The slow death of Germany’s political center

The traditional mainstays of German politics have seen their bases move toward more radical movements. Although the SPD and the CDU/CSU have delivered great economic prosperity, voters punish them for immigration and high incomes.

In a nutshell

- The SPD and CDU/CSU are in decline

- New voters do not support the traditional parties

- More traditional voters believe these parties no longer represent their values

- A more fractious government could reduce Germany’s clout internationally

The October 2018 parliamentary elections in Bavaria were Germany’s most important political event since the previous autumn’s federal elections. The results confirm three long-term trends that are drastically changing the German political landscape: the decline of social democracy, the fragmentation of mainstream centrist parties on the left and right, and the increase of populist or identity-related voter motivations crowding out economic interests.

In many parts of Europe, but also in North and South America, similar trends can be observed. This report analyzes these trends and what they imply for the future of German politics.

Why Bavaria matters

As a “Freistaat” (free state), Bavaria insists on a special position within the federal structure of Germany. Most of that is symbolic, but since 1957 the state has been governed by a party that only participates in Bavarian elections: the Christian Social Union (CSU). In federal elections, the CSU allows its votes and seats to be added to those of the CDU group in the Bundestag (which itself does not run in Bavaria) and is rewarded with disproportionate powers in the federal government if the CDU/CSU is part of it. Currently, the CSU has three federal ministries under its aegis, including home affairs, led by controversial party leader Horst Seehofer.

Bavaria also stands out economically, as the most successful (non-city) state of Germany in terms of gross domestic product (GDP) per capita (46,000 euro), employment (the 2.7 percent unemployment rate indicates full employment), innovation and private investment (both foreign and domestic). It also scores at the very top in education.

Unsurprisingly, Bavaria has become very attractive for “foreigners.” Over the past 10 years, more than 1 million new people – mostly from other parts of Germany – have taken up residence in Bavaria. That number does not include the more than 1 million refugees and asylum seekers who have come to Germany since 2015 and mostly used Bavaria as a gateway for distribution throughout the country.

The migration crisis may have led traditional CSU voters to turn to the openly anti-migration AfD.

Both numbers had an impact on how the 7 million Bavarian votes (the 72.4 percent turnout was the highest since 1984) were cast. And both may be part of the explanation why the CSU lost its absolute majority of seats and 10.4 percentage points of the vote. The new Bavarian voters may not have adopted the tradition of supporting the CSU, and the state’s position at the frontier of the German migration crisis may have led traditional CSU voters to turn to the openly anti-migration party Alternative for Germany (AfD).

However, the AfD was not the big winner. With 10.2 percent, it received less of the Bavarian vote than it did during last year’s general election (12.4 percent). Since migration was hyped as the dominant issue of the election, it is remarkable that the AfD did not benefit.

The real winners were the pro-migration Greens. They doubled their share to 17.5 percent, and even became the strongest party in the Bavarian capital, Munich. This came largely at the expense of the biggest loser (both in absolute and relative terms), the Social Democrats, whose already record-low results of 2013 were more than halved. The SPD ended with 9.7 percent of the vote, in fifth place.

A mostly Bavarian niche party, the Free Voters, polled 11.6 percent. This conservative party is strongly rooted in local and rural areas and, like the CSU, advocates a restrictive migration policy. The most probable composition of a new Bavarian government will be a CSU/Free Voters coalition, which would allow current Minister-President Markus Soder to remain in power without making any significant changes to his policies.

So, is this much ado about nothing? Not quite. In many respects, the Bavarian elections confirm a trend that is very likely to shape the German (and European) political landscape.

Decline of the center-right?

GIS has analyzed the decline of social democracy in Germany and in other parts of Europe. The SPD’s 9.7 percent marks the party’s worst result in Bavaria since the 1930s, making the state the first where the party has fallen below the symbolic 10 percent threshold in recent history.

