Focus Germany: Relations with China in perspective

Despite the need for a united EU stance on competition and security issues with China, Germany is focused on bilateral relations. By doing so, it gains a valuable trade partner, but it also incurs the risk of expanding China’s influence.

In a nutshell

- Despite the need for a united EU stance on China, Germany remains focused on bilateral relations

- By doing so, it gains a valuable trade partner, but it also incurs the risk of expanding China’s influence in the European sphere

- The only way for Berlin to solve this dilemma is to put long-term security interests ahead of short-term economic gains

GIS’s Focus Germany series examines key issues facing the European Union’s most crucial member and the continent’s economic powerhouse.

In recent years, German-Chinese relations have encompassed a broad range of competing interests: trade and investment obstacles; objections to China’s Belt and Road Initiative; rising concerns about China’s investments in Germany; Chinese cyber-espionage campaigns; and Xi Jinping’s nationalistic policies at home and abroad. The Federation of German Industries (BDI) has also published a critical position paper in which it declares China a “systemic competitor” both in terms of market economy and liberal democracy. Yet Germany is becoming more economically dependent on China than ever, threatening much-needed unity in approaches toward China within the European Union.

This past September, German Chancellor Angela Merkel made her 12th visit to Beijing, which took place against the backdrop of the China-U.S. trade conflict and continuing unrest in Hong Kong. Ms. Merkel was wary of criticizing the Beijing government publicly, and refrained from showing any solidarity with the demonstrators. She adopted a neutral position by calling for mutual dialogue and cooperation to peacefully settle the crisis.

Accompanied by a contingent of industry managers, the German delegation signed 11 economic agreements – a noteworthy development at a time when the German economy is suffering from the China-U.S. trade conflict, and the country’s automobile industry is still struggling with the diesel scandal and the transition to electric mobility.

Germany is becoming more economically dependent on China than ever.

Meanwhile, German Foreign Minister Heiko Maas had a short meeting in Berlin with a leading figure of the pro-democratic Hong Kong Demosisto movement, Joshua Wong. The Chinese government heavily criticized Mr. Maas and called in the German ambassador in Beijing to discuss the “negative impact on bilateral relations.” It was an attempt to warn Germany that this particular line ought not to be crossed.

The BDI perceives China both as an economic partner and a systemic competitor, and it calls for a more united and assertive EU stance on China. Currently, the German government aims for reciprocity in its dealings with China, instead of the one-sided cooperative approach of the past. From a political perspective, Berlin is beginning to view Beijing as a potential threat to international order, as shown by territorial claims in the South China Sea highlights.

Assertive Germany

The BDI is already calling for the EU member states to adopt a coherent policy, since no single country can cope with the economic and political challenges posed by China as a systemic competitor. So far, Germany has been betting on the West’s growing ties with China to lead to reforms and liberalization – “Wandel durch Handel,” or “change through trade.” Aided by the booming Chinese middle class, the country could theoretically be prompted to transform its political system into a Western-style democracy, like that of Taiwan. But history is seldom so straightforward, and these hopes have so far proven misplaced.

Under President Xi Jinping, China has gone down a “back to the future” path of increasingly nationalist domestic, economic and foreign policies. Political decision-making has once more become centralized, and previous reforms like separation of state and party or collective leadership have been abandoned. Instead, state interventions and the cult of personality have been revived. Unequal treatment, discrimination of public procurement, excessive state control, forced technology transfers and industrial espionage have undermined the trust of German companies in China. Beijing’s Made in China 2025 initiative for 10 key future industries (including electric mobility and batteries) has given rise to new challenges for the German industry.

The Chinese Communist Party now acts as a watchdog from within German and other foreign companies, which have to disclose sensitive data and restrict cross-border traffic since the Cybersecurity Act of 2017. The introduction of the Social Credit System and constant digital surveillance have created an Orwellian system of state control.

