Generative artificial intelligence: Rise of the machines

The latest technological advances suggest that the “AI revolution” will deliver socioeconomic turmoil, massive wealth redistribution – or both.

In a nutshell

- AI advances will likely replace entire industries of human workers

- Mass unemployment will fuel resistance and social strife

- Governments may respond with universal basic income programs

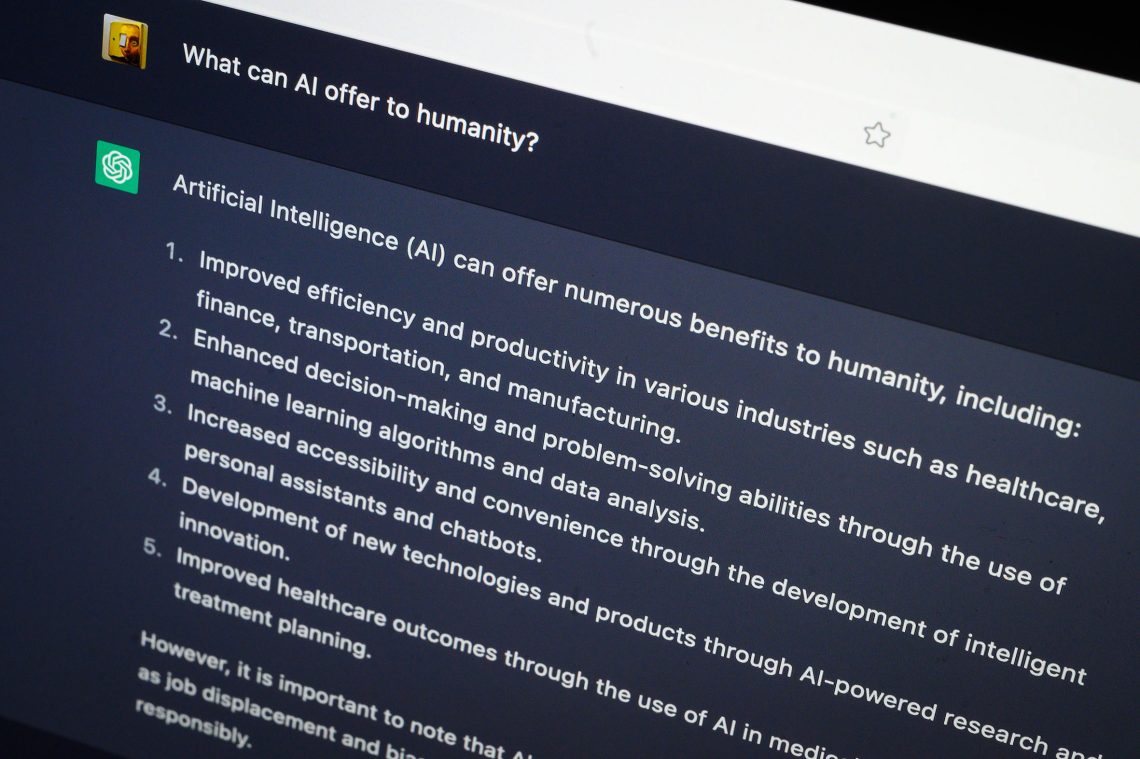

Recent months have seen a lot of conversation about the dangers and opportunities presented by the latest advances in artificial intelligence (AI) technology. Most of this has been stirred up by ChatGPT, a generative AI chatbot created by the Microsoft-backed OpenAI and launched to the public in late 2022. The software’s impressive capabilities – formulating articulate, (usually) accurate responses to complex questions, and creating text often indistinguishable from that of a human writer – have reignited debates about “the robots taking over.”

Much of the public appears divided into two camps: the technophiles, excited about “upgrading” our already symbiotic relationship with computers; and the modern-day Luddites, foes of progress who fear these new machines just as their predecessors feared textile mechanization.

Human obsolesce?

Against those sounding the alarm over AI, one hears several common arguments:

- Limited scope: AI can automate certain tasks, but it is unlikely to completely replace all human labor.

- Job creation: The implementation of AI can also lead to the creation of new jobs in fields such as technology, data analysis and AI development.

- Human skills: Many jobs require human skills, such as creativity, empathy and critical thinking, which AI cannot replicate.

- Uncertainty: The impact of AI on employment will depend on how it is implemented and regulated, and it is impossible to accurately predict its exact effects on the job market.

While it is true that AI can only automate certain tasks, that is only true for the present. Over time, AI applications will continue to master a greater share of skills. Moreover, we have not yet reached so-called artificial general intelligence (AGI), which, unlike today’s “narrow AI,” is expected to have the ability to perform any intellectual task that a human can. When it comes to jobs requiring supposedly uniquely human skills – as well as new technology jobs that the AI industry might create – the math simply does not add up. There are only so many creative professionals and AI developers that an economy can absorb.

