Europe’s border agency searches for support

Created in 2004 to protect the Schengen system’s external borders, Frontex has often met criticism for both inefficiency and overzealousness. But with evolving migration crises from Belarus to Afghanistan, the EU risks a state of chaos.

In a nutshell

- Frontex faces yet another migration challenge

- The agency is not up to the task

- Fragmented responses risk a new crisis

Frontex, the European Border and Coast Guard Agency, was created in 2004 to help the European Union member states protect the Schengen system’s external boundaries. Funded from the EU budget and with contributions from the Schengen countries, it has seen numerous problems in recent years and had its fair share of critics. Now facing another possible crisis, with migration flows increasing along several fronts, policymakers are left asking whether and how the agency can adapt.

After initial reforms at Frontex in 2011, the crisis triggered by a wave of migration in 2015 forced the European Commission to draw up a plan to strengthen the security of the EU’s external borders. Frontex proved unable to manage the migratory flow due to scarce support among the member states and, above all, to the insufficiency of its means and staff. It was also demonstrated that the agency did not have the authority to conduct border control operations or rescue migrants at sea.

For these reasons, in December 2015, the Commission proposed a new agency to replace and extend Frontex’s mandate in managing the EU’s external borders. Thus, in 2016, the agency was strengthened. Its mandate was extended from migration control to border management, with more responsibilities in fighting cross-border crime and search and rescue in maritime border surveillance, using ships, aircraft and drones. The Frontex Situation Center for monitoring the external borders – 24 hours a day, seven days a week – was launched.

Mission control

To ensure the agency’s operations, its budget was gradually increased, from the 143 million euros initially foreseen for 2015 to 238 million in 2016, 281 million in 2017 and 322 million euros by 2020. The 2021-2027 Frontex budget provides for a total of 5.6 billion euros. The agency’s staff also grew from 402 members in 2016 to around 1,500 in 2021. However, this development of its capabilities was not followed by a parallel growth in administrative capacity.

In the Mediterranean, Frontex has three missions, dubbed Themis, Poseidon and Minerva/Indalo.

The first is based in the central Mediterranean and arose in 2018 to replace Triton, launched four years earlier. With Themis, Frontex focuses on surveillance against illegal entry into the EU’s maritime borders and related transnational unlawful activities, including fundamentalist terrorism. The patrol areas are to the east, considering the flows from the Balkans in which drug smuggling has developed. Poseidon and Minerva, on the other hand, concern the Eastern and Western Mediterranean.

Frontex vehicles and agents in these three cases assist local coastal authorities in monitoring the sea areas affected by migration. Another mission is also active in the Western Balkans to assist member states in managing external pressure.

Assessing the numbers

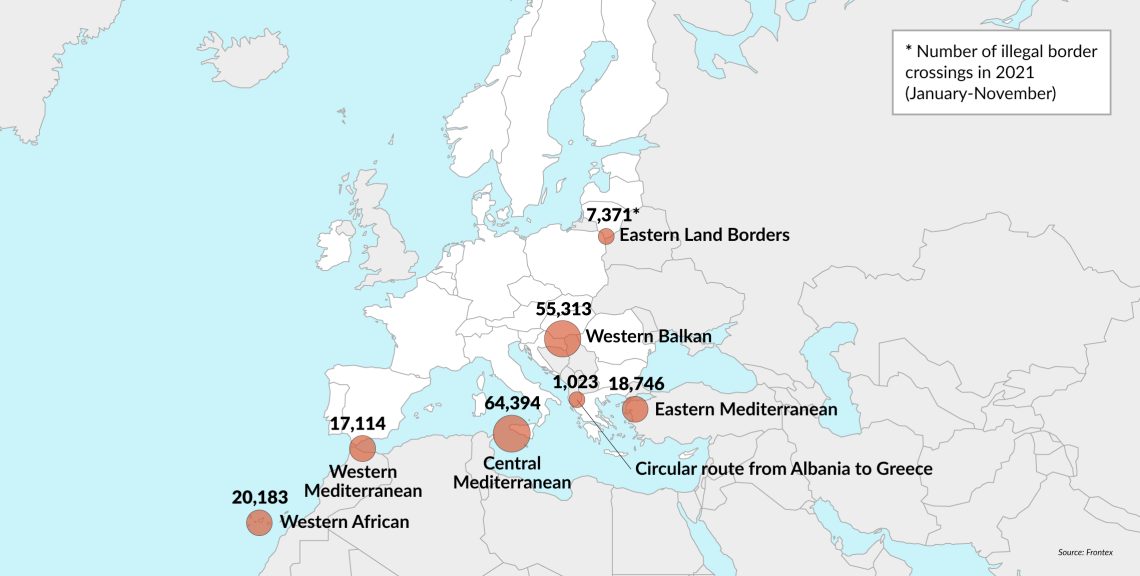

The pandemic has not stopped the arrival of illegal immigrants, judging by the latest Frontex data. In the first ten months of 2021, there was a striking increase in arrivals to EU countries, up 70 percent compared to the same period in 2020. Compared with the pre-Covid period (2019) data, the growth is still evident, at 45 percent. Last October, 22,800 illegal immigrants arrived in Europe – a 30 percent increase compared to October 2020 and 18 percent more than in the same month of 2019.

