Broken rules and opportunistic socialism

With the Covid-19 crisis bearing down on economies, all efforts at maintaining fiscal responsibility in the eurozone have been abandoned. Pandemic policies in the eurozone may add new fiscal rules – ones which could backfire entirely.

In a nutshell

- Fiscal responsibility in eurozone countries seems non-existent

- The EU might implement new fiscal rules that centralize power

- Pandemic policies in the eurozone could lead to a bigger crisis

The creation of the euro came with strings attached, especially regarding public finance. For countries adopting the currency, national budget deficits of up to 3 percent of gross domestic product (GDP) were allowed. Public debt could not exceed 60 percent of GDP. Countries that entered the euro with higher debt had to fall in line within a few years.

Those rules ensured that public expenditure would be financed by current taxation, so that policymakers and their constituencies would not enjoy a free ride at the expense of future taxpayers or investors. Moreover, they shielded the European Central Bank from pressures to create inflation and reduce the real value of the debt.

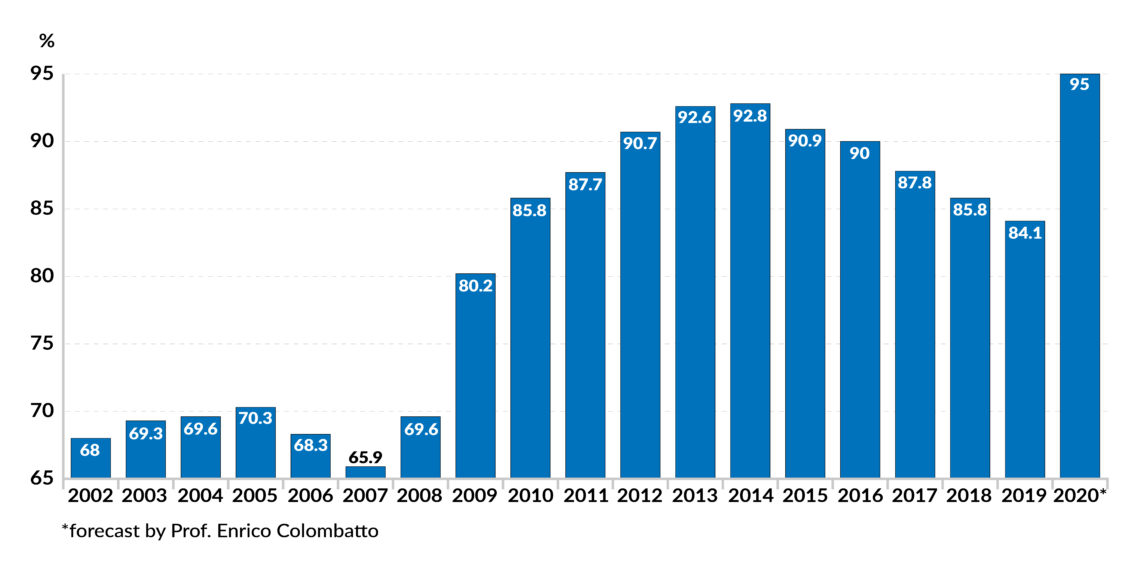

Those rules have been widely disregarded. Over the past decade, most eurozone countries’ budgets have been in the red. This year, the average deficit will probably rise to around 9 percent. Public indebtedness in the eurozone has taken a similar trajectory: it was 68 percent in 2002, reached 91 percent in 2015, and will probably be around 100 percent in 2020. Predictions for 2021 are unreliable, but nobody expects budget deficits to drop to 3 percent or lower. Public indebtedness will grow.

EU authorities have de facto given up the original stand and have not yet clarified what fiscal discipline will mean in the future. There are several options available.

Facts & figures

Euro area debt-to-GDP ratio (%)

Enforcing the rules

In one scenario, Brussels and Frankfurt soon revert to the initial monetary vision and enforce the original fiscal rules. This is the least likely perspective. The member countries found it difficult to comply with the rules even when their economies were relatively healthy. Today, they would never accept such rules when growth is slow and the demand for pandemic-related relief is set to remain high for months.

Returning to fiscal discipline would not only require a quick end to the pandemic. It would also require significant drops in regulation and taxation and a populace that is no longer afraid of new potential shocks. Economies must become more flexible and individuals less dependent on government action.

Economies must become more flexible and individuals less dependent on government.

