German exports slow down: Should Europe celebrate?

Higher labor costs in international trade may cause trouble for German exporters, but they are investing in new production facilities in low-cost countries. If German exports slow down, their market share might be taken by German producers outside of Germany.

In a nutshell

- Complaints about German productivity and savings have rightly been falling on deaf ears in Berlin

- German products are competitive, and this explains the country’s strong export performance

- Europeans had better worry about the future of German exports, which seem to have come under pressure

Blaming the Germans for their strong export performance has been a popular sport for years. According to the standard argument, a significant trade surplus signals that Germans save too much and, as a result, their domestic demand is relatively weak. If Germans consumed more, the reasoning goes, their imports from Europe would increase and benefit economic performance on the rest of the continent. This line of thought is flawed for a variety of reasons.

The details are beyond the purpose of this report, but one point should suffice. Higher savings translate into greater investments, not lower demand. This is exactly what characterizes the German economy. Companies in the European Union can only blame themselves if they are not able to attract German funds, or if German customers cannot find in the EU area what they need and would be willing to buy.

In fact, the German trade surplus shows that German products are competitive, and this explains the country’s strong export performance. At the same time, the euro is relatively weak: this provides an extra push to German exports and slows down imports. Hence, those who believe that German trade is “imbalanced” should argue that a more realistic exchange rate would be around $1.50 per euro (the current rate being some $1.16 per euro). One wonders whether the eurozone producers would celebrate a stronger euro and claim that the German “problem” was solved.

Subtle indicator

Complaints about German productivity and savings have been falling on deaf ears in Berlin, and rightly so. Competitive producers and prudent consumers do not pay much attention to those who argue that a Europe where competitiveness and trade imbalances are “harmonized” would be a better one. German Chancellor Angela Merkel hardly has time for speculating about what the equilibrium exchange rate of the euro should be, or for explaining to some European politicians why companies in their own countries perform relatively poorly.

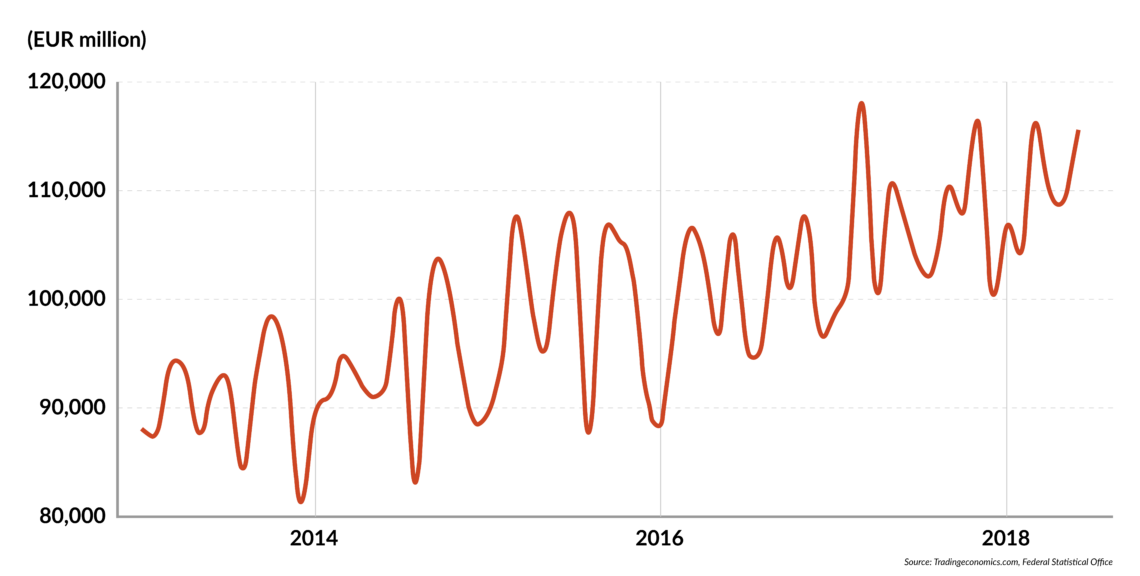

Rather than complaining about the export performance of German companies, the Europeans would do better to worry about the future of German exports, which seem under pressure. The data regarding the first quarter of 2018 shows that export flows declined by 1 percent – for the first time in eight years. One or two quarters are not enough to define a trend, and a 1 percent decline is not a great growth depressor. If such a trend sustained itself, Germany’s gross domestic product (GDP) growth would dip by some 0.3 percentage points on a yearly basis. Significant, but hardly devastating.

