticut, at $50,700.

Opponents of additional bailouts also stress that the U.S. simply cannot afford to increase its federal debt, which is expected to surpass 100 percent of GDP next year, according to the Congressional Budget Office.

States possess an abundance of fiscal power to adjust to the temporary loss of tax revenue resulting from the Covid-19 crisis. First and foremost, they can reduce the inessential spending that fattens most state budgets. (The top two program areas of increased state spending in recent years have been “Transportation” and “Other.”) But overreliance on federal bailouts – particularly considering decades of increased grants in aid – undermines the balance of power between the states and the federal government and subordinates the will of each state’s voters to the collective interest of other states.