Compared to the steep decline of the center-left, the German center-right (CDU/CSU) is doing only relatively better. With about 30 percent support nationwide, it has slightly broadened its more than 10 percentage point lead over the SPD in postelection polls. Still, there is a clear trend showing that the center-right is also in decline. Where have the center-right CSU votes in Bavaria gone?

Facts & figures

Where they went

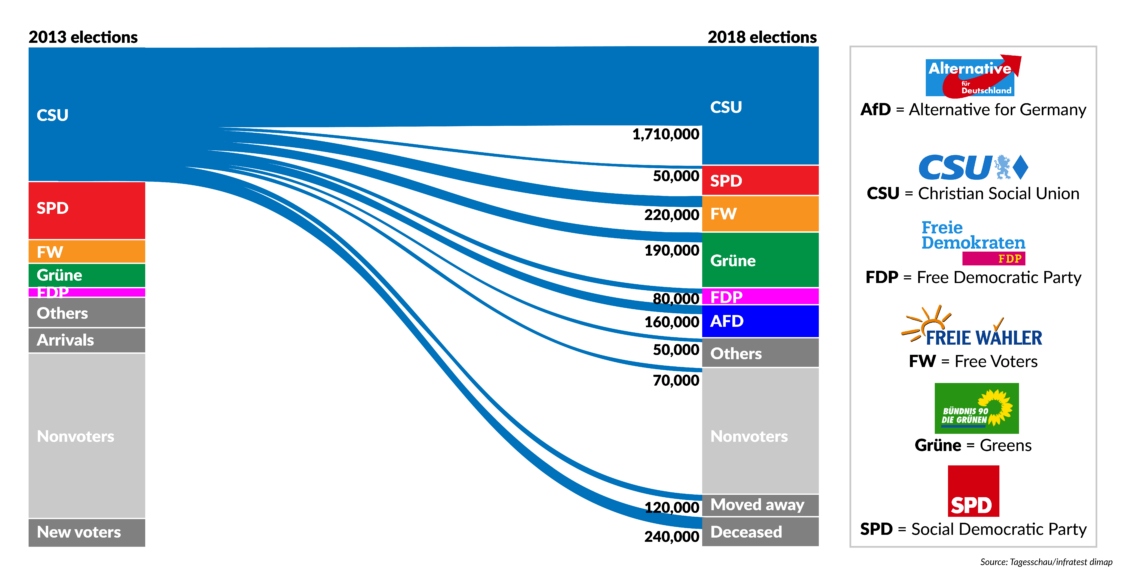

How those who voted for the CSU in 2013 voted in 2018

As the image above shows, the largest group of CSU “deserters” were the deceased. Some 240,000 Bavarians who voted for the CSU in 2013 were no longer alive to cast their ballot. The center-right (but also the center-left SPD) has a serious demographic problem: their loyal voters are simply dying out. Many other former supporters, especially the younger ones, have scattered in many directions: to the Free Voters, (a similarly conservative, but more grassroots, antiestablishment party) and to the populist-nationalist AfD, but also to the Greens, which in the Bavarian election presented themselves as a centrist, modern alternative to a CSU that was drifting too far to the right.

The center-right thus finds itself sandwiched between the parts of its traditional voter base that no longer see the party as embodying their conservative values (national homogeneity, sovereignty, security, stability, family, Christianity) and those who find exactly these conservative values to be no longer in line with “modernity” (multilateralism, multiculturalism, individualism). The center-left faces a similar dilemma: it must cater to its traditional social-conservative base while also embracing “modern” or “progressive” trends that motivate its younger members and party leaders far more than its traditional voters.

Fragmentation

Recent national polls give the parties of the “grand coalition” in Berlin (CDU, CSU and SPD) a combined support of just 40 percent. That compares to the 53.4 percent they received in the September 2017 federal elections, or to the collective 67.2 percent they polled in 2013. These numbers attest to Germany’s drift toward political fragmentation, with the traditional heavyweights CSU and SPD both losing heavily as the far-right AfD and left-liberal Greens rapidly gain ground.

