Georgia’s waning faith in its pro-Western orientation

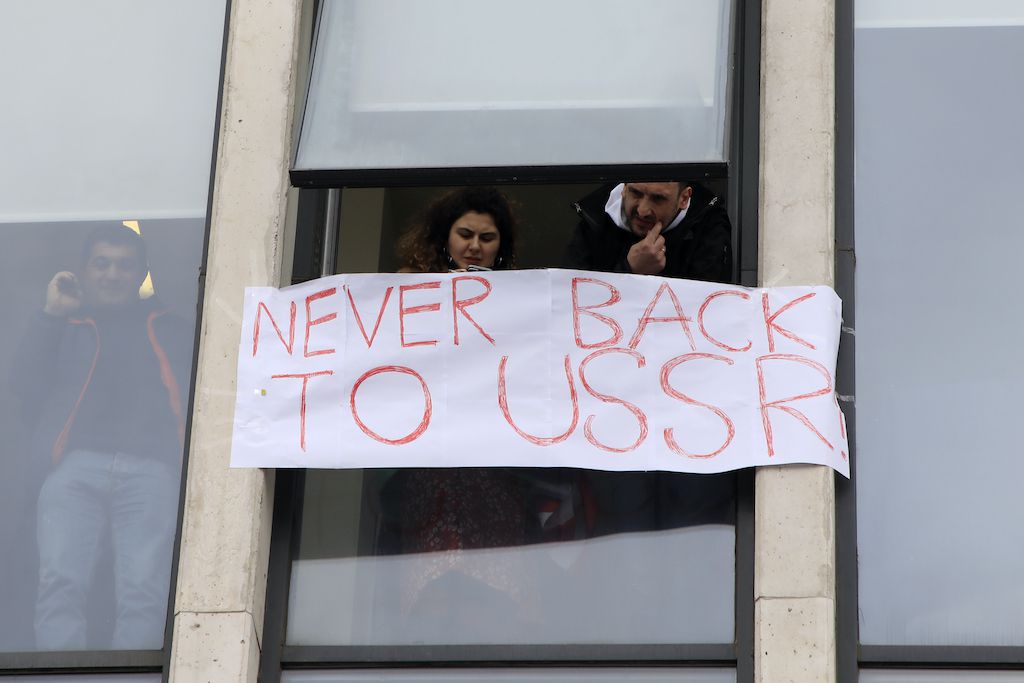

Ever since its Rose Revolution of 2003, Georgia has sought to embed itself firmly in the West but has made little progress toward joining NATO and the EU. While it resolutely keeps its distance from Russia, the country risks finding itself under the Kremlin’s influence once again.

In a nutshell

- The EU and NATO have lauded Georgia’s pro-Western aspirations but stopped short of accepting it as a member

- After two decades in the EU waiting room, Tbilisi’s resolve is beginning to falter

- The West, especially Europe, can ill afford to lose its resolute South Caucasus ally

Georgia is of strategic significance to the West, particularly Europe. Its location in the South Caucasus gives it military and transit significance, while its society endorses Western values more than any other in the region. The loss of this small but assertive ally would signal a weakening of Europe’s role in the region and as a global player. Unfortunately, there are signs that Georgia’s stubborn resolve to keep Russia at a distance and align itself more closely with the West has been weakening.

Small steps forward

The year 2008 brought two fateful events for Georgia, which by then had been laboring for five years to anchor itself in Western defense and economic structures and fulfill the dream of the Rose Revolution. These events produced one of the greatest paradoxes in the country’s modern history and determined the direction of its further development.

That year in April, NATO held a summit in Bucharest. Georgia and Ukraine had hoped to obtain Membership Action Plans (MAPs) fleshing out their paths to NATO membership. However, Russia’s pressure on Germany and, indirectly, France put the kibosh on the process. The two applicants were denied MAPs. It was one of the very few cases in NATO history where Berlin and Paris made a final decision, rather than Washington. Instead of solid road maps to membership, Georgia and Ukraine received vague promises.

Facts & figures

Georgia’s Rose Revolution

- It was the first of the “color revolutions” in the countries of the former Soviet Union during the early 21st century – massive street protests that led to the replacement of ruling elites; the next was the Orange Revolution in Ukraine.

- In December 2003, massive protests broke out in Georgia against the election machinations of President Eduard Shevardnadze.

