Pandemic opens the door for an Italian conservative

Italian politics has been reshaped by the coronavirus. Dissatisfaction with the populist star Matteo Salvini has meant an opportunity for a new rising figure, Giorgia Meloni. As the government struggles with pandemic politics, Ms. Meloni is angling to be the next big thing.

In a nutshell

- Party leader Giorgia Meloni is seizing the crisis

- A more serious tone is in demand in Italy

- The populist Lega’s support has declined

The coronavirus has caused major changes to the vocabulary of politics all over the world. With the rising case counts and death toll, leaders have shifted to a more serious tone. Parties have replaced traditional interlocutors with scientists and experts, seeking to cast their arguments to voters as reasoned and thoughtful.

In Italy, Covid-19 certainly added to the problems of Matteo Salvini, leader of Lega, the largest right-wing populist party. It also, albeit indirectly, contributed to the rise of Giorgia Meloni – head of a smaller but growing right-wing populist party, and now a contender to lead the entire Italian right-of-center coalition.

This dynamic is neither unexpected nor wholly new. Populism is sometimes simply the first stage in the life of a party or a movement, before it becomes more fully institutionalized. All new parties are populist, insofar as they are waging war on the existent political establishment, thus appealing to outsiders. Once in government, their language predictably changes.

Something similar may happen with their leaders. Political leaders, like business leaders, are not necessarily for all seasons; the kind of leadership right for a start-up may not be the best to grow a company’s market share. In particular, the more a party grows, the more necessary that it appeals to the marginal centrist voter.

Fading star

In this momentous phase of Italy’s political life, as the country surpasses France and Iran for deaths due to Covid-19, Mr. Salvini’s language may be out of touch with public opinion. During the first lockdown, in the spring of 2020, Italians rallied around the flag and supported the government of Prime Minister Giuseppe Conte in its fight against the pandemic. But times have changed. Protests have erupted as the Conte government has engineered a series of regional lockdowns, segmenting Italy in different areas based upon technical risk parameters.

Self-employed people and those working in retail are particularly affected. With tourism collapsing and restaurants mandated to close for dinner, it is small businesses – generally considered the backbone of the Italian economy – that have suffered the most financially. And when people are in dire straits, their political demands tend to change.

Is Matteo Salvini’s leadership rising to the unique dynamics of the pandemic?

Over the last several years, Mr. Salvini’s momentous rise to the top of Italian politics was primarily fueled by identity politics and the perceived threat of illegal immigration. His success was based on his formidable ability to act as a sounding board for what his typical voter might say in casual conversation with a barista over his morning cappuccino. In 2013, when he took over as the leader of Lega Nord— which rebranded as simply “Lega” five years later — the party was credited with some four percent of the vote; by the 2019 European elections, the party had reached 34 percent. His success was indisputable, grounded in an aggressive communications strategy and an intense, boots-on-the-ground campaign.

But is that political style – and Matteo Salvini’s leadership – rising to the unique dynamics of the pandemic? Recent polls have ranked him third among the most popular Italian leaders, considered credible by 34 percent of those interviewed. Above him comes Prime Minister Conte, once supported by Lega (together with the Five Star Movement) and now the pivotal figure of a left-of-center coalition. But the top of the list is claimed by Giorgia Meloni, supported by 38 percent of those polled. Leaders go up and down in the polls, but her approval rates have been steadily on the rise for the last two years.