China does not observe the Western rule-based global order on which German governance relies, nor does it follow a win-win approach in its bilateral economic and political relations. Instead, it deliberately plays one EU member state against another (like with its “17+1” forum, which includes only certain EU countries). All of these policies are fundamentally at odds with German interests.

Facts & figures

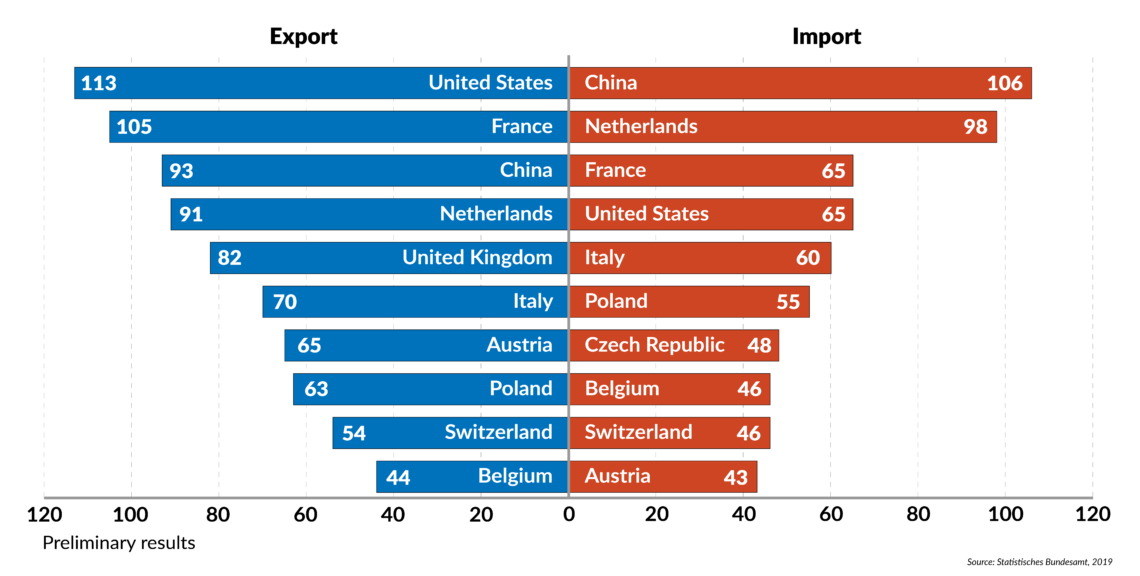

Germany's major trading partners, 2018

in billions of euro

Germany is aware of China’s long-term investment strategies for acquiring patents and valuable technology assets. The unexpected acquisition of a 10 percent share of Daimler AG by Geely Automobile Holding Co Ltd at the beginning of 2018 caused major uproar – particularly since Chinese media admitted that Daimler’s battery technology for electric cars will “support the growth of the Chinese auto industry.” Geely circumvented strict German disclosure rules with a cleverly-engineered combination of derivatives, bank financing and share options to exploit legislative gray areas.

In 2016, the Chinese appliance maker Midea bought Kuka, Germany’s largest producer of industrial robots. This highlighted the vulnerability of innovative small- and medium-sized tech companies – the backbone of Germany’s economy. In February 2017, the Chinese conglomerate HNA Group was able to buy into Deutsche Bank despite HNA’s hazy ownership structure. (HNA Group has also bought a majority stake in the small Frankfurt-Hahn airport for unclear purposes.)

Germany reacted by changing its foreign investment law and reducing its 25 percent threshold to 10 percent for non-European investments in “critical infrastructure” and high-tech industries. The new investment screening framework also allows four months instead of two for the government to investigate whether takeovers endanger public order and national security. China criticized these new protectionist policies, but they are in line with a global backlash against Chinese takeovers.

Earlier, the German government had already blocked an attempt by the State Grid of China to purchase a 20 percent stake in the German electricity grid operator 50Hertz. It also prevented the acquisition of the German company Leifeld Metal Spinning, a machine tool manufacturer that specializes in high-strength materials for the aerospace and the nuclear industry.