Introducing fiscal rigor and separating the central bank from political pressure are measures that call for a radically different cultural approach to the notion of “economic union.” They also necessitate new leaders that share such a vision and enjoy adequate support. None of this will materialize any time soon, since the prevailing cultural context is opportunistic socialism.

Changing the rules

A more realistic scenario would include different rules. Rules are inevitable because they legitimate political authorities and large bureaucracies. Brussels and Frankfurt will not admit that rulemaking is ineffective and that it can easily turn into a source of tension. Far from deregulating, EU authorities will probably strive to present a new package of “better” rules, which will preserve and expand their power but will not provoke much opposition among the member countries.

As we underscored in a previous report, the European authorities have clarified that they intend to keep interest rates low and turn cartwheels to inject at least some inflation into the eurozone. Paris and Berlin gave the green light to this course of action long ago. From a public-finance viewpoint, the ECB wants to ensure that national public debts are sustainable and comply with its duty to guarantee financial stability. Thus, the European Central Bank will “do what it takes” to lower the debt-servicing cost and reduce the debt’s real value through inflation.

In other words, the ECB’s agenda includes a two-pronged solution to the public finance problem. On one hand, it tries to cut the debt-to-GDP ratio by restraining the rise of nominal debt and expanding the nominal GDP. On the other hand, it claims that there is no public finance problem. It argues that a 100 percent debt-to-GDP ratio is nothing unusual, let alone astonishing, and that a zero real interest rate on treasuries is not outrageous – in fact, it is better than what one can receive on cash.

One can speculate on what kind of rules suit such strategies, to what consequences these might lead, and what could go wrong.

A ‘convenient’ solution

History shows that strict discipline is problematic in two respects. Weak countries – those addicted to profligate spending – perceive such rules as a loss of sovereignty. Worse still, local politicians would be more than happy to add fuel to the fire and find a convenient scapegoat for their own inefficiencies. Moreover, strict rules are not credible since even the economically “strong” countries break them and set a precedent that others exploit.

Loose fiscal responsibility and partially centralized policymaking are an attractive solution for most players in the eurozone. The European Union is already heading in this direction, albeit at the slow and hesitant pace that has characterized the bloc over the past three decades.

Loose fiscal responsibility and partially centralized policymaking are an attractive solution for most players in the eurozone.

Centralized policymaking would solve indebtedness: the EU would replace the treasuries of its member governments. Loose rules would apply to the new debt that the Union issues and dictate the sharing of the debt-financed revenues among the member countries. Fragile countries would see their public-finance problem solved overnight by debt centralization and rejoice at the idea of transforming an economic issue into a matter of political debate.

Financially sound countries will complain to save face and eventually give in. They would see this strategy as a convenient way of defusing a time bomb (the collapse of the Union), removing the decision-making mechanism from the limelight and drawing a line between central and local fiscal responsibilities. European politicians and bureaucrats would see their power expand significantly.

Taxation, inflation

What about the consequences? Having loose rules for a more or less centralized European treasury means that the EU will soon need more tax revenue to sustain its credibility on financial markets. Taxpayers will be hit once again. Interest rates will also stay flat to ensure that the cost of servicing the European debt remains low (and the new pressure on the European taxpayers remains moderate) and that investors continue to buy treasuries, for lack of alternatives.

However, if interest rates fail to do the trick and financial tensions emerge, debt monetization would follow, and the central bank would buy the treasury bonds nobody wants. If that happens, inflation will be unavoidable, hitting savers, retired people and many on fixed incomes.

The consequences of Europe’s policy could bring the system crashing down.

Although such a system of centralization and loose rules might work in the short term, it is far from certain that it will ever come to fruition. European authorities would need to speed up the centralization process now, before people stop panicking and start having second thoughts about grand solutions. EU leadership has not shown the will or the ability to move fast.

Moreover, the consequences of Europe’s monetary policy could bring that system crashing down. Europe is characterized by a liquidity glut: individuals and commercial banks are looking for investment opportunities and are increasingly tempted by unreliable debtors and projects promising positive returns. These investments could easily turn into a time bomb that explodes when loans are not paid back, households lose money and commercial banks face a new crisis.

If that were to happen, the EU would come under severe pressure and possibly even collapse. In some countries, enormous nationalization programs would follow, trade barriers would flourish, and new injections of monetary instruments would finance public expenditure.