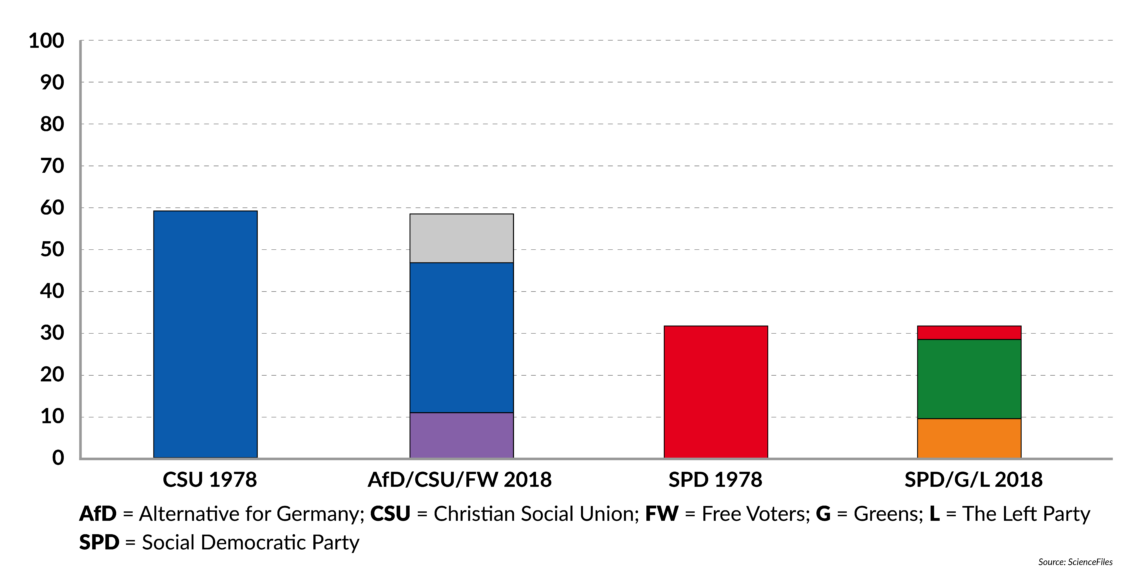

The Bavarian elections confirm that trend. If one compares the ideological divide between “right” and “left” 40 years ago to today, there has neither been a swing to the left nor to the right. What happened was a dramatic fragmentation within both blocs: whereas the CSU once monopolized the Bavarian right wing, it now must share it with the Free Voters and the radical AfD. The SPD gave up its dominance of the left to the Greens, while also losing votes and seats to the radical Left Party.

The more classically liberal Free Democratic Party (FDP) has been in and out of German parliaments and governments since then and cannot clearly be put in one of these blocs. It barely squeaked into the Bavarian parliament with 5.1 percent of the vote and may face similar struggles in the future.

Facts & figures

Bavaria: ideological blocs, 1978 and 2018

New motives

The rise of the AfD on the populist right and the strength of the populist Left Party (both mostly in eastern Germany) reflect a wider European phenomenon accompanying the decline of the mainstream centrist parties. Both ends of the political spectrum show significant overlaps in their positions against globalization and so-called “corrupt elites,” who are “betraying” the people. In Greece, Italy and France, these votes of no confidence can easily be attributed to worsening economic performance and political governance.

The case of Germany, and especially Bavaria, is different. After all, they are the envy of Europe in terms of economic prosperity and political stability. Yet the parties that have presided over this success do not seem to be getting any credit. Why?

The party’s left-wing narrative notwithstanding, Green voters belong to the elites in terms of education and income.