Facts & figures

German exports

2013-2018

Twin dangers

More importantly, one should consider that the drop in German exports comes at a time when growth estimates are being revised downward. While at the beginning of this year, GDP growth in Germany was expected to reach almost 3 percent, current forecasts predict a slower pace, between 2.1 percent and 2.3 percent. Two phenomena are causing this trend. First, the labor market is tight (the rate of unemployment in Germany is about 3.5 percent and youth unemployment about 6 percent), and producers find it increasingly difficult to find the workforce they need to expand production. Unless productivity and investments pick up considerably, hopes for future sustained growth significantly above 2.2 percent could be overoptimistic.

Secondly, since exports account for almost half of Germany’s production, it is evident that if the prospects for a full-scale trade war gather momentum, the German economy would be badly exposed. The auto industry is particularly vulnerable, but other sectors would also come under heavy pressure.

The export performance could indicate that German firms are paying more attention to meeting domestic consumption.

Germans will hardly perceive the slowdown. If exports stabilize (or grow at a slower pace) their economy will not shrink. What about the rest of the EU? The answer depends on how the two phenomena mentioned above – productivity and labor market conditions on the one hand, and the global trade crisis on the other – will play out in the future. Keeping this perspective in mind, two possible scenarios can be foreseen.

Implications for the EU

If productivity growth remains low and labor shortages are the primary constraints on German growth, a drop in exports is unlikely to be the consequence of weaker competitiveness. Since the data show that domestic demand and business sentiment are solid, the current export performance could indicate that German companies are paying more attention to meeting domestic consumption and investment demand, while holding market shares abroad.

If this view is correct, EU producers will find themselves under more pressure. For most EU economies, Germany is the leading export outlet. If German producers focus on the domestic market, European exports to Germany will suffer, and the economies for which Germany is a major outlet will feel the pain in terms of GDP growth rates. The shrinking German trade surplus would be bad news for many EU exporters, since few of them are currently in a position to challenge and replace the Germans in their traditional export markets. If the trend continues, therefore, we should expect lower growth throughout the EU.

Trade war threat

This is true for the short run. In the medium to long term, labor shortages in Germany will lead to a rise in the cost of labor, which might affect German competitiveness. Will this create chances for EU exporters? Not necessarily. German producers are already reacting to the consequences of a tight labor market by raising their investments abroad and thus increasing their production capacity in countries where the cost of labor is lower and regulations are less burdensome than in the EU. We can expect that future German exports will remain stable, while German imports from German producers outside of Germany will increase. Once again, EU producers will have little to celebrate.

What about the trade wars? It is no mystery that Germany has a lot to lose from a trade war with the United States. Vehicles are currently a significant source of revenue for German exporters, and although they may have profited from the recent strengthening of the dollar, further tensions with the American administration will be a reason for concern. Such worries deepen if one considers the rest of the EU, whose exporters are probably even more vulnerable to a trade war than Germany’s. German exports are of better quality, and thus well positioned to meet consumer demand even in the presence of higher tariff barriers.

German growth may accelerate, while many EU exporters to Germany will be outcompeted.

Moreover, Germany’s export structure has deep roots in China and fast-growing countries, which will likely turn for their imports to Germany, if their trade relations with the U.S. deteriorate. Finally, German producers have always been characterized by a clear commitment to developing their manufacturing outside of Germany. If trade wars remain local, the strategy of diversified foreign investments will pay off.

Scenarios

To summarize, if confirmed – and it is a big if – the past drop in German exports is not a real problem for Germany. It could mean, however, trouble for the rest of the EU – either because German companies will devote more attention to the domestic market and outcompete foreign rivals, or because it signals tensions in world trade, to which many EU countries are vulnerable.

In this situation, Europeans would be wise to watch how Germany will react to its labor shortages. If production costs in Germany rise, the rest of the old continent might find it easier to expand their exports, especially in sectors where prices matter most. However, in the medium to long run, German producers could react to higher labor costs by increasing their investments at home or outside the EU, and possibly enhancing productivity. If that happened, German growth would accelerate, while many EU exporters to Germany will be outcompeted.

A smaller German trade balance will not benefit companies located in the EU area. It will draw attention to a key lesson that many European policymakers so stubbornly fail to learn: a healthy performance by the German economy is good news for those who are positioned to meet German demand. German problems, though, quickly turn into a challenge for the rest of the Union – a challenge to which many countries are unable to respond, let alone exploit.