Scenarios for a ‘new normal’ in geopolitics

A period of globalization, prosperity and relative political calm since the end of the Cold War is over. What comes next is still in play.

In a nutshell

- A new era of conflict among great powers will likely last for a long time

- “Realists” and “liberals” disagree on the main issues driving geopolitics

- Transformative forces in the world will shape and define the “new normal”

The normalcy of the last three decades of post-Cold War globalization is gone. Now the questions are whether this period was an anomaly and what the “new normal” will be in the coming age.

Will it bring back the era of great power conflict as predicted by “realists” of international relations theory? Will globalization led by multinational institutions still prevail despite the great tragedy taking place right now in Ukraine? Who are the main actors and forces that will decide this outcome?

The realist world

Realists believe that the defining factors of international relations are states, their leaders and the system.

The system is defined by anarchy, the opposite of hierarchy. Anarchy means that there is no higher authority that ultimately decides conflicts among states. In an anarchic world, the survival of states is always under threat, requiring the acquisition of as much power as possible. The United Nations and other multilateral institutions matter little and change nothing. The only players that count are states, or to be more specific, the great powers and the mindset of their leaders who command their military and economic might.

Despite the underlying notion of anarchy, the realist world is orderly and simplistic.

In it, only two global superpowers, the United States and Russia, have the capacity to annihilate the world many times over. China and the European Union are already economic superpowers. Militarily, China rivals the U.S. in the Pacific and Europe is increasing its defense spending. Nothing and nobody can impose a military defeat or coerce a political choice on global superpowers.

With the addition of regional powers such as India, Japan, Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Iran, among others, global geopolitics is decided in the realist world and the balance of power among these countries defines international relations.

Realists suggest that Russia and China perceive the current global order as serving the interests of the U.S. and its allies. In response, Moscow and Beijing are trying to establish their own counterbalance. Besides Iran, the BRICS (Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa), Saudi Arabia and even NATO member Turkey are at odds with U.S. policies in varying degrees. Creating a counterbalance to the liberal hegemony could serve their interests, at least from the perspective of maintaining some freedom to maneuver.

More by Zorigt Dashdorj

Toward a different globalization

Realists argue that this balancing would take an orderly and less violent route through agreement on neutral “buffer” zones among the global superpowers. This would inevitably mean sacrificing the interests of some smaller nations, less globalization and the cessation of democracy promotion.

Or, alternatively, to counter the challenge, the U.S. and its allies will have to double down on military might, economic power and democracy promotion. Limiting rather than assisting the growth of its opponents, as was done through the late 2000s, is a crucial part of this thinking. This will mean tightly regulating market and technology access as part of a policy of strategic competition through containment. The third option is military conflict, through which a reordering of power would occur.

Those like John Mearsheimer, one of the more extreme examples of realists, have long suggested one such balancing act. He predicted that the U.S. post-Cold War liberal hegemony will not persist, and the smartest policy is to balance China by aligning with Russia. The argument is that it is not in the U.S. interest to encourage China’s growing economic might. Henry Kissinger, the ultimate realist who in the 1970s spearheaded U.S. rapprochement with China, called it unwise to “lump Russia and China together as an integral element.”

This camp blamed NATO expansion for pushing Russia into the arms of China, thus weakening America’s ability to contain Beijing. Russia viewed NATO enlargement as a security threat, despite reassurances. These realists say that the failure to achieve an orderly new balance of powers is the reason for the current war in Ukraine. In any case, the conflict of great powers has already started in Europe. This means the balance of power in Europe can only be determined on the battlefield until the sides are forced to negotiate, either through defeat or exhaustion.

The repercussions are felt globally. It is argued by realists that China is the biggest beneficiary of the conflict on the European continent as the U.S.-led alliance spends more of its resources and time on Europe and less on the Indo-Pacific. Also, it is argued that Russia acts as a buffer for China in its potential competition with the U.S.-led alliance. The view is that Beijing now is needed in the role of a peacemaker in Europe or at least as a neutral player. While all other great powers are bogged down in the war raging in Europe, China is quietly increasing its influence not only in its immediate neighborhood but globally.

Besides geopolitical fallout, the escalation into nuclear conflict is very real and it would be foolish to overlook its danger, something the proponents of the realist view caution constantly.