Globally, most human labor requires little to no empathy and no tech specialization. In the West, particularly, most “middle-class” jobs can already (or will very soon) be replaced by a purpose-built AI, from accounting to copywriting and education to architecture. Finally, the appeal to “future uncertainty” is a common nonargument, similar to “nobody has a crystal ball” and “only time will tell” – an evasive maneuver often used by those intending to obfuscate the question under scrutiny and to wiggle out of a losing position in a debate.

Of course, none of these talking points are new. What is new is who is making them – or rather, what is making them. Because these four arguments were not made by a person, but by ChatGPT, in response to the question of human obsolesce. This is why this time it is different: AI cannot be compared to the printing press, or to assembly robots putting together cars and fridges. It cannot even be compared to modern software advances, like computer-aided architectural design, facial recognition for policing or robo-advisors for investing.

This time is different

There is a reason why the industrial revolution and later technological advances did not make humans redundant. As our ChatGPT interlocutor aptly noted, in the previous paradigm shifts, material-oriented jobs requiring manual labor or endless repetition (like Ford assembly line workers or literal cookie cutters) were taken over by machines; but this still heralded a transition to more cognitive-oriented jobs and the service industry.

Especially in the West, these are the jobs that keep the entire economic edifice standing. New software and other technology advances certainly helped us perform them better, more accurately and more efficiently, but there was never any widespread fear that Excel would make accountants obsolete. Even the most recent, cutting-edge breakthroughs, from algorithmic trading to robotic surgery, are still mere tools that do not pose existential threats. That is because even the most advanced computer programs are designed by, and contain the knowledge of, one human or one team of humans – and cannot possibly compete with the skills and talents of all the humans in an entire industry.

The AI applications that will follow ChatGPT and its peers, however, will likely enjoy the skills and talents of all the human workers in an entire industry. And they will probably encompass much more: everything that was ever written, recorded or created by human creativity since the dawn of that given industry. This is the kind of knowledge that no human, group of humans, or humanity itself can hope to match.

Gradual revolution

What can we expect from this paradigm shift? It will most likely happen gradually and incrementally, at least until a certain “critical mass” is reached. At first, there will be efforts to adjust and adapt. For instance, we may see a renaissance of manual labor. With the mass adoption of AI, if “software” advances outpace those of “hardware,” one can imagine conventionally lower-status workers like plumbers, gardeners and manicurists earning more than business consultants, copywriters or accountants. Those “uniquely human skills” will indeed come into play – only they will be found not in our capacity for critical thinking but in our opposable thumbs.

This kind of initial stage may linger for some time. With large numbers of people looking for any job at all, the dynamics of supply and demand will make it cheaper to hire a human to perform manual tasks instead of investing in the development of a super-specialized machine. But that is bound to change eventually, after inevitable innovations and those same supply and demand dynamics. The cost of the necessary specialized machines will ultimately come down, wiping out the manual professions too.

If jobs in the production of nonphysical goods (like finance and architecture) are the first to go, and jobs in material production are soon to follow, what will remain is purely personal services, like psychiatry or personal training. Humans may well still prefer to receive such services from members of their own species, at least for as long as it remains affordable to do so. But as the price of AI continues to tend to zero, what is “inconceivable” today will become commonplace tomorrow.

Ultimately, highly specialized workers whose services combine both the physical and personal will be most likely to remain valued. These roles could range from those precious few “AI developers” that will remain necessary or child psychiatrists specializing in autism. But they would be few and far between – the “best” that humanity has to offer – as well as prohibitively expensive for most people.

Naturally, there will be attempts to stop or slow these changes along the way. In the private sector, we can expect legal challenges over intellectual property rights, something already previewed in court battles over who owns the content produced by today’s AI. Governments will try to implement doomed regulatory roadblocks, like those tried against cryptocurrencies. They will be even more hopeless this time, because, unlike crypto, AI applications do not need a decentralized structure, just a big server.

Scenarios

There are really only two ways the “AI revolution” can end. In the first scenario, unprecedented and unmanageable levels of unemployment will fuel poverty and public anger, in turn exploding into violence and destruction. Eventually, this will precipitate the ascent of an extremist populist leader who promises to make things better, but ends up making them much worse. One can imagine such a leader uniting a desperate population for a neo-Luddite “war against the machines” – destroying or banning “good” tech along with the bad, and plunging society into an economic, social and technological Dark Age.

The second scenario sounds less like a dystopian Hollywood blockbuster but is more likely, given the “solutions” that governments now have at their disposal and have been known to use in times of economic turmoil. This path involves timely state intervention and the implementation of a universal basic income – funded by extreme wealth redistribution, and powered by the political imperative to sustain both our fellow man and the machines that feed us. Any remaining producers, employers, property owners and value creators of any kind will have to support an unemployed and unemployable majority.