Berlin will want a strong and united EU policy aligned with its own, especially since German leverage against Beijing is weakening. This could go hand in hand with a stronger EU foreign and security policy in Asia; an EU naval fleet could travel through the South China Sea and Taiwan Strait to demonstrate its strategic interest in regional stability and freedom of navigation – all the more so since 90 percent of its trade with Asia transits through this maritime region.

Kowtowing to China

Chancellor Merkel’s recent visit to Beijing has clearly highlighted Germany’s growing economic dependence on China. German companies have expanded their exports by 10 percent, up to 93 billion euros in 2018 compared with 2017. China may become Germany’s largest export destination in a few years, although the U.S., France, the United Kingdom and the Netherlands still outrank it for now. But China is already the largest source of German imports, making it a crucial trading partner.

In 2018, German direct investment in China amounted to around 80 billion euros, roughly 7 percent of its total foreign investment. Some 6,000 German companies and more than one million employees are active in China. For German industry, China is no longer a production hub, but rather an important research and development partner, notably in digitalization and industrial artificial intelligence (AI).

Groveling will lead to increasingly problematic demands for Western companies and governments.

Despite the BDI’s growing concerns about China’s assertive nationalistic policies and unwillingness to accept a common playing field based on the rules of the World Trade Organization, it does not favor containment or disengagement. Instead, the German industry supports a cohesive EU policy toward China.

Meanwhile, the German government has been hindering rather than pursuing such a policy. Unlike Berlin, French President Emmanuel Macron has taken steps to create a united front. For example, he invited European Commission President Jean-Claude Juncker and Ms. Merkel to his summit with President Xi Jinping in Paris. In comparison, the German chancellor’s back-to-business approach of expanding unilateral German business interests is weakening the EU’s leverage in the view of Paris and others – a state of affairs that China will further exploit.

While Germany and the EU have recognized the threat to European values posed by Chinese competition and its authoritarian model, Germany may prove unwilling to sacrifice its economic interests for the sake of a unified EU policy toward China.

In this scenario, tendencies of “preemptive obedience” and self-censorship in dealings with Beijing might intensify within the EU, thus spreading political influence and nondemocratic values in Germany and Europe. This threat will be particularly salient if Germany faces economic problems. China would then be able to apply its divide-and-rule tactics even more successfully, thus potentially also destabilizing NATO and transatlantic ties.

The BDI’s strategic position is already being undermined by companies. The official apology of the previous Daimler CEO Dieter Zetsche in February 2018 was an obvious example of kowtowing to Beijing. His marketing department had quoted the Dalai Lama in an Instagram post promoting Mercedes-Benz, prompting Chinese social media users and official state media to roundly condemn the company, which sells some 30 percent of the cars it produces to the Chinese market. In contrast to other CEOs, the company not only removed the post, but also wrote an official letter of apology.

Chinese leaders have no respect for weakness. The inevitable outcome of groveling will be increasingly problematic demands for Western companies and governments when it comes to Chinese interests and values. In this situation, Germany would also back away from a stronger EU security presence in East Asia.

Strategic perspectives

Germany and the EU are now faced with an increasingly self-confident China. This implies competing with China’s geoeconomic interests and geopolitical objectives, including Beijing’s promotion of its authoritarian model, values and normative power.

The most likely short-term scenario is that Germany’s bilateral relations with China will remain highly ambivalent. The more economic problems Germany faces, the more willing it might be to compromise its long-term strategic interests in exchange for immediate trade and economic benefits.

The more economic problems Germany faces, the more willing it might be to compromise its long-term interests.

However, Germany and the EU might come to realize that the economic challenge posed by China is part of a broader systemic clash. Beijing’s trade and investment policies cannot be separated from its nationalistic and authoritarian governance, which challenges the democratic foundations of Germany and the EU.

From a longer-term perspective, Germany – as the largest and most economically powerful EU country – will seek to preserve its strategic interests through the EU’s economic, foreign and security policies. More and more, it will understand that it cannot maintain special economic relations with Beijing at the expense of other EU member states.