Venezuela nears the breaking point

What will happen to Venezuela after the government tries to steal an unconstitutional presidential election on May 20? Everything depends on the cohesion of the splintered opposition and the determination of the international community.

In a nutshell

- As Venezuela’s economy collapses, a $50 billion default and refugee crisis loom

- Only an internationally mediated, peaceful transition can head off a humanitarian crisis

- Cuba’s participation could make the difference between failure and success

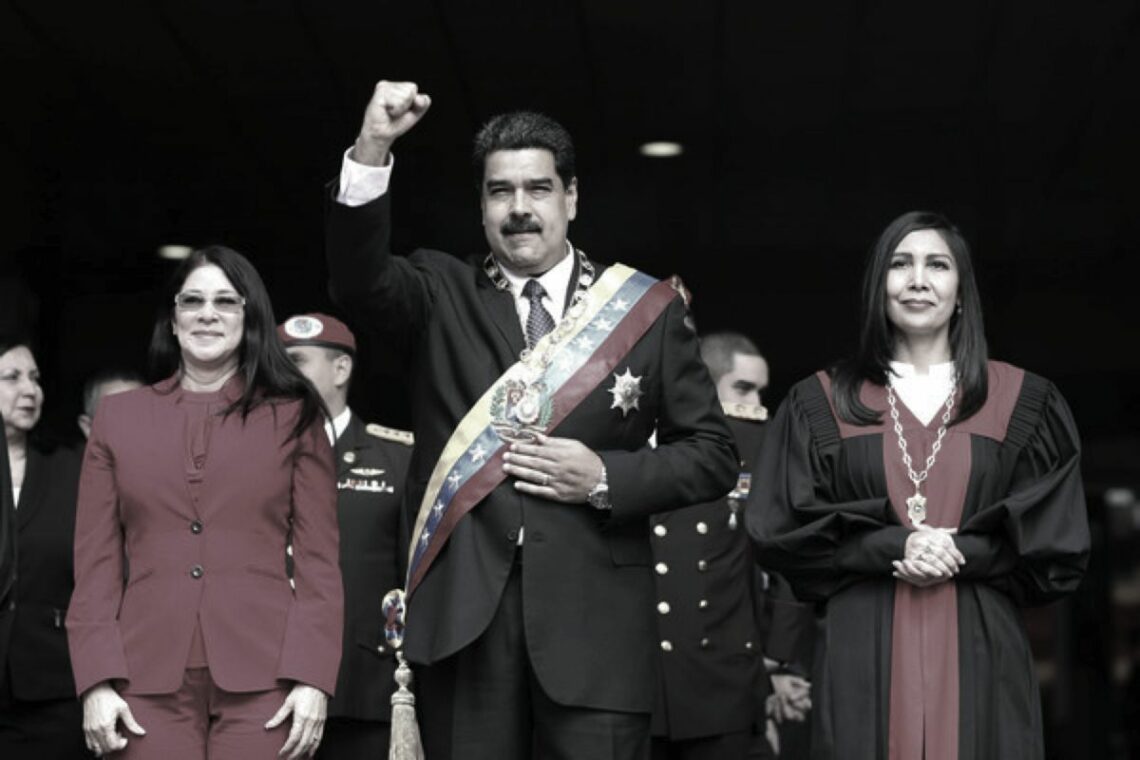

The government of Nicolas Maduro has declared May 20 as the date of the next presidential elections. The announcement was met with harsh criticism from the domestic political opposition led by the Democratic Unity Roundtable (MUD) and from international actors – especially the Lima Group, which is monitoring the situation in Venezuela on behalf of more than a dozen countries in Latin America and Canada. The United States, which already had placed sanctions on more than a dozen Venezuelan officials, also denounced the move, imposed more sanctions on government leaders and said a military option “was on the table.”

Moving the presidential elections up five months, to May 20, violates Venezuelan law, which stipulates that elections must be announced six months in advance. It also gives Mr. Maduro, the incumbent, a number of insuperable advantages.