The liberal world

For those on the other side of the spectrum, defined as “liberals,” the multilateral institutions of the last three decades produced the greatest prosperity for humanity. Never has such a big portion of the world been elevated from poverty and the daily miseries of hunger, disease and social deprivation. The principles of a market economy, with some shades of industrial policy and government intervention, prevailed globally, with some exceptions. Even Russia and China, politically at odds with the U.S., conduct their economic policy broadly on market principles, most economists would argue.

Not only economic prosperity, but the most empowering ideals of human enlightenment are propelling this worldview. Humans are born free, and their rights are inherent, and the state’s only job is to protect them.

While democracy should not be imposed from outside by forceful measures, its superiority is unquestionable although government could be more efficient. The necessity of independence of the judiciary, freedom of expression and political competitiveness is not something that is questioned even by those who shy away from it in practice.

International relations have been served well by these principles and the institutions that promote them, such as the United Nations, World Bank, World Trade Organization and the International Monetary Fund. These institutions also need to be more efficient but should not be relegated to irrelevance. The Covid-19 pandemic has shown that the world would be a much more dangerous and fragile place without the coordination and knowledge-sharing by global institutions, liberals would argue.

New players will emerge on a global scale that are as influential as states.

The superiority of liberalism based on democracy, human rights and economic freedom is so dominant that even violent radicals and autocrats shape their discourse in terms of “freedoms” and “rights.” In this view, the current geopolitical divide is depicted mainly in terms of “democracy vs. totalitarian rule” and “freedom vs. oppression.”

For most of the last 30 years, the dominant view or hope among liberals was that the democratic path of development will prevail. South Korea, Taiwan and Indonesia are among shining examples of developing democracies.

The majority position has shifted visibly during the last decade. It is argued that those associated with nationalism, imperialism, totalitarianism and gangster-style kleptocracy oppose liberalism and want to destroy it. The goal of kleptocrats and autocrats in opposing this is to maintain domestic power and wipe out opposition in the name of sovereignty. Thus, no amount of “buffer” zones or any other form of balancing will stop their aggression because these rulers need a foreign enemy for domestic reasons to keep an iron grip on the population.

For proponents of the liberal worldview, appeasement that comes at the expense of the freedom of others is morally impossible. Those endangering, infringing and attacking the current global order can be contained until they collapse internally or are ultimately defeated if a conflict comes. The belief is that there can be no peaceful coexistence with those who want to destroy and dominate the free and democratic world.

This divide is much deeper than the geopolitical standoff in the realist world. The end game is not balancing, but the prevalence of one ideology over the other.