Yes, Germany’s mainstream parties are sandwiched between more committed stances and have often had to compromise as part of a grand coalition. But this does not explain the rise of the Greens, who have overtaken the SPD as the country’s second-largest political power not only in Bavaria, but in the rest of Germany as well (according to recent national polls). A look at where the Greens were most successful in Bavaria suggests a very different reason: their left-wing, “progressive” and “alternative” narrative notwithstanding, Green voters belong to the elites in terms of education and income. For the first time, the Greens won seats in Munich’s artsy, expensive districts, like Schwabing. They even scored well above average in one of Germany’s poshest towns, Starnberg.

Exactly opposite to protest voters on the populist right and left, most Green voters (rightly) see themselves as winners of globalization and open borders. Now that they have satisfied their basic economic and security needs, they are focused on more remote or “luxury” issues such as climate change, protection of endangered species, biological farming and bicycle lanes.

So, by delivering economic prosperity in Germany (and especially in Bavaria) – and bickering instead of boasting – the grand coalition may have become a victim of its own success. It has fed the Greens, whose voters feel most at ease with a virtue-signaling party in times of economic prosperity. They are happy to lodge a protest so long as their party is not in power at the federal level.

Consequently, the decline of both social democracy as represented by the SPD and of the center-right as represented by the CDU/CSU is likely to continue even in good times. The German proportional electoral system and socioeconomic trends make a seven-party Bundestag (Germany’s parliament) almost unavoidable. This also implies that new German governments will have to reach beyond a “grand coalition” of the traditional center-right and center-left. At local levels, such multiparty governments may more frequently be led by the Greens (as is already the case in another prosperous state, Baden-Wurttemberg). At the federal level, it is likely that no government can be formed without the CDU/CSU as the leading party.

Scenarios

So far, there is still no real upheaval in German politics. All parties are bracing themselves for the next electoral test: the October 28 elections in the state of Hesse. This is another wealthy part of Germany, currently governed by a CDU-led coalition with the Greens. Polls suggest the CDU could lose as much as a quarter of its support there. Though the SPD is in opposition in the state, it is also expected to suffer considerable losses – by as much as 20 percent. And again, both the Greens and the anti-migrant Alternative for Germany (AfD) are forecast to post strong gains.

This could mean that Germany’s federal government coalition may collapse less than a year after it was built. Chancellor Angela Merkel is under pressure from two sides: her own CDU/CSU and the SPD coalition partner. MPs from the CDU/CSU recently rebelled by ousting their parliamentary group leader, who was an ally of Ms. Merkel’s. The chancellor’s increasing loss of authority could lead to an unprecedented show of no-confidence when she seeks reelection as party leader this December.

However, it looks more likely that the SPD leadership will lose its nerve and bust up the grand coalition in a bid to shore up its already drastically diminished base. For obvious reasons, neither the CDU/CSU nor the SPD are keen to call snap elections now, since they both are polling at historical lows. But the German constitution allows (in fact strongly favors) building new governments based on the parliament as it is.

If the SPD abandons the coalition, Chancellor Merkel could try to build an alliance with the Greens and the FDP, a combination that failed to materialize despite long negotiations after last year’s general election. Alternatively, she could pursue a minority government and collect her majorities on a case-by-case basis. Chancellor Merkel has experience brokering deals on a wide spectrum of issues and ideological positions both in German and European politics. Since she intends to use her final years in power to present herself as someone who put integration (of Europe and of migrants) before party, the chancellor may find a minority government an attractive option.

In the longer-term perspective, however, such a move would neither help Ms. Merkel nor bring the centrist parties closer to solving their structural and strategic problems.

The situation will also hinder Germany’s ability to act in the international arena. One can expect forging compromises to become more cumbersome, with more parties wielding a potential veto. One can also expect more stagnation instead of leadership. What should not be expected are major German initiatives in Brussels or beyond, whether they concern Brexit, eurozone reform, European refugee policy or containing Russia.

Berlin will most likely become even more bogged down in domestic troubles, with little time, energy and capacity to address the big issues facing Europe and the world.