The most significant increase is found in the Central Mediterranean, and therefore in Italy and Malta, with 55,000 arrivals, up 91 percent compared to 2020. In October alone, which saw 6,240 arrivals, the rise was 85 percent compared to 2020 and 186 percent compared to 2019. The agency has emphasized, in particular, the “significant development in October” regarding arrivals by the sea of illegal immigrants from Turkey to Italy. These are mainly Tunisians, Sinhalese and Egyptians, with the latter mostly arriving from the Libyan coast.

Some in the European Parliament have considered the agency’s actions inefficient, while others feel it has acted too harshly.

The Frontex report also notes a heavy increase in arrivals via the Balkan route from the eastern border, which has been the focus of public attention due to a tug-of-war between Poland and Belarus in recent months. From the east, 8,000 people have arrived in Europe since the beginning of 2021, representing a 1,444 percent increase, bringing us back to the numbers of 2015. The arrivals from Africa to Spain have not fallen off either, with a 14 percent rise from the Western Mediterranean route. And especially toward the Canary Islands – Spanish overseas territory and therefore the EU – significant increases are evident: 46 percent compared to 2020, and even 1,020 percent compared to 2019.

However, these numbers are still not overwhelming. If in Italy today there are about 128,000 refugees (0.2 percent of the population), in France there are 408,000 (0.6 percent), in Germany 1,147,000 (1.4 percent) and in the “small” Sweden 254,000 (2.5 percent). Irregular arrivals to Italy by sea have grown compared to the lows of 2019, but they are around 45,000 per year, compared to 150,000-180,000 per year in the 2014-2017 period.

Facts & figures

In terms of international agreements, after several months of tensions with Turkey, EU member states announced their willingness to renew the migration agreement that expired in March 2021. The EU Commission lined up an additional 585 million euros for a “humanitarian bridge funding” for the whole of 2021. The high-level meetings between European and Turkish institutions are a testament to their strong interest in brokering a deal, though they also reflect underlying disputes yet to be settled.

Reality check

Over the years, Frontex has often found itself under criticism. Some in the European Parliament have considered its actions inefficient, while others feel it has acted too harshly. The first group of detractors includes those who have focused on the continuous increase in migratory flows and repeated emergencies on the most active fronts. The second group of critics includes the Greens and Socialists and Democrats who, backed by NGOs and various associations, have accused Frontex of having helped the Greek authorities illegally reject hundreds of migrants during the refugee crisis that exploded in January 2020. On that occasion, some deputies considered demanding the resignation of the agency’s controversial director, Fabrice Leggeri of France.

Despite these criticisms, Frontex can be strengthened in the coming years. Leggeri, in a hearing before the Schengen commission of the Italian parliament, admitted the possibility of new agents and a further increase in weapons and means. The opening of a new migration front in Belarus in 2021 and the specter of a resumption of immigration from Afghanistan are pushing the EU to apply stricter border control measures. These include an emphasis on a stronger Frontex.

A fundamental question of whether to link the Frontex to the Schengen borders or start further beyond, in the Sahel and the Middle East, remains unanswered.

Recent talk has focused on migrants – around 4,000 – arriving from Afghanistan and other troubled countries, such as Iraq and Syria, who ended up on the border between Poland and Belarus. Will there be a Balkan migration wave this year due to the collapse of Afghanistan? If we look at the more recent past, it appears unlikely.

Based on data of those who observe European borders every day – Frontex and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) – of the 2.5 million Afghan refugees registered by the UN agency last summer, the majority had moved to neighboring countries, especially Pakistan and Iran. Only about 400,000 of these refugees, or 16 percent, received protection in European countries. Between 2008 and 2020, European countries (including non-EU countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway and Switzerland) received 600,000 asylum requests from Afghans, accepting 310,000. In all, 290,000 people were rejected, and some 70,000 have already been repatriated. Another 92,000 Afghans were awaiting the outcome of their asylum application in recent months.

Scenarios

According to Italian Prime Minister Mario Draghi, the heterogeneous responses of individual European governments to these arrivals risk continuing into 2022 and leaving the European Union in a state of disorder – or even chaos, if the wave of migration begins to grow exponentially.

Trying to respond, the European Commission has invested in deepening cooperation between member states, such as the forthcoming Assisted Voluntary Return and Reintegration Strategy project. However, the promise of member states to promote the adoption of assisted voluntary return still rests on a somewhat fragile basis.

Clearly, Frontex cannot act alone: there needs to be coordinated support from the member states for field operations. The EU’s border control agency has grown robustly in recent years, but the number of migrants coming from fragile or failed nations will increase, while the agency will be able to do little with thousands of people at the doors of Europe. A fundamental question of whether the Frontex strategy should be linked to the Schengen borders or start further beyond, in the Sahel and the Middle East, remains unanswered.

Such a gear change will most probably not occur in the immediate future – leaving the European borders porous towards irregular migratory flows, a state of affairs that will turn into a guillotine over the head of a shortsighted political class.