Deep roots

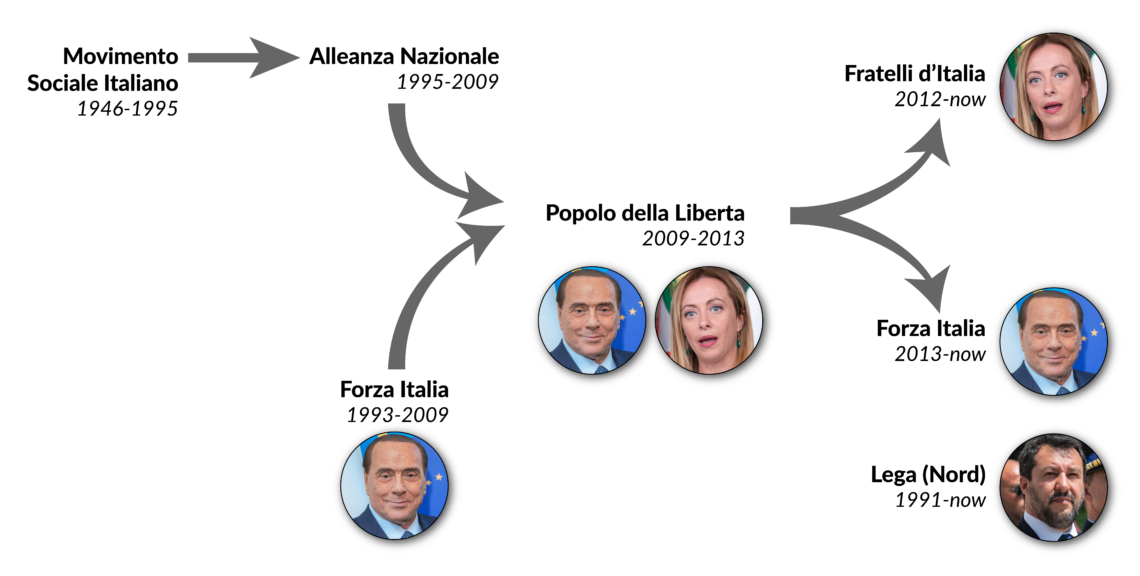

Ms. Meloni is the leader of Fratelli d’Italia (FdI), or the “Brothers of Italy.” Her party is the result of a secession from the former Popolo della Liberta (PdL), which was itself formed by the merger of former prime minister Silvio Berlusconi’s Forza Italia and the Alleanza Nazionale, the more liberal evolution of the traditional post-fascist Movimento Sociale Italiano (MSI). That merger proved unstable when Mr. Berlusconi resigned from the prime minister’s office, paving the way for a caretaker government led by economist Mario Monti. The faction that would become the FdI resented the partnership forged by Mr. Monti with German Chancellor Angela Merkel, and considered their austerity measures, however bland, a threat to Italian sovereignty.

Facts & figures

By leaving the more centrist PdL, Ms. Meloni resurrected the traditional network and ideological rhetoric of the Italian right-wing. That tradition is quite different from both Christian Democracy, the dominant strand of right-of-center politics in continental Europe, and from the kind of Thatcherism to which Anglo-Saxon conservatives have at least paid lip service.

The MSI, which dates back to 1946, was more socially oriented and tended to claim the “respectable” legacy of fascism. This was not as much in reverence for the persona of Benito Mussolini (who is still popular among some fringe extremists) but for the alleged “modernity” of fascism: one which consisted largely in anticipating some of the core institutions of a modern welfare state. The Mussolini regime regulated businesses, introduced healthcare and public health measures, curbed the rights of businesses to fire employees, promoted a version of social insurance and, in the 1930s, nationalized banks and businesses. Not surprisingly, after World War II, the extreme right – which was excluded from any governing coalition until the rise of Mr. Berlusconi – found its support mainly in the country’s south, where public employment is king, rather than from enterprising northern businessmen.

Adaptation

For this reason, when Ms. Meloni quit the PdL to establish the smaller FdI party, a partnership with Matteo Salvini seemed natural and relatively harmless for both. The former appealed more to southerners than northerners, and the latter the opposite. The two campaigned like good allies, with the FdI growing more slowly than Lega but substantially sharing its campaign messages and slogans. They both railed against European technocrats and drew on the fear-inducing correlation, however shaky, between immigration and crime. The FdI leader developed her public persona and support base, but at a much slower pace than Mr. Salvini, who sounded bolder and newer and lacked the heavy baggage of post-fascism.

Why then is Ms. Meloni suddenly on the rise? Neither of the two is strictly a “new” politician. The Lega chief started his political career in 1993, one year before Silvio Berlusconi, then a young man in the city council of Milan. He had been an activist, a journalist in Lega’s newspaper La Padania, then, beginning in 2004, a member of the European Parliament. Giorgia Meloni, meanwhile, is younger, and entered local Rome politics only in 1998. But she was an earlier achiever, serving as deputy chairperson of the parliament’s house since 2006 and from 2008-2011 as minister of youth in the Berlusconi government.