The opposition will have little time to mobilize or put together an organization to monitor the polls; the government says it will invite international observers, but it is unclear who they will be and under what conditions they will operate. Leading opposition figures, who under ordinary circumstances would be running in the election, are either in jail or have been disqualified by the puppet National Electoral Council. With no guarantees of a free and fair voting process, the stage is set for a sham election and a political fiasco.

Oil and debt

What happens after the government steals the election? That depends entirely on the cohesion of the opposition coalition and the international community’s willingness to hold Maduro to account. Determined action by enough international actors could force the government to hold honest elections or step down peacefully.

There are several reasons why Venezuela matters geopolitically.

First, the country sits on the world’s largest oil reserves and significant portions of its annual production are committed long-term to China and Russia to repay billions of dollars in public debt.

China’s role in managing the country’s impending, $50 billion sovereign default will be crucial.

Second, China is Venezuela’s primary creditor, and its role in managing the country’s impending, massive sovereign default – involving over $50 billion in debt – will be crucial. For its part, Russia’s state-owned oil company Rosneft effectively owns almost 50 percent of Citgo, the U.S. refining and marketing arm of Venezuela’s national oil company PDVSA. How will Russia respond if Venezuela’s creditors ask a U.S. court to seize Citgo’s assets as collateral for their defaulted bonds?

Third, the Venezuelan elections in May will be a crucial test for Latin America’s new regional architecture, which has emerged as a new expression of collective agency to supplant the old pattern of U.S. hegemony. How the Lima Group, the Union of South American Nations (UNASUR), the Organization of American States (OAS), or the Community of Latin American and Caribbean States (CELAC) perform will have long-term implications for the future of multilateralism. Their ability to cooperate with international partners like the European Union, the UN and various NGOs will also be an important gauge of their influence.

Humanitarian crisis

Meanwhile, Venezuela continues to slide into the Western hemisphere’s most severe humanitarian crisis since the collapse of Haiti over a decade ago. Shortages of food and medicine affect thousands more every day. Inflation in 2017 was over 2,000 percent. The national poverty rate has increased from 48 percent of the population in 2014 to nearly 90 percent last year.

The worst part of the deepening crisis is that it disproportionately affects the young. Unemployment in the 18-24 age group is double the national average. The portion enrolled in secondary or higher education has dropped to just over 40 percent, from 50 percent a few years ago. Young people are also more likely to join the streams of refugees fleeing the country.

The idea of humanitarian aid as a means to deal with the broader crisis has gained traction in the EU and was brought up for debate in the UN by several Nordic countries, despite fierce opposition from Venezuela’s representative.

Regional response

Another proposal to force the Venezuelan government to accept some form of external humanitarian aid invokes the Responsibility to Protect, which in past decades played an important role in justifying intervention by the international community in Africa and the former Yugoslavia. This argument, put forward recently by GIS expert Emilio Cardenas, suggests that Venezuela’s humanitarian crisis and mass migration threatens the security of the region and therefore requires a regional response.

Professor Cardenas would operationalize his proposal by having all South American countries withdraw their representatives from Caracas and demand that the Maduro government allow some form of peaceful intervention to alleviate the suffering of the Venezuelan people.

It should be emphasized that all countries in the region – even members of the Lima Group and most of the political opposition in Venezuela or in exile – are firmly and passionately opposed to military intervention. U.S. President Donald Trump seems unaware of this overwhelming opposition or unmoved by it. One reason is that his policy on Venezuela is shaped by a coterie of Cuban-American politicians who see all of Latin America as an extension of their opposition to the Cuban regime. They see an attack on President Maduro as an attack on Raul Castro.

So far, the U.S. has imposed sanctions unilaterally on individuals in the Maduro government and has indicated that it will oppose efforts to use the country’s new cryptocurrency, the petro (short for petromoneda), in U.S. markets. Unilateral sanctions are unlikely to work; much more could be done if the U.S. were to reach out and negotiate some common ground with the Cardenas proposal for regional action.