- He was a legendary Soviet politician and diplomat, former foreign affairs minister of the empire, who had ruled the Georgian Soviet Republic since 1972. However, he failed to ensure the independence of his homeland, achieving neither territorial integrity, nor stable economic development, nor a pro-Western political orientation. His attempts to hold on to undivided power in Georgia prompted protests led by politicians previously associated with his camp: Mikheil Saakashvili and Nino Burjanadze.

- The Rose Revolution did not bring the anti-communist dissidents or new social leaders to power; the winners were young talent of the Shevardnadze team.

- The protesters’ key demand was a turnaround in Georgia’s geopolitical orientation – opening to the West, the European Union and NATO. This reflected Georgians’ historical ideas about their place on the world map. The new government, led by Mikheil Saakashvili, introduced such a change.

Source: GIS

However, the two fared better in another forum of Western states. In June of the same year, the European Council decided to establish the Eastern Partnership, a serious rapprochement process for six Eastern European countries, including Georgia. The same European states that blocked the enlargement of the Atlantic alliance were ready to move toward meeting Georgia’s nonmilitary geostrategic expectations.

The war

In August 2008, Russia invaded Georgia with overwhelming ground and air forces. The small Georgian Army acquitted itself well in what the author Ronald Asmus called the “Little War,” but, in the end, Russia prevailed and grabbed chunks of Georgia’s territory (in addition to Abkhazia and South Ossetia, “frozen” under Russian influence since the 1990s). The EU responded by accelerating the creation of the Eastern Partnership. Georgia found devoted allies among the freshly minted EU member states, mainly Poland and Lithuania.

Georgia took full advantage of the EU’s offer, and so did Ukraine and Moldova. The three countries signed Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Area (DCFTA) association agreements with the EU for free trade and visa-free travel.

Internal consensus

Mikheil “Misha” Saakashvili’s rule ended after two presidential terms in 2013. Enter Bidzina Ivanishvili, the business tycoon and founder of the Georgian Dream-Democratic Georgia (GD) party that won the 2012 parliamentary and 2013 presidential elections. Under subsequent governments, the country maintained its pro-European direction in foreign policy and undertook some systemic reforms. Mr. Saakashvili emigrated (fearing imprisonment on office abuse charges he dismissed as political revenge; indeed, in 2018, he was convicted in absentia) only to resurface in Ukraine after the 2014 revolution, and then was appointed regional governor by President Petro Poroshenko. His party, the United National Movement (UNM), has remained Georgia’s leading opposition force.

GD’s aggressive changes in the judicial system are seen as instruments for maintaining political power.

Of late, the Georgian issue has disappeared from the international political debate. The association agreement with the EU entered into force in 2014, providing the legal framework for Georgia’s closest rapprochement with Western institutions in the country’s history. Georgia also participates in NATO operations (some 80 percent of Georgian active-duty soldiers went through military missions abroad) and, in all respects, has been a tested ally of the West’s military arm.

The country does not maintain diplomatic relations with Russia, and as of today, none of its leading political forces seems ready to resume them. At the same time, Georgia’s relations with the EU have begun to sour.

The GD maintains significant support, especially among older generations and in the countryside. However, the party has been in charge for a very long time, and its opponents are mobilizing, particularly among younger citizens and big-city dwellers. And they have a grievance: GD’s aggressive changes in the judicial system are seen as instruments for maintaining political power.

Sings of trouble

European institutions criticized the changes. When the European Commission requested that Georgia roll back some aspects of the reforms before receiving more funding, the Georgian government withdrew from the loan deal. That was a surprising move, given the country’s precarious financial condition and the pro-European stance of most citizens. Tellingly, though, the confrontation did not dent support for the government.

The incident came as a surprise also because the Georgians cannot complain of a lack of understanding on the part of the president of the European Council, Charles Michel. He visited Tbilisi several times in recent months to mediate between the feuding political camps.

The loan termination was the first signal that the Georgian government might alter its European orientation. There are already doubts about whether the West can provide Georgia with the security and development opportunities it needs. Georgian experts echo such concerns inside and outside the country, given Washington’s diminished interest in the South Caucasus and Brussel’s silence on granting Georgia EU membership.

Before the Rose Revolution, Georgia’s foreign policy could be described as “multi-vectored.” Even after that period, when Georgia pivoted toward the West under Messrs. Saakashvili and Ivanishvili, China and two regional powers, Turkey and Iran, maintained their interest in the Caucasus country. Russia, despite its broken relations with Tbilisi, also remains in the game over Georgia’s strategic orientation.