This national prominence and the association with then-Prime Minister Berlusconi may have made it more difficult for her to appear as an independent political leader. Indeed, being a minister under Mr. Berlusconi has hardly been a blessing for a whole generation of forty-something, right-of-center politicians, who appeared “old” and “corrupt” just as the Five Star Movement was on the rise.

But fortune favors the persistent. Giorgia Meloni kept at it, and carved out for herself a more nuanced public persona than “Il Capitano.” She is equally good at yelling in squares and public meetings, but is a more accomplished parliamentary speaker. She is no less critical of the European Union than Mr. Salvini, but unlike him has never openly endorsed proposals to quit the euro. In particular, she cultivated international relationships, to such an extent that she was elected president of the European Conservatives and Reformists (a European Parliament group comprising right-wing parties from fifteen member states, including the Swedish Democrats and Spain’s Vox). She has even developed ties with Republican groups in the United States, and took part in the “National Conservatism Conference” hosted in Rome by the Edmund Burke Foundation, a group close to neo-nationalist theorist Yoram Hazony.

It is too early to tell if Meloni will be a more legitimate contender for prime minister than the previous rising star.

Ms. Meloni speaks English better than most Italian politicians, and, unlike many, she seems to value international regard for her party. In the European Parliament, Mr. Salvini’s Lega shares the benches with the French National Rally in the Identity and Democracy group. He was credited with an interest in ties to Russian President Vladimir Putin, and several years ago some of his closest collaborators were alleged to work as liaisons between the two. Giorgia Meloni has instead insisted on placing herself firmly on the side of the U.S., a more reassuring posture for potential allies and supporters.

However, international success may breed domestic problems. During the pandemic, the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) stated that “the current health crisis should not be exploited as an opportunity to establish an even more centralized Europe. The ECR opposes centralist Brussels impositions, and believes that the EU should be more flexible and respectful of the prerogatives of the different countries.” Conversely, Italy rejoices at transfers within the Next Generation EU program, and both the FdI and Lega tend to want more of these transfers, not fewer. How will she reconcile her positions in Italy with those of her allies in Brussels?

Electoral chances

The regional elections in September 2020 were a setback for Italian right-wingers, the pandemic predicament essentially reinforcing the position of standing regional leaders. The right did not win, as many feared (or hoped), in Tuscany, where the left has reigned without interruption since World War II, nor in Campania or Puglia, although the latter appeared more within reach.

Still, even if Italians tend to vote for the devil they know, avoiding a change of captain during a storm, they did shift to the right in the Marche region, where the candidate of the center-right coalition was of Ms. Meloni’s choosing. This is not a major change, but it did help her score a small victory and avoid the reputation of picking the wrong candidates – as was inevitable for the bigger fish in the coalition. Matteo Salvini will be blamed for having lost the last two rounds of regional elections, while Luca Zaia, a Lega governor who won by a landslide in Veneto, is now being called by the press as a possible contender for the party’s leadership.

Outlook

In the last few months, as she forcefully criticized the management of the pandemic by the Conte government, the FdI leader has struck a more pro-business tone. Though her party is rooted in the tradition of right-wing corporatism, and while she herself has no passion for Thatcher-style conservatism, Ms. Meloni has been smart enough to try to channel the demands that businesses have expressed. Indeed, there was a vacuum to fill: the establishment-left Partito Democratico has moved even further leftward, while the more centrist Forza Italia (still led by Silvio Berlusconi) is weaker and thus less appealing to businesses that need prompt measures to deal with the crisis.

When elections do arrive, it is too early to tell if Ms. Meloni will be a more legitimate contender for the prime minister’s office than the previous rising star. With her coalition partners, she holds significant weaknesses. She is a prima donna in a party of lesser figures, in which the number of reliable advisors or prospective ministers can be counted on one hand. But unlike Matteo Salvini, she has increasingly presented herself as a grown-up. Serious times call for serious people; Giorgia Meloni’s bet is that she can be one, and still hold on to her populist base.