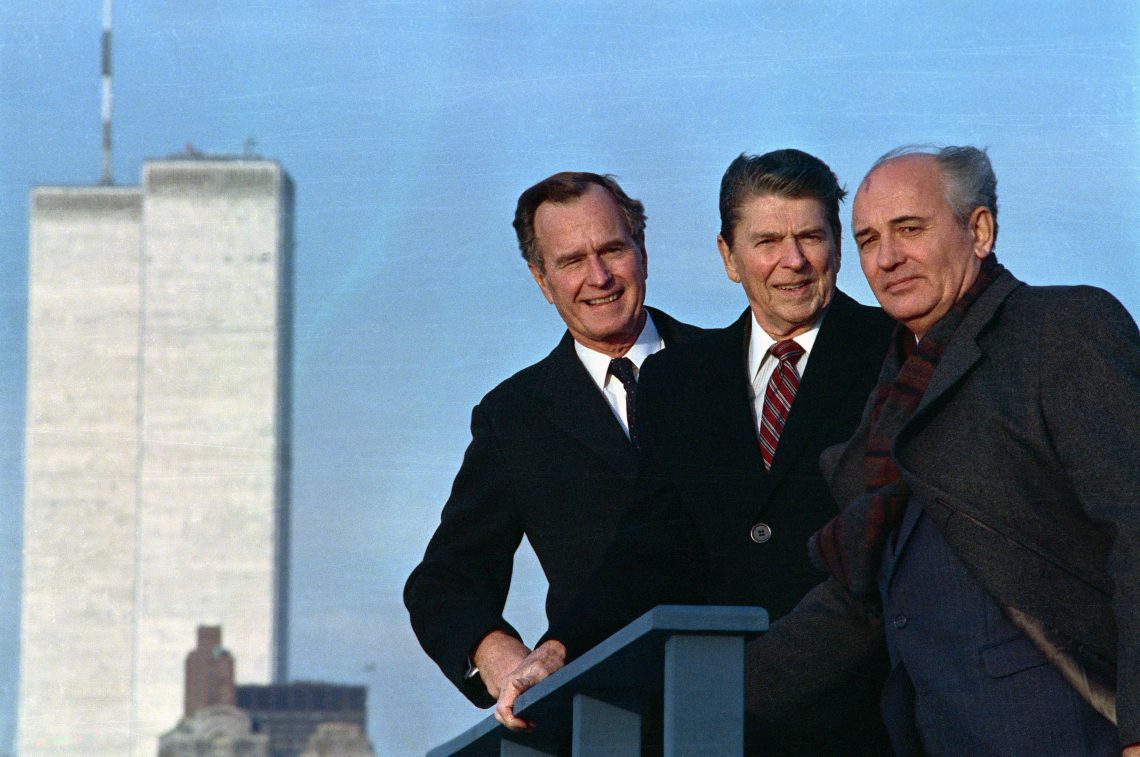

Leaders from a more hopeful era

Scenarios

In an October 2021 report for Geopolitical Intelligence Services, I suggested that the current situation is far more dangerous than the strategic stability of the Cold War era. The past was defined by the dominance of the U.S. and the Soviet Union in their own clearly demarcated spheres of influence in Europe. The threat of mutually assured destruction prevented a major war between the two opposing camps. Hence, intense competition didn’t spill out into a direct military conflict. Wars were on the fringes and between proxies.

Now, however, enlightened pacifism has given way to militaristic nationalism. Conventional arms are more prevalent and immensely destructive, even if nuclear weapons are never used. I suggested that diplomacy should act now to prevent a major war.

Now, Europe is already past the point of diplomacy amid a major armed conflict. Regardless of the underlying reason, all sides in Europe are settling in for a prolonged conflict even after the end of the tragic war in Ukraine. Europe perceives Russia as its primary threat and this perception may not change for decades.

Russia is in a much closer embrace with China, though the nations do not have a clear-cut military alliance yet. As one example, Central Asia has already been an arena of quiet contest between China and Russia, a sign that the interests of the two powers do not converge on all issues.

The conflict in the European theater means that the U.S. will increase its presence, including militarily, on the continent. The alliance with the U.S. guarantees security for Europe, thus limiting moves to stray far from U.S. policy, including toward China.

The U.S.-led alliance in the Indo-Pacific will dramatically grow its military capacity to balance China. The same buildup is surely to be expected from China.

Overall trade volume may not sink rapidly. However, much less interdependence in critical areas such as supply chains, technology and human exchanges is already becoming a reality. Most likely, it will not mean a complete “curtain” dividing the competing camps but rather the dismantling of “one-sided dependencies,” as German Chancellor Olaf Scholz has described. This approach is also called “de-risking” in sensitive areas.

Overall, the best outcome will be “competition not conflict.” A potential for armed conflict always exists if the powers don’t engage in careful diplomacy. It has already happened in Europe and could between China and the U.S. The triggers could vary.

With Russia’s war on Ukraine, the perception is reinforced that the only way to prevent another conflict is to impress the opposite side with a show of strength and the inevitability of unbearable harm. An uncontrollable arms race creates risks of an accidental war. A world packed with weapons is simply more dangerous than one with fewer weapons.

While in the West the current geopolitical divide is depicted mainly in terms of “democracy vs. totalitarian rule,” “freedom vs. oppression,” China, Russia and others view the West through the prism of “one-sided civilizational values.” This siege mentality fuels the perception that both sides are fighting for their survival and the other side is bent on destroying it.

The role of diplomacy, therefore, is in attempting to create lines of communication to prevent these triggers from being pulled. Diplomacy is the art of peace. Additionally, there are new forces in play that could make these traditional theories obsolete.

A confrontation, let alone a war, is not only a mobilization of resources but also of public support. Fragmentation of opinions is likely to make prolonged support for any issue unlikely. However, official government institutions do not solely shape social narratives and hierarchies. They do not decide political outcomes as they did just a decade earlier. The current world is increasingly based on social networking platforms that perform these roles instead of governments, even in countries attempting to control them.

Prolonged social mobilization is unlikely to occur in support of any wars or conflicts. The wars in Vietnam waged by the U.S. and in Afghanistan by the Soviet Union are examples of when societies became disillusioned.

Only such issues as environmental degradation, nuclear annihilation and global pandemic will create the level of social unity required for common action. New players will emerge on a global scale that are as influential as states. Current decision-makers, therefore, might be playing the outdated games of “great powers” and “democracies vs. autocrats,” as the new world is being formed.