If cautious skepticism prevails in the ruling party, a confrontation with Mr. Saakashvili’s camp will follow.

Rapprochement with the West touches a deep string of the “Georgian soul,” with its attachment to Christianity and longing for the splendors of old Georgian statehood. However, for the first time since 2004, an alternative multi-vector policy could also prove attractive if nicely presented. The thorny issue of cooperation with the West is in the background of many disputes in today’s Georgia, and government hesitation on this matter has become detectable.

On one hand, Georgia initiated closer cooperation with the Associated Trio: Georgia, Moldova and Ukraine, the Eastern Partnership countries that have signed association agreements with the EU. The Georgian government organized a conference on the matter in Batumi in July this year; many pro-European declarations were made. The tone was similarly positive during the numerous meetings with EU Council President Michel. On the other hand, the country rejected the strings attached to EU financial aid.

Within GD itself, there seems to be some controversy about shaping relations with the EU. If the option of cautious skepticism prevails in the ruling party, a confrontation with Mr. Saakashvili and his camp will inevitably follow. Such a conflict would be tactically favorable to the opposition and awkward for Mr. Ivanishvili’s party.

Domestic polarization

Even without an open dispute over the Union, the Georgian political scene is already growing more polarized. Until recently, low-level representatives of the government camp talked about co-opting new politicians from other factions, including the opposition. They hoped that the upcoming three years without major elections would allow for some domestic stabilization. However, a deepening divide is now more likely. Unexpectedly, the October 2, 2021, local elections – an event that usually does not attract much outside attention – turned out to be an important test of strength between the two camps.

The first round buoyed the ruling GD, which won 46.7 percent of the votes. The margin was significant, as the party had agreed at one point during Mr. Michel’s mediation to hold a new parliamentary election if it attracted less than 43 percent of the local elections vote. GD backtracked on this declaration later, but a result below that threshold would likely have prompted opposition demonstrations.

The UNM was not expected to do well but surprisingly managed to exceed 30 percent of the vote, securing the second rounds in many municipalities, including the capital, to be held on October 30. Former prime minister Giorgi Gakharia’s For Georgia party received 7.8 percent of the vote, and proposed trilateral talks with GD and UNM.

Mr. Saakashvili’s return to the country and subsequent imprisonment affected the elections’ outcome, energizing both his supporters and opponents. It is difficult to predict the short-term impact of the “Misha effect” on the political situation. The detained former leader will be a magnet for foreign media, and he will use every available pulpit to assail the government.

Scenarios

As a candidate for EU integration, Georgia’s assets are its strategic location, good international reputation and efficient lobbying. Its small size (3.9 million inhabitants) also helps its cause: larger entrants alter the political balance in the European club and strongly affect its distribution of benefits and costs.

The strategic risk for the West that Georgia will drop its pro-Western ambitions and settle for a marriage of convenience with Russia remains small. To prevent a change, the EU would need to send a clear political signal to Georgian society that EU membership is not a pipe dream, and the admission process could be accelerated. However, political rhetoric alone would not suffice. A new generation Eastern Partnership, based on close cooperation with the Associated Trio, including Georgia, could help keep Georgia firmly on its pro-European course.

The weak point of this scenario is Russia’s destabilizing influence and its ability to block Georgia’s ambitions in the international arena. Another problem is the stalemate in Ukraine. It is difficult to imagine Georgia’s path to NATO or the EU without Ukraine, a much larger country with more complicated problems. And finally, the Union suffers from an acute case of “enlargement fatigue” and faces cohesion problems caused by some new members.

The alternative for Georgia will be succumbing to the temptation of a multi-vector policy. Theoretically, it could bring new development opportunities based on cooperation with China or Turkey. Historically, such strategies of the Georgian state led to problems – such as rises in secessionist tendencies and “oligarchization” of the economy. In the end, they always exposed Georgia to Russian domination.

The author is convinced that the Kremlin envisions precisely such a scenario – Georgia’s return to the Russian sphere of influence under the guise of a multi-vector policy.

As in the case of Ukraine, this country’s political fate depends significantly on whether the West chooses to act or not. The likelihood that it does seems to be less than 50 percent now, but the situation remains fluid.