Venezuelans are fleeing to other countries in staggering numbers, creating a regional crisis precisely of the sort that Professor Cardenas described. Until recently, most of the exodus was made up of the wealthy, the middle class and professionals. In the past year, however, they have been joined by the most desperate element of the population – the poor, the unemployed, or simply people fleeing the highest rates of violent crime in the world.

More than half a million Venezuelans fled to Colombia over the past year, with another 50,000 crossing the border into the northern Brazilian state of Roraima. Neither country is prepared to deal with such an influx. The refugee inflow has put the peace process in Colombia in serious peril, while Peru has issued temporary residency permits to nearly 250,000 Venezuelans. Tens of thousands have also fled to Guyana and the West Indian islands Aruba, Curacao, Trinidad and Tobago. In all, the total comes to well over a million migrants.

Fiscal squeeze

The economic collapse that underlies this exodus is manifest in the decline of the national petroleum industry. In February 2018, Venezuela’s oil output dropped to a 30-year low of 1.5 million bpd, while the rig count was at half its level of five years before. Falling oil production has restricted exports and led to a collapse in government revenue. By mismanaging the oil industry, Venezuela’s government essentially has applied sanctions on itself.

Venezuela is now in default on virtually its entire external debt. Government and PDVSA bonds have stopped trading or sell at pennies on the dollar, attracting speculators and so-called “vulture” funds. The alternative is debt restructuring, but no one wants to deal with the Maduro government.

The fiscal squeeze means Venezuela’s government has less largesse to dispense, even to its loyalists.

Venezuela’s fiscal squeeze means the semi-authoritarian government has less largesse to dispense, even to its loyalists. Crucially, this includes senior military officers, who until now have been stalwart in their support. It is reported that more and more of the high command have become involved in drug trafficking and profiteering from food and medicines imported under government aid programs. This situation will create dissension and increase defections from the Maduro camp. Corruption and internal friction will complicate any transition.

Distribution of food and medicine is increasingly being handled by military personnel, using the new national identification card, the Carnet de la Patria. This ID will also be used to validate voters in the coming elections, providing another handy weapon against the opposition.

Our man in Havana

Only international mediation between the government and the opposition offers hope of a nonviolent solution. Most Venezuelans want to vote and would prefer an orderly transition to a more efficient, democratic government. For this to happen, the MUD must resolve its internal differences and organize a massive turnout at the polls. It must also reach out to the rural population and the urban poor, who remain susceptible to Chavismo’s appeal. Over time, the MUD risks becoming a front for the country’s wealthy, mostly in exile, and for the surviving remnants of the urban middle class.

For their part, foreign states and NGOs must quickly assemble enough trained observers to monitor thousands of polling places. If the government cheats, the international community’s response will be a key litmus test. Its key assets are trusted mediators such as former Spanish Prime Minister Jose Luis Rodriguez Zapatero and the former president of the Dominican Republic, Lionel Fernandez.

Any successful mediation will require Cuba’s participation. Somewhere between 5,000 and 10,000 Cuban “advisors” remain in Venezuela, where they play an important role in the military and security forces. Just as Cuban President Raul Castro played a key role in building confidence between the Colombian government and the FARC guerrillas, paving the way for a peace agreement, Havana’s mediation could prove indispensable to a peaceful transition in Venezuela.

The Cubans need Venezuelan oil and could offer asylum to several key Maduro henchmen.

The Cubans need Venezuelan oil, and the opposition could easily guarantee supply at favorable rates under a new government. Cuba could also offer asylum to several key Maduro henchmen, who would otherwise face prosecution in the U.S. or Europe for drug trafficking and human rights violations.

Such mediation will not be simple. Raul Castro, after all, has little appreciation for the niceties of free elections. And Mr. Zapatero is resented by many in the opposition for encouraging them to accept the government’s proposal for early elections, even though the MUD’s minimum demands for freeing political prisoners and allowing election observers were rejected by the Maduro regime. These and other strong emotions must be mastered if Venezuela is to overcome its looming crisis.