Dark clouds gathering over the global economy

We are probably coming to the end of a global economic recovery. But with interest rates still hovering around zero, central banks will have no ammunition to fight a recession. Meanwhile, debt is high and more trade barriers are going up. The underlying causes in imbalances of global economy must be addressed.

Typical economic cycles last about seven years. Since the 2008 financial crisis, we have seen continuous growth in the global economy, and more is expected. The International Monetary Fund forecasts global growth of 3.9 percent for this year and next. We would like to believe that these are realistic predictions and not wishful thinking.

The issue is whether the recovery and the expected growth have a robust, sustainable basis – or are substantial caveats appropriate?

The growth in recent years has been largely driven by consumption. Unfortunately, this was, to a non-negligible extent, due to abundant consumer and housing credit based on cheap money, provided by the central banks in nearly all major economies. At the same time, most governments did not take the opportunity to reduce their deficits, but continued high levels of spending and increasing their countries’ debt.

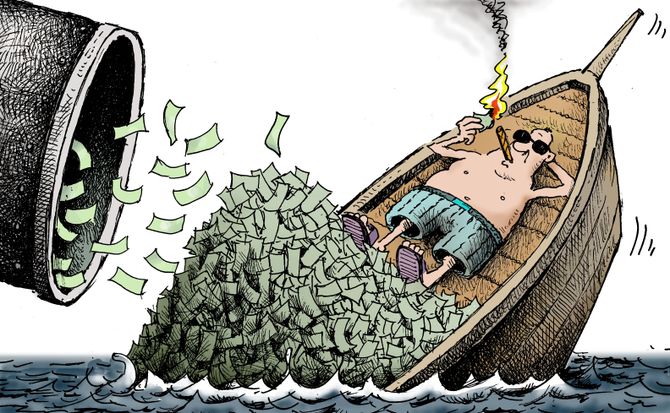

The cheap-money drug

All major central banks arrived at the limit of their ability to reduce interest rates (being already near zero or below) and have begun to talk of “tapering.” The United States Federal Reserve has already started, while the European Central Bank announced its more than 2.6 trillion-euro bond-buying program would end in September. Believing in the magic that some 2 percent inflation enhances growth, the officials at the ECB have concluded that this goal has finally been reached, so they can also slowly increase interest rates.

However, there are two problems: First, even if we believe in the 2 percent magic, this figure is mainly driven by an increase of 8 percent in energy prices and some 3 percent in food prices. Significantly, core inflation rose by just 1 percent.

But what really aggravates the situation is this: an economy that grows mainly due to abundant, cheap money is a bit like a drug addict. It cannot function without additional money supply – it always needs more, or else it collapses.

The world is arriving at the possible end of a growth cycle, while households and governments have not just empty pockets, but also a high debt burden. At the same time, the central banks have used up all their ammunition. The necessary and overdue increase in interest rates will be disastrous for budgets, both public and private.

Treating the symptoms

The history of the last quarter century’s fiscal and monetary policies mainly consists of treating symptoms, and less so the underlying causes of economic imbalances. If we look at the world’s financial mechanisms, we can see that they are built to avoid situations that can trigger a crisis, but lack the courage to implement real corrective measures. These could be painful, and would expose fundamental weaknesses that are less due to market conditions than significant political “manipulation” of the economy. Some of the main problems have been populist overspending, too much government involvement in the economy and excessive intervention in markets and business.

The recent increase in oil prices could be a real threat to growth. Cheap energy is a good economic driver. The rise might have initially been welcomed as boosting inflation, a sign expected by central bankers, but the increase in costs creates a braking effect. OPEC was aware of this phenomenon and decided to increase output to stabilize prices. The White House also strongly urged such action. It is concerned about the adverse impact of higher energy prices on a fragile world economy (and not only in the context of its new sanctions on Iran).

It may be necessary to introduce a long overdue open debate, with the objective of freeing trade from restrictions.

For a long time, a big problem has been protectionism. The public was not too aware of this issue until President Donald Trump, in his usual very direct way, started to retaliate against unfair practices by a number of U.S. trade partners, especially China. However, even Western blocs, including the U.S. and even more so the European Union, are not innocent. Protectionist policies have not only used tariffs as political tools, but also introduced quotas, regulatory barriers, product specifications, foreign-exchange policies, subsidies and investment restrictions. They put up layers of bureaucratic red tape and numerous other obstacles.

The U.S.’s current retaliation has certainly not created the problem, but it could trigger a crisis. It may be necessary to introduce a long overdue open debate, with the objective of freeing trade from these restrictions. Unfortunately, protectionism under the pretext of shielding consumers or securing jobs is popular, and therefore a valuable tool for populist politics. Such measures are applied – to the detriment of prosperity – in authoritarian countries and in democracies alike.

A combination of rising energy prices, trade restrictions and slowing growth in certain countries (especially China), are adverse indicators for the world economy. The staggering debt of both governments and households allow little margin for additional consumption. Due to quantitative easing and low interest rates, central banks will not have room to head off a strong recession. We have to recognize that already, central banks’ balance sheets are overextended.

And although we should also not overestimate them, political misjudgments and crises are adding to the problem. We need not panic, but it is time to make a cautious, critical assessment and not be misguided by false hope.

It is time that the real causes are treated, and not just the symptoms.